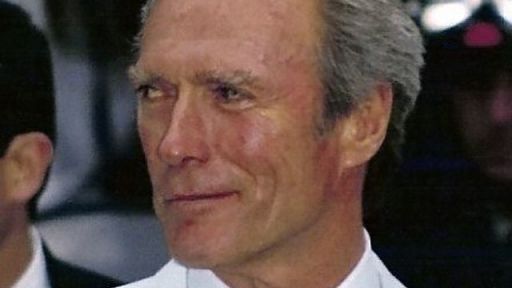

AMERICAN MASTERS interviewed “Clint Eastwood: Out of the Shadows” director Bruce Ricker and writer David Kehr to get their thoughts on Eastwood, documentary filmmaking and jazz.

AMERICAN MASTERS interviewed “Clint Eastwood: Out of the Shadows” director Bruce Ricker and writer David Kehr to get their thoughts on Eastwood, documentary filmmaking and jazz.

Q: What got both of you interested in this project?

Kehr: Take it Bruce…you got interested first.

Bruce: I’ve been working on and off with Clint Eastwood since 1987, on different music projects and some of his feature films. And at some point, oh, I guess about a year-and-a-half ago I had a conversation with Susan Lacy. She was always interested in doing Clint Eastwood as an American Master. I asked Clint if he would be interested, and he said ‘yes.’ So I knew at that point, that if we were going to do it right, I had to surround myself with people who had dealt with Clint over the years. So, I got Mary Lea Bandy, who had the Museum of Modern Art film archive, and Jeanine Basinger, who had Clint’s personal archive at Wesleyan University. And discussing everything with Mary Lea, we realized that Dave Kehr was available. I had met Dave over the years through Pierre Rissiant, and we had always talked about Clint, and Dave had been reviewing Clint’s films for a long time. So we thought that Dave would be a good person to be the writer and give a sense of discipline to the approach of the film. Then Dave came up with a long treatment for the film touching upon the things that we would deal with about Clint, essentially dealing with Eastwood’s cinematic career.

DK: When I first got interested in the project was when Bruce called me up and I said, “sure, I’m interested.” It sounded like a great opportunity to work with the two people I really respect, Bruce and Clint at the same time. I never had any experience writing this sort of thing, so it was a real education doing it…and, hope we can do it again someday.

Q: If I can follow up with one of our favorite questions…When did you become aware that Clint Eastwood existed?

DK: When I was a gangly, painfully shy thirteen-year-old seeing A Fistful of Dollars in some crummy theatre in suburban Chicago. And, you know, like everyone else in the country, he just seemed a pretty good role model for a (laughs) painfully shy, gawky thirteen year old, and you know, Clint is part of my subconscious ever since, I think.

Q: Did either of you learn anything that surprised you about the subject, Clint Eastwood, while making this film?

BR: I guess the thing that kind of emerges about the whole thing is how Clint really knows a lot more about film history than one realizes; he could draw upon it, and doesn’t get bored. We kept trying to bring Jimmy Cagney into it or things like that. He sort of enjoys the irony and juxtaposition of how he would be represented, and what Dave or my insights could be about Clint’s persona or his pursuit of his career. The key is that throughout the film, we tried to keep respecting his ambition about how he wanted to deal with his life, and also we allowed him to acknowledge his own mythology, how he decides to figure out how he became this sort of mythic figure.

And then the third thing, which happened obliquely, was, that a person is allowed their own life. We can’t impose meaning upon someone’s life afterwards. So we purposely decided not to summarize what Clint means to everybody, and what the films mean.

DK: Well, I hope the surprise that the film puts over is that he’s not an actor who directs, he’s a director who acts. His real interest is in filmmaking, and in telling stories, and in working with the camera, and working with actors, and working with his crew, and that’s when he really seems to come alive. It’s, I think it’s the most important thing in his life.

Q: Are there any interesting anecdotes about the filming or, interviewees…?

BR: I think what, what was interesting was how people like Forest Whitaker, and even Martin Scorsese really wanted to be in the film, and they kept on putting it off and putting off, and it was amazing how everybody that we wanted to be in the film suddenly found a way to be interviewed. I think it’s partially, there is a certain sense of, respect for Clint as a filmmaker, or as a presence in American movies that everybody sort of gravitates to, from Donald Sutherland to James Garner to Meryl Streep.

Q: Could you describe the production process, anything about how you chose to shoot the film, or any additional interviews you picked up along the way, and why you picked them up, or staffing on production, or the editing process?

BR: Essentially, what I tried to do is make the film, almost like the pacing of what a Clint Eastwood film would be like. So we tried to have the interviews sort of, darkish, you know, like Bruce Surtes, so it, would be darker than usual, and lots of widescreen. And also, have sort of a certain quiet pacing to it. Because one of the key things, which we avoided, was the conventional wisdom, to have interviewee engines to carry the story, with a certain amount of energy. Eastwood creates his own laconic energy, which you have to let it be. So, the key is to respect Clint’s own flow of energy and his own creativity, but figure out a way that you could actually incorporate, what he’s trying to say, and do it on our own, but also make sure that you can’t tell who made the film. And David’s narration is oblique; it doesn’t create a false sense of intimacy that we really know about Clint. We’re not really trying, even with the narration, trying to say we know what the answer is to Clint’s success, or why he does these things, or why the films work. You know, the, the advantage also was that, since Clint trusted us, we were able to get all the footage, which meant that we could use his work to illustrate the film, instead of come up with our own narrative theories about it, which always are not right anyway.

DK: I think that’s the great advantage of making a film, rather than writing a review, is that you are able to quote so extensively. And we’re very lucky in that Clint still has so many friends in the industry, that everything we wanted we were able to get to illustrate the development of his career. And it’s a unique opportunity, and very nice to have it.

Q: Were there any problems along the way with the production that you had to deal with?

BR: I think that the problems were only aesthetic; how do you, put all this morass of material into a narrative flow. And also, try not to deal with anything personal, which is not relevant to the real story. There’s always people who want certain types of material, and their Oprah Winfrey-type of insights, a little bit of scandal, or summing up all the time. So the key was to create some sort of interest in Clint’s life and career without resorting to vicarious ways of promoting interest in people’s lives. So, that was a challenge, and also, I think, the real challenge.

DK: Yes, Clint is somebody who doesn’t discuss his private life, at all, except through the distance of his films. And, all of his movies are incredibly personal, they are all dealing with things that are going on inside of him, but you won’t get him to articulate that, you have to examine the movies. And I hope what our film does is relate his films to moments in his life, to suggest where some of these images and ideas came from without forcing a biographical reading on the films. And, I hope, suggest, too, how the movies have allowed him to understand himself better, and live his life as a man.

BR: Well, you know, I guess, in a way it’s him coming to terms with his own design for life. And I think he’s surprised as we are that he’s accomplished so much. Ultimately what happens is, with this particular documentary, people go back, and now everybody wants to see Outlaw Josey Wales, Dirty Harry, and Beguiled again. So, I think it worked out to be a pleasant surprise that everything we wanted we got, including Morgan Freeman with the narration, and original music. The film is a sense of discovery. More so for the audience than I think for Dave and myself.

Q: Why do you choose American Masters for this, or do you think American Masters is the right place for this story to be told?

BR: Well, Clint is an American Master, I mean, within the definition of the series, because he is a good prototype of American culture. You might not say high culture, pre se but certainly at the level of Roy Lichenstein. It’s also the only block of time in network television that you could actually run something straight, ninety minutes, no commercials. And there is the certain cache to American Masters that has built up through the years, through Leonard Bernstein, et al.

DK: Yeah, I think he’s a, classic American artist in that he doesn’t promote himself, self-consciously, as an artist. And, like so many of our great filmmakers, he’s never gone out looking for recognition, and he hasn’t really received it, until in the very end of his career, with the Oscar for Unforgiven. He’s not a self-promoter, and neither was John Ford, and neither was Howard Hawks, and these are people you look back on now, and they seem like giants in the field, and I’m sure that Clint will come to see the same way.

BR: And he does come out of the American literature thing, of Hemingway’s sense of sparseness, and Steinbeck’s sense of populism, and with American culture, films have supplanted American novels at this point. What William Goldman said was that most people today rather than try to write the great American novel, they want to be the next great American film director, so Clint in a way is compared to Faulkner, Hemingway, or Fitzgerald. Not that he would ever become a great novelist, I doubt that, but the delivery of culture in this country is changed, so Clint just seemed to be in the right time and right place, but also, Clint had the sense of awareness about jazz being a very important American art form. And being in awe of Charlie Parker, and Coleman Hawkins, and Lester Young, when he’s sixteen; they were people Jackson Pollock, and Kerouac, and Dekoonik, were also interested in those type of people back in the forties, so he comes out of that whole era. As what Scorsese said, he’s an artist after the atomic war so he does fit in with be-bop and the beat generation, and existentialism.

Q: and Camus

DK: and Camus, let us not forget.

BR: Camus and The Stranger.

Q: Could you describe your background credits?

DK: Well, I’ve been a movie critic for my entire adult life. If that can be granted to be an adult life. Started at the weekly in Chicago, went to the Chicago Tribune for a number of years, went to the New York Daily News for a number of years, and now I’m largely free-lancing. I worked for an internet site called citysearch.com, and do a comp at the New York Times. And that’s about it right now.

BR: I got my bachelor’s, my college degree in American studies back in the early 60’s, which meant that you could just read about anything to do with American culture; theatre, or literature and stuff. And then I went to law school because I didn’t know what to do, and then I eventually decided to make a film about jazz musicians, and then I thought I’d switch careers, but it wasn’t that easy, and it took twenty years to keep on making, documentaries, and the jazz connection is what got me to Clint Eastwood, which got me to a higher access to Hollywood in a very indirect way. And as somebody pointed out to me, um, the way Hollywood works, you could have one, you could only work for one king at a time. And I guess, I got lucky, I guess, my Chinese warlord was Clint Eastwood who loved jazz, and so over the years, we sort of got to know each other. But to get back to why the film works partially is because both Dave and I are raised as Lutherans, which creates a moral stance about things. And the one thing that Clint does bring out is a sense of morality, but you’re not hit over the head with it. Or like Scorsese says, he doesn’t cop out at the end so. What we tried to do with the film is try to create this sort of moral stance with a sense of sparse aesthetics. And that’s why the Giacometti quote works out well.

DK: Magnificent, can’t improve on that.

Q: So, how do you feel your backgrounds came together on this, as how much of this is a jazz film, and how much of this is a film essay?

BR: Oh, I think it is more of a film essay than a jazz film, but it is more of a cultural essay. I mean you’re using film as the medium, but then you’re using a whole sense of understanding. The one thing about people who are interested in jazz for the most part are highly culturally ambitious, it isn’t a sort of an art form that attracts indifferent people. Clint is a challenge in a way because people don’t take him for somebody who is really intelligent, and smart, and in control of his life. But Clint as a student has always surrounded himself with intelligent people. So, subliminally, you know, he chose us, in a way, because we never flaunted our sense of…(laughs)…our fandom about Clint, we always kept our distance.

Q: I guess the last question, what do you think Clint should do now, should he go on and do the Gabby Hayes roles, any advice for him?

DK: He seems to be doing just fine without my advice. As long as he can act and wants to do it, he should do it. And as long he can direct and wants to do it, he should do that too. I suspect he’s going to want to do one of both of those things for quite a while yet.

BR: Well, my sense of it is, that’s one of the reasons why we ended the film with him directing, I think he’ll keep on directing. I think he alludes to it, there’s a documentary about John Huston making The Dead on an oxygen tank, and Clint would certainly do that. The acting part, he could probably do that up to a point, but it might get a little boring at this point. But who knows, I mean, one would never try to predict what he is going to do next.

Q: Anything else you like to add?

BR: In hindsight, it looks like the whole project went pretty easy, and it probably did.

DK: Well, I think we got really lucky to have Clint Eastwood as the subject because the degree of cooperation was just incredible from him, and everybody else, so thank you Mr. Eastwood.