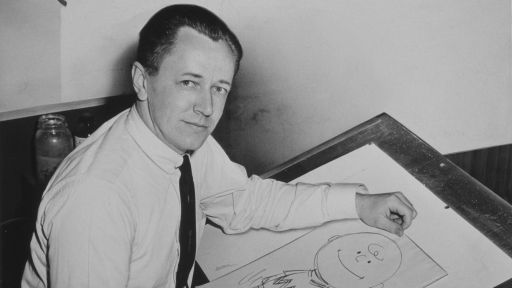

The following is excerpted from the biography Schulz and Peanuts by David Michaelis. In this passage, young Charles “Sparky” Schulz sets off to serve in World War II on the eve of his mother’s death.

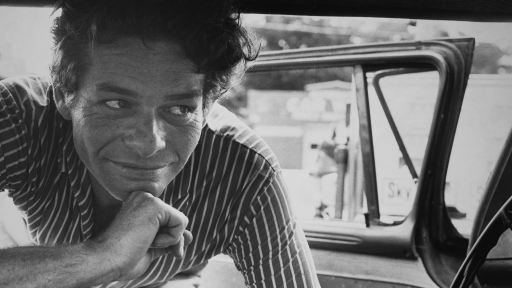

Chapter One: Sparky

The great troop train, a quarter-mile of olive green carriages, rolled out of the depot and into the storm. Nearly a foot of snow had fallen on the Northwest through the day, and now, in the short winter afternoon, the blizzard veiled the domed heights of the State Capitol in St. Paul and the pyramid-capped Foshay Tower, tallest building in Minneapolis. Snow curtained the Twin Cities from one another, blurring everyday distances. Only the railroad and streetcar tracks cut clear black lines into the mounting white cover.

In the Pullman, Sparky kept to himself. No one yet knew him. At roll call he had come after “Schaust” and before “Sciortino,” but except for his place in the company roster he seemed to have no connection to the men and, as one of his seatmates was to recall, “no interest in joining in any conversation,” not even about the weather. The snowflakes swirling at the Pullman windows only contributed to his impression that he had been thrown among “wild people.”

To his fellow recruits he presented himself as nondescript: simple, bland, unassuming-just another face in the crowd. With his regular looks, he passed for ordinary so easily that most people believed him when he insisted, as he did so often in later years, that he was a “nothing,” a “nobody,” an “uncomplicated man with ordinary interests,” although anyone who could attract attention to himself by being so sensitive and insecure had to be complicated.

Don Schaust, then seated alongside Schulz in the Pullman, later recalled that, as they rumbled across the Twin Cities, his seatmate remained silent, “very quiet, very low . . . deep in his own misery,” and how he had asked himself, “What’s the matter with this guy?”

No matter what the others said or did, Sparky sat watching the snow sweep up to and pull away from the window, giving no sign that he had just come through the worst days of his life.

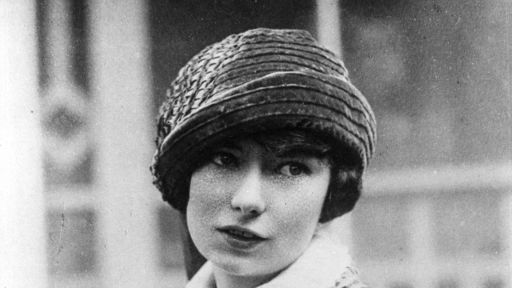

He would never discuss the actual kind of cancer that had struck his mother. Throughout his life, friends, business associates, and most of his relatives believed that Dena Schulz had been the victim of colorectal cancer. In fact, the primary site of his mother’s illness was the cervix, and she had been seriously ill since 1938. As early as his sophomore year in high school, Sparky had come home to a bedridden mother.

Some evenings she had been too ill to put food on the table; some nights he had been awakened by her cries of pain. But no one spoke directly about her affliction; only Sparky’s father and his mother’s trusted sister Marion knew its source, and they would not identify it as cancer in Sparky’s presence until after it had reached its fourth and final stage-in November 1942, the same month he was drafted.

On February 28, 1943, with a day pass from Fort Snelling, Sparky returned from his army barracks to his mother’s bedside, mounting the stairs to the second-floor apartment at the corner of Selby and North Snelling Avenues to which the Schulzes had moved so that his father, at work in his barbershop on Selby, and the druggist in his pharmacy around the corner, could race upstairs to administer morphine during the worst of Dena’s agonies.

That evening, before reporting back to barracks, Sparky went into his mother’s bedroom. She was turned away from him in her bed against the wall, opposite the windows that overlooked the street. He said he guessed it was time to go.

“Yes,” she said, “I suppose we should say good-bye.”

She turned her gaze as best she could. “Well,” she said, “good-bye, Sparky. We’ll probably never see each other again.”

Later he said, “I’ll never get over that scene as long as I live,” and indeed he could not, down to his own dying day. It was certainly the worst night of his life, the night of “my greatest tragedy”-which he repeatedly put into the terms of his passionate sense of unfulfillment that his mother “never had the opportunity to see me get anything published.”

He saw her always from a distance, and as the years went by, with each stoical retelling, the moment became more and more iconic. It was safely frozen in time-as puzzling a farewell in its quiet, coolheaded resolve as the lines spoken by the mother as she prepares to lose her son in Citizen Kane: “I’ve got his trunk all packed. I’ve had it packed for a week now.” Frequently, often publicly, Sparky laid out the terrible resigned pathos of what his mother had said to him that night. Only as he got older and experienced parenthood himself would he “understand the pain and fear she must have had, thinking about what was to become of me.”

The blizzard had brought everything to a halt. But the train drummed on across St. Paul, and landmarks familiar even in the snow slipped past his window, alerting him that his own neighborhood was approaching. Then there it was for all to see.

Mud-brown, two-storied brick buildings huddled along his snowbound street. From where the Great Northern Railway overpass crossed North Snelling he could see down to the Selby intersection two blocks to the south, where since Monday he had sleepwalked through funeral arrangements with his father in his family’s rented walk-up. Even before this week of calamities, he had considered this part of St. Paul the setting of “my most influential section of life as a child.”

Above the buildings to his right, a Greek-pedimented entrance marked the huge elementary school he had attended. He could see Dayton Avenue, a sidestreet among whose small, somber dwellings Carl and Dena had lived in 1921, during the first year of their marriage, and, next door, the roof under which his father had sheltered the family during the Great Depression, some of the lonelier years of Sparky’s childhood, and the scanty backyard where the kooky puppy Spike, living in his own world, had gobbled up some glass. There, on the corner of Selby and Snelling, was their streetcar stop, whence came, among his earliest memories, the image of himself getting aboard with his mother, a small boy on a stiff cane seat, off to the department stores…

HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2007.