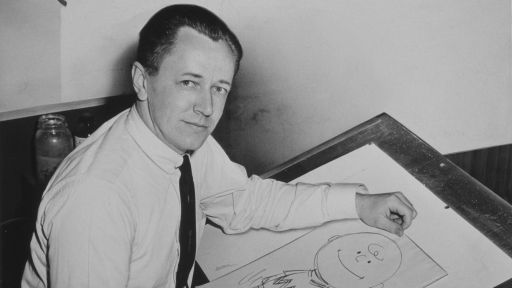

Like his famous subject, director David Van Taylor discovered the extraordinary in the ordinary while making AMERICAN MASTERS Good Ol’ Charles Schulz.

Like his famous subject, director David Van Taylor discovered the extraordinary in the ordinary while making AMERICAN MASTERS Good Ol’ Charles Schulz.

Q: What was the genesis of the project?

A: It actually started when I was home visiting my dad in Washington, D.C., a few years ago. I went down to the basement and poked around some boxes and there were all of my old Peanuts books from my childhood. I brought them home for my daughter, who was eight at the time, and she really got into them. I started thinking about Schulz. And then Ali Pomeroy, the producer, read a piece in the New Yorker by Jonathan Franzen, the guy who wrote The Corrections, which is a novel we both loved, all about a Midwestern family and its complex dynamics. I don’t even remember what his piece about Schulz said – it was something about his relationship to the comic strip growing up. But I put those two things together in my head – the strip I remembered from childhood, and this vision of complicated family dynamics, and I thought, there must be a story behind these comic strips, which are so unexpected and profound and serious in a way that comics aren’t generally, or weren’t at the time. Ali and I at first said, “Somebody must have made an in-depth documentary about Schulz’s life.” When we realized nobody had, we knew we were onto something.

Q: What did you know about Charles Schulz when you began?

A: I really knew nothing about him as a person. But I had had this relationship with Peanuts as a kid and so I just had a feeling. We looked at an A&E biography about him that basically pedaled the myth, which was his myth: “I’m not an interesting guy, I’m an ordinary guy.” He was an ordinary guy, but that doesn’t mean he wasn’t interesting. Everything that happened to him in his life and that he did – the drama of it was completely ordinary. It’s not sensational. The most bizarre kind of factoid, which we open the film with, is that here’s a guy who watched Citizen Kane 40 times. That’s fascinating in its own way. You don’t expect it. You wouldn’t expect it of the guy who drew Peanuts, and so it gets you started thinking.

Q: How long did it take you to be able to connect the biographic aspects of his life with the comics?

A: It took the entire time, really, to make those connections. Some images came pretty early on. When I started hearing about his first wife and learning about their relationship, I had this vision of Lucy and Schroeder at the piano, and Lucy essentially saying “Do piano players make a lot of money?” And that in the end was something that we pursued as a motif in the film. Other connections occurred along the way, as when Ali realized that the Thanksgiving special mirrored a story from the breakup of his first marriage.

But the number-one challenge through the editing of this was how do you make these connections? How do you integrate the work into the story of the life? The story of the life is the structure of the film. But how do you get the work in there? Especially in the 27 years of his life that happened before Peanuts? Which is an absolutely critical part of his life.

Q: Why was that so hard?

A: One of the challenges was that the drama of his childhood – it’s not the drama you would expect from Peanuts. Because it’s finally all about him and his mother, his relationship with his mother as an only child. And then his mother dies when he’s still quite young and about to be shipped off to military service. Peanuts, on the other hand, is a world that is not about the kids’ relations to the adult. The adults have been “disappeared” from that world. So it’s very difficult to figure out how to integrate the story of his life in that childhood period with the comic strip, which, in a way, was about something totally different. Literally, it was the day before we locked picture that we, Juliet Weber (the editor) and I figured out how to put Charlie Brown into the first act, the first 10 minutes of the film.

Q: How long did you research before you shot your first interview?

A: This is a film about a guy who had died four years before we started, and had been at an advanced age. Obviously, his contemporaries are also at an advanced age. In fact, we missed some of them because they had passed away by the time we started. So we felt it was very urgent to go out and film interviews on what American Masters called the “endangered list” as soon as possible. That was the first thing we did as soon as we could cobble together the first money. And that was research. To me, it’s really a back-and-forth process: on the one hand you want to go to the interviews with some focus and ideas, and on the other hand the interviews do tell you what your story is. They lead you and they hopefully open your eyes.

Q: Any good stories that you left out?

A: You could almost make a whole film about his relationship with “the little red-haired girl,” a character in the strip who is based on an actual woman. As a young adult before he sold Peanuts, Schulz fell in love with her and proposed marriage, and she broke his heart. In a way, that is what unleashed his creativity, that broken heart. And then, later in his life, when his first marriage is failing, he calls her up and spends these long hours reminiscing on the phone about their time together. She’s still married to the guy that she jilted him for, but on these phone calls she and Schulz are engaging in this fantasy, living in the past. It’s part of an overall trend where he delves more and more into the past as his life goes on. He’s trying to recreate the past in the strip and reenact the past, his childhood.

Ali did this fascinating interview with the real “little red-haired girl,” which left us with complicated feelings. On the one hand she is completely charming, which is why Schulz fell in love with her. On the other hand you can still see the flirt and the heartbreaker. To this day. But ultimately I come down on her side, in the sense that she was right – she made the right decision, for her, not to marry him. Even though he became richer than Croesus. Because she knew that he would always be a loner of sorts, and that they would not have the kind of open, easy, “ordinary” relationship that she wanted. And that’s what she has with her husband, a retired firefighter. They’re traveling all over the world, just got back from Norway. It’s very different from what you hear from Schulz’s wives. So she’s bearing a certain wisdom as well. But from his perspective, it was really a permanent heartbreak.

Q: Did Schulz continue to call her after this period of crisis in his first marriage?

A: They stayed in touch almost to the day he died. But he also kept trying to work through this primal heartbreak in other ways. Lynn Johnston, the For Better or For Worse cartoonist and a good friend of Schulz’s, told us a story that didn’t quite fit in the film. They were in Washington at a cartoon convention, and at some point Sparky just got overwhelmed by the autograph hounds and all the attention. So he grabbed her and they ran out of there, hopped in a cab and ended up going to the Vietnam Memorial and then strolling along the banks of the Potomac while the cherry blossoms were in bloom. At one point he turned to her and said, “What if we could turn back the clock, and we were working together at Art Instruction?” Art Instruction is the place where he met the real little red-haired girl. “What if we were young and it was 40 years ago? What do you think our relationship would be like?” Basically, he was trying to cast her as the little red-haired girl in his attempt to re-enact, and change, the past. And Lynn said, “Sparky, I would have been your competitor. I would have been right alongside you trying to get syndicated, and I would be trying to beat you out. I would have been a cartoonist.” She rejected that particular fantasy of his, and drew a boundary. And he basically got in a cab, left, and didn’t talk to her for a couple of years.

Q: How will the film alter the given perception of Charles Schulz?

A: This is not the film most people will be expecting about Charles Schulz. And I think it’s not the film many other directors would have made about Charles Schulz, for American Masters or anywhere else. This film is very much informed by my view of the world. But then, my view of the world was certainly influenced by Peanuts. And even as an eight-year-old kid, I never really thought Peanuts was all sweetness and light. Charlie Brown is like the Job of the comics page, and I think I connected with that from a very early age. And that has affected every film I’ve made. In some ways, I’m coming full circle by making a film about Peanuts and its creator.

Q: Tell us about the way in which you push the stylistic envelope in this film.

A: I don’t know that we pushed the envelope. We were looking for a style that was appropriate. I always believe in elegance – not in the sense of something fancy or beautiful, but the idea that you use only what you need to use. And in this case, we particularly felt it was appropriate because Peanuts is so elegant. The aesthetic miracle of Peanuts is that Schulz did so much with so little. And by minimalizing its style compared with most of what came before, he was able to free up this emotional content, as one of our interviewees says. He was extremely expressive with just how he drew Charlie Brown’s mouth in any given panel. So we felt it was appropriate to have a style that matched Schulz’s style in a way.

I’m always thrilled when I see a documentary that gives me a new aesthetic idea, whether it’s how somebody uses stills, or how they shoot a newspaper headline, or how they make cuts from one interview to another. It’s an expressive medium, and the more tools you have in your toolbox the better. But I have a firm notion that form should follow content. At the beginning of developing the film, someone always wants you to write in your proposal “What is the visual style going to be?” Really, I don’t even want to think about that. I need to figure out the story first and the style needs to follow from the story, or from an idea of what the film is really about. That’s my principle. When I see a film where it doesn’t feel like the style grew out of what the story was about, and instead it grew out of the director saying “Oh, let’s jazz this up,” I bristle.

Q: A lot of people call this the age of documentary. What do you think?

A: The first thing to say is that I have three children, one of whom is three months old, and I haven’t been out to a movie theater in a long time. So in some way I’m unqualified to comment because I’m just plain out of it. But I’ve been doing this for a while now, including 12 years at Lumiere Productions. I have this image of documentary makers as surfers. There’s all these waves going on and they just keep coming: whether it’s the advent of cable or the foundations being interested in social-issue documentaries, or whether it’s the Internet or reality TV, the marketplace keeps changing, the waves keep coming. And they’re different every time. For a filmmaker who wants a career, your job is just to stay up on the wave one way or another. You can’t get distracted by the swell of the wave. You have to think about where you’re going.

Q: How do you maneuver the world of marketing and funding?

A: It’s complicated. I had a film, A Perfect Candidate, that was an early part of this current wave of theatrical documentaries. But by now there are a lot of films jumping on this theatrical bandwagon. And I’m not sure they all belong there. Most of them are not going to make any money in theaters. There’s a certain glamour, but you’re not in every case serving the film. You can almost always get to a larger audience on television. A much larger audience. You really need to consider the needs, and the potential, of each film individually.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I have two more Lumiere films in post-production. One is called Advise and Dissent. It’s about the Supreme Court confirmation battles over Roberts, Miers and Alito and it’s really about the state of our democracy and what’s happening to justice in our land. It’s a vérité film and it’s not an easy one, let’s just put it that way. I’ve been working on it for a long time. And then there’s another long-term project called When Muppets Dream of Peace, about Sesame Workshop’s attempt to bring Israelis and Palestinians and Jordanians together to foster peace through children’s television. That’s going to be on PBS one of these days. So stay tuned – and don’t forget to check local listings.