TRANSCRIPT

- Hi, I'm Clive Gillinson the executive artistic director of Carnegie Hall.

And it's wonderful to welcome you to this very special virtual event.

Celebrating the national broadcast of Marian Anderson, The whole world in her hands on the American Master series on PBS.

Marian Anderson had a more than 70 year association with Carnegie Hall.

She made her Carnegie Hall debut in 1920, presented her first Carnegie Hall recital in 1928 and performed for the last time in New York on Carnegie Hall's stage at her farewell recital in 1965.

She later made a small number of speaking appearances.

Her last one was in 1989.

All told she appeared at the hall 57 times.

In 1960 at the invitation of Isaac Stern.

She became one of the original board members of the Carnegie Hall Corporation.

When the hall was saved from demolition, she remained on the board until her death in 1993, on the occasion of the hundred 125th anniversary of Marian Anderson's birth, we could not be happier that this wonderful documentary film will appear on the American Master series.

She was most certainly that.

The film would not have been possible without the vision of it's director, Rita Coburn and the generous support of many funders who recognized the importance of this project, including the Better Angel Society, two of whose members, are Carnegie Hall trustees, Mercedes T. Bass, and the chairman of the Carnegie Hall board, Robert F. Smith.

We're very grateful for WNET's gracious invitation to join them in this special virtual event.

- [Woman] She was the first African American to make her debut at the Metropolitan Opera.

- [Woman 2] She was pursued by nobility and aristocracy.

She enjoyed the life of a diva.

- [Man] Marian Anderson was the first African American artist to be signed by RCA, Victor.

- [Man 2] She was performing in Europe for Kings and Queens, and she would come back home to her own country and have to sit at the back of the train.

In response, you stood flatfooted and she sang.

- [Man 3] Easter Sunday, April 9th, 1939.

- [Woman 3] There was a multitude such in your wildest imagination.

- [Woman 4] Even though we may not be able to articulate why that person's voice moves us so much because it's speaking to so many different parts of who we are.

That's what her voice had, this incredible power in it to stop a nation.

- Hello, I'm Michael Canter, executive producer of American Masters, which is produced here in New York for the WNET Group.

In advance of tomorrow's broadcast premier of American Masters, Marian Anderson: The Whole World in Her Hands.

I wanna welcome you to tonight's Zoom a event.

We're delighted to be recognizing this pioneering artist as we begin black history month.

Before we hear from our fantastic panel, I wanna thank the public television viewers like you, who help us at American Masters produce the kind of quality program which this series is known for.

And to all the supporters of Carnegie Hall and the Better Angel Society.

We're deeply grateful to all of you as well.

Here's a quick look at those who made this program possible.

- [Announcer] Support for American Masters provided by.

Support for this program provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, bringing you the stories that define us.

- Tonight's event was made possible by the extremely generous support of Robert F. Smith chairman of the board of Carnegie Hall and Mercedes Bass vice chair of Carnegie Hall.

And we want to give a very special thanks to them.

Now, tonight, I'm pleased to welcome director Rita Coburn celebrated mezzo-soprano, Denyce Graves and legendary tenor, George Shirley.

Rita Coburn is a Peabody and Emmy Award-winning director, writer and producer of radio, television, and film.

Beginning her career as a producer and writer for various news outlets across the U.S.

Rita went on to produce for the likes of the Oprah Winfrey Show, Oprah radio, Apollo Live, and Walt Disney Productions.

Her work aims to bridge the gap between generations and preserves African American history.

Denyce, mezzo-soprano, Denyce Graves has performed all over the world in opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, The Royal Opera, Opera National de Paris and the Vienna State Opera among many others.

She's become particularly well known for her portrayals of the title roles in Carmen and Sampson and Delilah.

George Shirley was the first African American tenor and only the second African American male to sing leading roles with the Metropolitan Opera, where he remained for 11 years.

His career span nearly 50 years, and he's won international acclaim for his performances in the world's greatest opera houses, including the Met, The Royal Opera, l'Opera de Monte-Carlo and of course, many, many more, he's in demand nationally and internationally as a performer, teacher and lecturer.

So welcome all.

And let's first start with a clip from the film where we'll all hear Marian Anderson speaking voice.

This is one of the great pleasures of the film to hear directly from Marian Anderson herself.

So please enjoy a section on how important the church was to her musical education.

- [George] The church was the epicenter.

We went to church for dinners.

We went to church for social events.

We went to church for religious services.

Sunday was an all day affair.

- [Marian] At six years old, we were taken to the children's choir with my aunt after a short while the group was singing so well that we sang for The Big Thunder School.

By the time we arrived at our little house, the director of the choir had already been there and left.

My mother told my father that Mr. Robinson wanted to be sure that I would be able to be in church earlier the next Sunday, because there were going to be visitors and he wanted that we should sing.

My father said in reply to that.

'I'm not going to have them singing my child to death', my first public appearance.

- So Rita tell us about these voice recordings that you found of Marian Anderson and what surprised you when you heard them.

- Well as a documentarian, you chase the story until it chases you.

And so I went to the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center that houses, the Marian Anderson archives, over 6,000 letters, 4,000 photographs.

And they had just compiled 34 real to real tapes.

They hadn't been there before.

So my spirit said since they are there, listen, I listened to all 34 transcribed them.

And what I was most excited about was that unlike anything I had heard or seen before, we were going to be able to call a documentary that would have her own voice saying how she felt about her life.

And so the agency that she had as a person, the renaissance woman, that she was from 1897 being born, to forwarding her career.

I wanted to hear from her.

And I thought that other people would want to hear from her as well.

Deep belly laughs her opinions on how she felt about things.

I thought that was important to bring to this documentary.

- Thanks. Well, George, you actually apparently met Marian Anderson in the hall of a library where you were working as a student and then had the chance to interview her rather for a radio program.

What did you learn from interviewing her and why do you think she's a pioneer in the world of classical music?

- Well, I think it's really a apparent that she was a pioneer.

She was one of the very first to be accepted worldwide as a major artist.

From her interview, I learned more about her life.

It was exciting to be sitting and talking to this woman, asking her questions.

This was at the WQXR Film in New York City.

I met her first as. I was a page at one of the local libraries in Detroit.

And one of the sororities gave her a tea.

They hosted a tea for her.

And there was a moment when she was standing by herself and I pushed my truckload of books up and handed her one of these little notes that people would sign and asked for books, and she smiled and signed it.

And I have that in my possession today, but she was a legend listening to her as a child on the radio to think that I would ever meet her, was a dream come true.

So yes, she was.

She always spoke of herself as a we, we will do this, we will do that.

And that was not just humility, but she was absolutely correct in that because we are all everyone that has preceded us, we are given genes from our ancestors.

So we are not just one person. We are many.

So she was absolutely on target with that.

She was modest.

She was a quiet force of love.

And that's what you hear whenever she opens her mouth to sing and to speak, her voice goes right to the core of your soul.

That's what made her special, that magnificent voice.

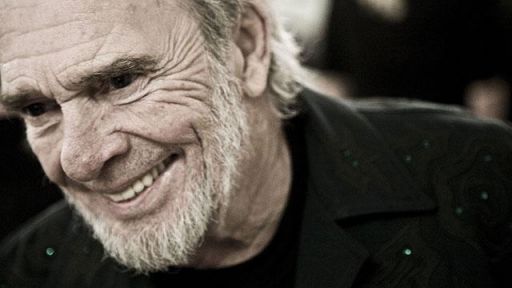

She was built like a singer looking at that face, those cheekbones, the structure and the sound that came out is forever with us.

Those of us who heard her from childhood and for me having the honor of sitting with this woman of meeting her the last time I saw her was at the Mets 100th anniversary.

She was in a wheelchair and I went over during one of the breaks and spoke with her briefly.

The smile was there.

She was a magnet in so many ways.

And again, it was a blessing to get to know more of her, from her.

And I'm grateful for that always will be.

- Thank you.

Well, Denyce, this first segment was about her experience growing up in the church, you actually created a program called 'Church' that involved Dr. Maya Angelo, among others.

For me, Marian Anderson truly seems like a saintly person and you got to know her.

What were your impressions of her as a person?

- Well, thank you so much.

And I love everything that Dr. Shirley just said, I'm not sure that I got to know her as it were.

I was kind enough to, she was kind enough to invite me to her home in Danbury, Connecticut.

I was, I can't remember.

It must have been 92 was one of the winners of the Marian Anderson Award.

And part of that award meant giving a concert at Charles Ive Center in Danbury.

And she was kind enough to invite me twice to her home to be in her presence, to talk with her.

But one of the things that was incredibly striking to me about her is that, and perhaps she had spent so much of her life time talking about the famous concert in 1939.

She didn't wanna talk about herself.

She didn't wanna talk about her career.

She was more interested in sharing the work that she was doing with the salvation army and the work that she was doing with children.

And she wanted to know what I was doing and what was going on.

And the day that I visited her, her nursemaid told me, said, oh my goodness, had you been here five minutes earlier, Kathleen Battle just left.

And so I was so happy to know that there was this community of supporters and those for whom she trail blazed and laid this path for were coming to surround her and letting her know how much we honor her and appreciate her and all that she's done.

So I wouldn't say that I really got to know her, but I did have the great, great, great fortune of being in her presence of speaking with her.

And she did give me some very precious things.

I mean, besides that moment, but she gave me a wonderful, a beautiful gown and let me into her closet.

And we were able to be sort of girls together and tell, oh, look at this and look at that one.

And that was incredible.

And I wore that only a few times.

And since that time have donated it to the Smithsonian Museum, but when we did the reenactment of her concert at the Lincoln Memorial, I wore the gown then.

- Wow.

- So it was just, it was an extraordinary, and I feel the same way that Dr. Shirley feels, I just could not even believe the fortune to sit across from this legend.

And I remember in the fourth grade, you know, when it was black history week learning about Marian Anderson and Jess, I could not believe that I was face to face with this incredible legend and this just regal presence.

It was amazing.

- Well, she may have ultimately tired of talking about that important concert in 1939, but it's a centerpiece of any American history and Rita Coburn's extraordinary film covers the full scope of Marian Anderson's life, including when she performed for the composer, Sibelius in Finland, who said, my roof is too low for you before calling for champagne.

Here in the U.S.

I think she consecrated the Lincoln Memorial as the place for our country to come together to consider important issues of social justice and a little historical background on that concert.

That's in the film, even though Marian Anderson had first sung at Carnegie Hall in 1920 and performed all over the world.

In 1939, there were plans to present her in concert in the Washington DC area.

And the first plan was for her to sing at Howard University, but their hall was too small.

And then they reached out to an all white, central high school auditorium.

They said, no.

And then famously the DAR Constitution Hall was approached.

And the daughters of the American revolution turned her down as well.

And ultimately with Eleanor Roosevelt's support, she gave this landmark performance in front of a crowd of 75,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial.

So here's a clip from our film featuring the late great actor, Ossie Davis, remembering that day.

- [Ossie] So I was one of the student body surrounded by 75,000 people standing out there that cloudy day.

Marian Anderson was the first one who made me realize that through art and music, she could reach inside me and just lift me from all that negativity and make me something else.

That Sunday will live forever.

(Marian sings) - Denyce, you mentioned singing in tribute to Marian Anderson in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

How would you describe Marian Anderson's courage and bravery in terms of that performance and what it was like for you to stand in front of that statue and perform?

- Oh, I don't know that I would be able to speak to what the experience was like for her, but I could share that after 9/11, I was invited to the National Cathedral.

I'm born and raised in Washington DC.

In a service that was a response to what had happened at 9/11.

And that was not unusual for me because I live in Washington DC, and I have a relationship with Washington National Cathedral.

And so sometimes over the years and during the career, if there was a dedication of a window, if there was a special service, they would ask me to come and perform.

And so I did, but as I stood there for the performance that I did at Washington National Cathedral, I looked in the audience and I saw President George W. Bush.

And I saw President Clinton and I saw president Carter And I looked, and I saw all of these incredible, there were five sitting presidents there.

And I said to myself in that moment, I wonder if this is how Marian Anderson felt when she was in front.

That's the thought that I had, I don't know.

I mean, you know, Dr. Shirley spoke earlier about the fact that she always used 'we', reminded of that famous phrase of Maya Angelou 'That I come as one, but I stand as 10,000'. And I think that a lot of African Americans certainly know this.

I was certainly taught this and I'm sure that probably was the case for Rita and Dr. Shirley as well, that whenever we were out in the public, we were representing the entire race.

And so, you know, we always had to really be aware of our behavior and how we carried ourselves out in public.

And so I'm sure that there was that weight and also pride at the same time that she must have felt.

- Rita.

This performance is just one of so many major performances that Marian Anderson gives around the world.

The film is subtitled.

She's got the whole world in her hands.

Tell us about her experiences outside of the U.S.

- I think that her experiences outside of the U.S, which preceded 1939, along with her family, her community and church is where Marian Anderson was actually made.

She had more opportunities in Europe, as Denyce says in the film, Europe did not have the stain that was present in America in enslaving people.

So they could hear her, not that it was a perfect place, but they could hear her for who and what she was.

And it is the birth birthplace of Mozart and the whole classical music recitalist genre.

And so she stepped off of a boat in London and stayed at the house of John Payne, a famous black baritone.

And she began to learn there. She went on to Paris.

She went on and met Sabellius and Finland and the Nordic countries, which we don't often think of.

When we say Europe, to be honest, they embraced her more than anyone.

And she began to flourish there.

And at the time when the Salzburg Festival was the concert of the world, she was invited to that concert.

And when she got ready to go, because of the rising fascism, she was dis-invited, the Archbishop of Salsburg, who was like the ministry of music, invited her.

And when she was dis-invited, they found a side stage and she had the courage and the presence to say, I'm going anyway.

There might be danger in Brooklyn, but this is in Midtown Manhattan and I'm going.

And so she went and she performed, and always, she performed her spirituals as well as her classical music.

And had she not had the agency to go, the shrewdness, the businesswoman, the entrepreneur, then she would not have met Tuscanini in her dressing room at the intermission.

And he coined that phrase that everyone now knows.

That Sol Hurok used to catapult her which was a voice like yours is heard only once in a hundred years.

And she took off.

But at every moment, Marian Anderson had the courage from her faith and her family roots to defy what the normal construct was of the society and do what she thought was best.

- Well, George, you performed on these major stages and helped to desegregate the opera world.

Tell us what your sense was of how Marian Anderson did that.

Both here in the U.S and overseas.

- Marian Anderson was born with courage throughout her psyche and soma.

For anyone to be able to stand in the midst of hatred, not knowing what might come flying at you from the crowd or wherever, stand up and be yourself, that takes tremendous courage.

And it takes a faith that you were born to do this, and that prayerfully you'll be able to do it on this occasion and be able to walk off stage.

I'm reminded of man who really gave Marian Anderson her first exposure in Philadelphia, the black tenor Roland Hayes who invited her to sing on one of his recitals.

Hayes did run into violence in the south.

After having been accepted in Europe prior to Marian Anderson's going, having been accepted in a very special moment.

When he made his debut in Germany, he walked out on stage to 'boos' and he stood there for 15 minutes or so until they got tired of booing and he started singing.

He changed his program to the, Schubert, 'Du Bist Die Ruh' which means you are rest you are repose.

And at the end of that recital, you got outstanding ovation, that kind of courage, to be able to open your mouth.

You know, the throat is something that reacts to fear to anger, but he was able to capture that audience that was initially anti his being on that stage and move them to a point of getting on their feet.

So that kind of courage was present in Marian Anderson.

It was present in all of those pioneers, Marian Anderson, Paul Robson, Roland Hayes, in our house were heroes because of their courage.

And also Joe Lewis, believe it or not, who I understand at one point studied violin, which I think probably added to the power of his right hand.

There was some music in his background.

So this kind of courage is inborn.

It cannot be put into anyone by society.

It is, you're born with it.

It may take you some time to find it.

If it is there, if it's not there, no one can get it, put it into you.

You know, we who teach, I can't put a singing voice into someone.

If it's not in there already, I can help them to uncover it, to discover it.

And Marian Anderson was born with it.

She was born with that voice as she was born with that soul that knew where her power came from.

So she was meant to be who she was and to do what she did.

She was handed a script when she was conceived, it was all written out.

It was all written out. She didn't make it.

She didn't ask to be born, but she was born.

And she was gifted at that time with everything that made her, the woman and the icon that she was and is, and always will be.

- Wow, thank you.

Our next clip speaks to Marian Anderson's incredible range and her billing as a contralto.

This was a kind of a revelation to me as someone who doesn't live in work in the world of classical music.

So take a look at this next clip.

And then we'll talk about that.

- Although she had a three octave range, she sang in the contralto mode.

- Contralto being the lowest possible female voice.

She could sing that to break your heart into a million pieces, but she also had a great top.

She had a great high C and her voice could live above the staff.

Meaning in soprano territory.

- [Marian] I don't feel that the singing a high C was any trouble at all.

To me, it was a larc.

One did not confine herself to being either soprano or contralto or anything else, but one was billed as a contralto.

- In the operatic world.

The Sopranos always are the leading ladies.

I've sung some of Marian Anderson's pieces and they were out of my tesitura meaning they were out of my range and my voice is classified as a higher voice than hers.

It's one of the reasons that I believe that Marian Anderson was not classified as a soprano is because that would mean that she would be the love interest of a white counterpart, which was not accepted at all at the time.

- So Denyce, you spoke so eloquently about how that classification denied her roles.

Could you just expand a little bit on that and how, you know, you're being a mezzo-soprano allows you to do certain things and what she was able to do and how miraculous that was?

- Well, I think that one of the things that we just heard from Marian Anderson herself saying one did not classify themselves as being a mezzo or contralto soprano, once you sang.

And I think we saw that we see that a lot throughout, sometimes throughout the career where we look at the late great Jesse Norman, who sang as a mezzo and then a soprano and Shirley Verette did the same thing.

Dr. Shirley knows him very well saying as a mezzo singer, as a soprano singer as a mezzo and even a lot of the golden age voices, people sang what was comfortable for their instruments.

But when we did the reenactment of the concert at the Lincoln Memorial, some years ago, back in the early nineties, I was asked to, I was given the great honor of singing everything that was sung on the concert, in the keys that was written in.

And I said, wait a minute, you guys wait a minute, this is high. Can we lower this?

And they said, no, we want this exactly in the same keys.

And I said, but come on.

Nobody's gonna know.

I mean, if we lower it like a third, who's gonna know, and they said, Denyce, we want it to be exactly the way that Marian And... and I said, this is a really high tesatura, meaning that it's sitting in an area that for me was not comfortable, right.

Meant a lot of, you know, work.

And I said, wow.

And that was what got me thinking.

I thought, gee, if she chose this repertoire, and if she chose these keys, that's very curious, because as I said, you know, in the film, I'm considered to be a mezzo-soprano, which a medium soprano or middle soprano or half soprano, the sopranos, like to hear that part half soprano.

But anyway, so that's where my voice is.

And it's classified higher than contralto, which is the lower female voice.

And I just started thinking when we did that, I thought, hmm, I wonder.

And then I started listening to her, seeing more and seeing more operatic repertoire.

And there was a tremendous amount of brilliance.

I mean, she had a really long voice.

And for those who know, you know, the black church, you know, you sing, whatever part is needed, right.

Sometimes you sing tenor, right?

Sometimes you sing bass, my mother and my aunt, they all sang tenor, you know?

And so I think that really developed a lot in the church.

People developed their full ranges.

And that may have been the case.

I think that when Marian Anderson sang, when Marian sang, that's the name of the book, isn't it?

When Marian sang that when she sang in the middle part and the lower part, it was so extraordinary.

And not anything that people had been used to hearing, certainly from a woman that kind of texture, that kind of richness and the fullness and the strength that that was absolutely anchored in that middle and the lower part, they just said, this is a contralto.

This is a contralto voice because that part of her voice was so incredibly interesting and extraordinary, but actually the whole voice was extraordinary. I think.

- Well, I think actually let me ask my colleagues to pull up a photo of you in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

I'm pretty sure this is a photo that represents that's now is that gown.

The one that Mar... - That's her gown.

That's a Karinska gown.

It had her name in it, Anderson in the back of the dress, just like you see in the opera house, but that was the gown that she gave me.

- Wow. And that's at the Smithsonian.

- It's now at the Smithsonian.

- Wow. Well, Rita, perhaps you could speak to, I didn't realize how important, you know, the way Marian Anderson presented herself and the gowns and the approach she brought to it.

And in your film, I saw a fabric become gown.

And so on, speak to what, what her presentation, how important that was.

- You know, when Marian Anderson was young, a lot of people thought that she was impoverished.

She was poor. She was not impoverished.

Her family, her mother sewed.

And so she said herself, we had proper clothing and so on, but she loved fashion.

The first dress she bought was 79 cents.

And she was so happy to see an advertisement in the paper after she had purchased it, that it meant to her.

She had some style, she had some forethought.

Gowns, and dresses became very, very important to her at the Marian Anderson museum in Philadelphia, that Jillian Petel runs.

They change the gowns all the time and show you these gowns.

There was a point at which in one of her books, she bought a gown that was 8,000 dollars.

And back in the day, that was a lot of money.

And she said, and it was worth every penny.

She understood her look.

She also said that when she went south, she at first didn't think she should gussy up so much, but she said it made the people stand proud that they saw what she meant.

And whether you call it swag today, or whatever you call it in the African American community, it was very important to dress properly, to show yourself capable of that.

Whether you had to sew or buy or wash it out at night, you should be dressed appropriately.

And I think that she took that to another level from the shoes.

You can see Sandra Grimes, her niece has a number of her pieces ruching on the sleeves.

And many of it the works were then made for her.

And I think that she loved it. And when we say diva, we don't mean the way that it's said today with anything negative to it.

But she lived the life of a person who could do that.

She was making 4 million dollars, after 1939 a year.

So she could do this and she wasn't pompous with it, but she knew what it meant.

And she dressed well and loved it.

- George, did you have that experience similar to what Rita pointed out for Marian Anderson of touring in the south and it being a sort of hostile environment?

- Oh yeah.

I mean, there was no way of not running into that kind of thing because it was there.

I mean, my first Metropolitan Opera Tour, 1962, it was interesting.

I've always said that doors are opened by people on the inside when they recognize that someone on the outside needs to be inside.

And I heard that the people in Birmingham Alabama, there's a big opera loving club down there that hosted parties for the Met when they came to town.

And I heard that before the company left for the tour, being I'd received a letter from the people in Birmingham saying, we really looking forward to coming.

You're coming. So we got parties and what have you.

But we really don't want the black members of the company to attend.

There were three black members of the chorus and myself and Laintine.

Now, Laintine did not take the train.

I took the train, Laintine flew down.

And I heard recently that the Baltimore Hotel initially did not want to accept her, where a lot of, you know, a lot of the people stayed but being insisted.

But, I along with the three members of the company were booked in the Peachtree Manor Hotel, which is up on the top of the hill in the back of the Baltimore, nice hotel.

And one Sunday morning, I took the bus and that's one of the, cause my first trip to Atlanta, I took the bus and I passed a big church on Peachtree Street.

And there was a long line of blacks dressed in their Sunday best, standing outside.

And on the steps of the church were two rows of men, white men dressed in their Sunday best determined to keep the black folks from coming into worship.

So I stayed on the bus when downtown got off.

And this was about the time when things were beginning to be the black community was beginning to push for change, 1962.

And I passed a white tower and there was a line of young blacks dressed, very nicely.

Standing outside, door was barred for their getting in to have a hamburger.

And I passed a barber shop and it was a big barber shop.

And I noted that in the front chair, a couple rows of chairs, there was a black barber.

I could tell he was light skinned, but black barber.

I thought, gee, I think I'll get a haircut while I'm down here.

So I kept walking around, went back to the hotel and I thought, I would ask one of the black members of the staff there about the barbershop.

And Phil said, oh yeah.

He said, that's the Herndon Barbershop.

Herndon was a black family.

Well, to do, I think that Mattiwilda Dobbs, was related to the Herdon.

And he said, you know, you can't get your haircut there.

I said, what do you mean?

He said they don't cut black folks here.

So I determined, okay.

The next day I went down to the barbershop.

I was reading a book on Caruso's life.

And I walked in and there were two rows.

I mean, it was a big barber shop and there was a seat facing the entrance door, barber chair, but no one could get, because it was up against the wall, just there for maybe a decoration, but there was a big white fella sitting in it, in overalls.

So I walked in and I sat down in one of the chairs and the barber in the front was cutting someone's hair.

And I sat there for about five minutes.

So, and he came over to me.

He said, can I help you?

I said, yeah, I'd like a haircut.

He said, well, are you from around here?

I said, no.

He said, are you Indian?

I said, no, I'm America.

So he walked over to the guy, seated in the chair in front and said something to him.

I didn't hear what he said, but I think he said, well, he said, he's Indian.

I couldn't swear to that.

'Cause I heard the guy in the chair grunt.

So the barber turned around, came back.

He said, well, there was a barber, two chairs back.

There are only two barbers working one in the front and then one in the back of darker skin, he was cutting someone's hair.

He said, well, the fellow, when he finishes there, he'll cut your hair.

He said, fine, thank you.

The customer finished and he left, I went back and the barber was so excited.

He was shaking.

Like his hands were like this.

He was so excited because he knew who I was.

And it wasn't that great a haircut because he was so nervous.

You know, his hands were like that, that was one experience that will live with me because on that day, the Herndon Barbershop cut a black man's hair.

Maybe it was the first time in their history.

So there were those things, there was no way that a black person could get, or have a trip anywhere in the country, not just the south, but the north as well without running into stuff.

When I was in the army chorus and I'll show up here, but it was on the army chorus, Captain Sam Leboda did not take me to Dallas on one of the trips because he knew I wouldn't be able to stay in the same hotel as my army buddies. Too dangerous or, yeah, wow.

- So yes, that is the American story that a whole lot of people today don't wanna hear, you know, this whole argument against critical race theory.

What is that about? It's about telling people the truth.

Well, I don't want my children to grow up feeling guilty.

Well, often your children grow up feeling guilty after they hear the truth.

And you haven't done your job as a parent because it's your job to tell 'em that they're not guilty.

And you're telling the truth because you don't want them to fall into the same hole.

- Well, thank you for sharing.

Thank you for sharing that amazing story.

I wanna make sure before I forget that we're gonna save some time at the very end soon for questions and answers.

So there's a Q and A button at the bottom of this Zoom screen, not the chat button, but the Q and A, and please, and everyone who's watching.

Please contribute. If you have any questions for this incredible panel.

Let me introduce the next and maybe most special treat in store for everyone attending this event.

We're gonna take you inside the recording studio, where Ms. Denyce Graves was kind enough to record something for us in tribute to Marian Anderson.

It's my great honor to share this very intimate and moving performance with you tonight. Enjoy.

- Today, we are celebrating the extraordinary life of the great lady from Philadelphia, Miss Maryanne Anderson.

Brian Zeeger and I are delighted to perform one of her great spirituals that she's sang all over the world.

It's called 'Poor Me' arranged by Nathaniel Debt.

(piano plays) ♪ Sometimes I'm up ♪ ♪ Sometimes I'm down ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Yet still my soul feels ♪ ♪ heavenly bowned ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Oh breatheren ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ (piano plays) ♪ Although you see me ♪ ♪ Going along so ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ I've had my trails ♪ ♪ Here behold ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Oh breatheren ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Poor me ♪ ♪ Trouble will bury me down ♪ - So what you need to know is that song was given to me by Dr. Shirley and for so many years, for years, when I would run into Dr. Shirley, he'd say, you know, there's a song that Marian Anderson sang that you should sing, for years.

And then he sent it to me.

And it's just amazing that we're here this evening and that I sang that song, but I have it because of him.

- Wow.

- And I have to say, first of all, thank you, Denyce.

Just absolutely wonderful.

And I will also say that years later, when I interview Dr. Shirley for this documentary, that song had so touched me that I would start off the interviews by playing it and then taping the reactions of the person who was being interviewed their face as I played it.

And when I played it for Dr. Shirley, he said that it was his favorite Marian Anderson song, and it was mine.

And I think the reason that that comes full circle is the idea that the spiritual is, it encompasses the African American experience.

And I hope I'm not jumping ahead here, Michael, but to say that, that spiritual and the spirituals and Dr. Shirley taught me this too.

If you take yourself back in the time period of Marian Anderson, that is a spiritual classically arranged, maybe it was sang in the black church, maybe not exactly like that, but because it was classically arranged, it then went to audiences that would not hear spirituals on any kind of normal basis.

And even though she came after the fist Jubilee singers, and after Roland Hayes, the places that she went to in the world, that song connected her to the audience.

And it also connected the black experience that was happening in America to a European audience who would not have felt it or known it the same way.

And it opened doors for her.

- Wow.

- May I say this?

The spiritual, when people look at it and peel off the skin of those who sing it, they realize they've always, they themselves have had reason to sing and to speak.

And to say these, to give voice to these sentiments, because in the final analysis, there's not a different, we're not different races.

We are human.

There's one race and it's human, different ethnicities, but one race, if we were a different race, you're head would be protruding from a different part of your body than mine, protrudes from mine.

We are all human beings feeling the same pain, the same joy, the same elation, the same sadness may be triggered by slightly different things, but we are human.

And that peace, that spiritual says it all in such a powerful way.

That, I mean, it's hard for me to even speak after hearing it.

- Well, I wanna thank everyone on the panel for your thoughts and comments.

And I wanna open up the question and answer, and I wanna start with a question from Damon for Rita, which is for years, many of us were under the impression Ms. Anderson married a white man.

However, in later years I heard her husband was a light-skinned black man, which story is true?

Would you speak to that Rita?

- Yes.

Orpheus King Fisher as he was known was an African American man.

He lived in Philadelphia, moved to New York at some point, but he was when I wanna say African American, I don't wanna misquote the island that one of his parents were from, he lost his mother early in life.

He was a black man and many people think that, but he could pass. And when I say pass, I don't mean that he tried to pass.

Passing, it's a construct that we don't understand in this society.

So if you are that light and you're standing somewhere and someone mistakes you for a white person, you didn't pass on purpose. You were there.

And therefore, this is how you were seen.

So sometimes that was used to his advantage.

Sometimes he may have used it, but he was a black man.

- Thank you.

Another question. What year was Ms. Anderson born?

- 1897.

Now it is true that she sometimes augmented her birthdate by about five years, but she had the blessing of looking so young that she could do that and to enter something, she might have chosen to do that, but she was born in, 1897 one year after separate but equal Plessy versus Ferguson.

- And I'd just like to add to that and say that my voice teacher told me early on when I was an undergraduate, she said, Denyce, start lying now, you know, just start it now.

That was before Google and all that stuff.

- Another question that I'll put to everyone, but Rita, you can start visa v, Marian Anderson is, did she suffer from stage fright?

And I'm curious about George and Denyce in terms of your own career.

Is there any moment and Denyce, you spoke to that important 9/11 concert, but Rita, do you think Marian Anderson was ever anxious about performing?

- I'm gonna say this and I have no real right to, I think that most singers are concerned about the audience that they're going to go forward to sell a song.

That's why so many singers or great actresses and actors is because you must sell that song, but you must sell it to that audience.

And when that curtain opens, you don't necessarily know who's there.

And I think there's some emotion about that.

And in her 1939 concert, you can see this in the film.

And she says this, she didn't expect that many people to be there.

And for a moment she was overcome.

And then she closed her eyes and she sang.

And I'm sure in Finland where they'd not seen many black people, some of them never haven't seen black people, but she kept going.

So if she had any stage fright, she certainly got over it very quickly once she was called to the task.

But I think it's more of a concern about that audience and doing what you want to do and what you want to give, reading them and working with them to get that we going.

When you begin to sing.

- Any thoughts on stagefright from George or Denyce?

- Well, I would not want to approach a performance without feeling the energy that gets me going.

And without that, there's the concern.

Yes, I wanna do the best I can possibly do.

There've been some times when I've been, oh boy, but then I've got to come to a point where I commit myself to delivering the message of the text in the song and living the character that I'm portraying, if it's a recital, that character changes.

So I've gotta find that character in my own expression.

So I've got to go there and not worry about trying to please who's out there, knowing that if I go there, then I'm going to touch people in the manner that I want to touch them.

So I wouldn't wanna go out on stage without feeling that excitement, that, because if I didn't feel that then the performance would be as flat as a pancake.

- Denyce, anything to add, or should I move on to next question?

I spoke earlier about the performance that I sang at the Washington National Cathedral.

And during that time during President W. Bush's administration, I was appointed cultural ambassador to the United States and they sent me and lots of other magnificent artists all over the world to sort of dispel any stereotypes about Americans in general.

And there was a once a concert with Yo-Yo Ma and sometimes before concerts, the presenter likes to go out and make announcements and he was in the wings and he kept saying, can I go on, you know, can I go on, can I go on and they'd say, wait, you know, Mr. And Mrs so and so need to be acknowledged.

And he said, I'm always so nervous until I get out there.

And I would echo that I'm not a person who would think that I would've found myself on the operatic stage.

I was a incredibly shy kid, very, very awkward.

And so I would say, I'm not paralyzed before going on stage, but I'm incredibly nervous and I'm very, very nervous and excited until I start singing.

And then I relax.

- Can I add that? You just made me think of something.

The last time I sang with Birgit Nilsson was a Salome concert performance with the Chicago Symphony and Georg Solti.

And I'd sung Un'aura many times with her at the Met and this amazing woman who had a voice that just blew the walls out and drown out the orchestra.

So I went back to her dressing room before the performance and she was standing there all by herself like this.

And as I approached her, I was gonna kiss her on the cheek.

As I approached, she said, oh, I am so nervous.

Thought, you are nervous.

You have peeled the paint at the Metropolitan Opera in this row. You're nervous.

And she went out and she blew the walls out of the hall. I mean with no big deal.

So that is there.

It's there because you want to inhabit that role of whatever it is you're doing to the fullest.

And you don't want, you may have had a rough day, you know, you might have gotten a ticket on the way to the... You can't let that stuff get in the way of focusing your nervous energy so that it becomes performance, energy, so.

- Uncle Carelli was the same.

- Oh, yeah.

I covered Carelli and I remember for Romeo and Juliet, he was so nervous.

First performance, he cracked an interpolated high C at the end of the fight scene.

And I was in the house, was had to cover him.

And I was learning some music 'cause I was going ready to take off to go on a concert tour after the recital tour.

And at 10:30, the door to the dressing room where I was working opened and Rudolph being stuck his head and said, well, you're on.

- Oh my God.

- What?

He said, yes, he just canceled.

- Oh my God.

- So I had to put on the costume and go out and finish the opera.

Now you can Franco Corelli over six feet, tall, handsome, and here comes George Shirley, you know, I mean five foot nine, but - handsome It worked and I had to go out and do it.

But he was a very nervous man in part, I think, because the Met kept insisting that he sing in French and most Italian singers don't sing in anything but Italian.

So it sort of didn't work to keep him in line.

And we did.

And we did a benefit performance at the one night and he sang a new Paltan song, sang it beautifully.

And I was in the wings getting ready to go out.

And I said, bravo Franco.

He said, (speaking in foreign language). And you know, what a tragedy in such a fantastic voice and presence, but the nerves got the better of him.

So the nerves are there without them.

There's no performance, but if they get to the point where they rule the day, then that's the problem.

- Well, in a nice full circle to the 1939 concert, here's a question really for Rita.

Did Ms. Anderson sing at the 1963 March on Washington at the Lincoln Memorial where Dr. King delivered his 'I have a dream speech'. If so, do you know what she sang?. - She sang, 'He's got the whole world in his hands'. And I think that it was near the end of her singing career 'cause to 1963.

And she made her way through the crowd.

It was a crowd that wasn't expected.

So she was late and she was not there to open the concert as she was supposed to.

Mahalia Jackson did that and did quite an awesome job of it. But by the time she got there, she still was able to sing.

'He's got the whole world in his hands'. - Wow.

Well, unfortunately this tempest is fugiting.

We are out of time tonight, but this was a great pleasure.

And I wanna thank Rita Coburn, Denyce Graves and George Shirley for joining us tonight.

Also a deep bow of gratitude for Robert F. Smith, Mercedes Bass, Carnegie Hall, and The Better Angel Society for making this event a reality.

On behalf of American Masters channel 13 and the WNET Group.

I'd like to thank our funders again and thank you to all of our guests for the evening for joining . Tomorrow night, February 8th, at 9:00 pm on PBS.

Please watch Marian Anderson Program on American Masters.

Thank you. And good night.