On January 1st, 1984, New York’s public television station would make TV history with its transnational live broadcast, “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell.”

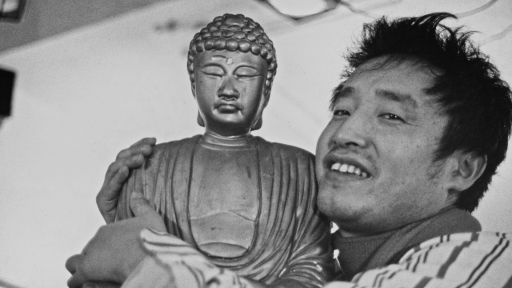

Challenging the technical possibilities of television at the time, the event linked live satellite broadcasts between New York, Paris, South Korea and Germany to celebrate the dawn of the new year with host George Plimpton and a suite of performers, including Laurie Anderson, Salvador Dalí, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Peter Gabriel, Philip Glass and many more.

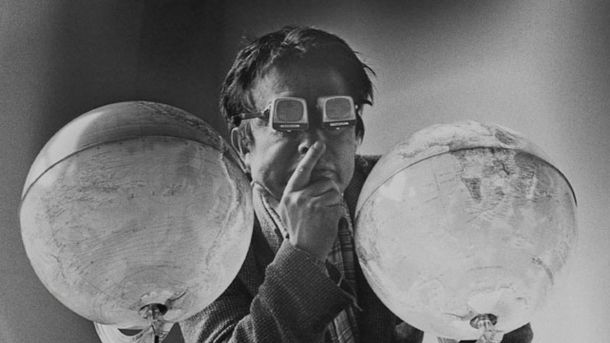

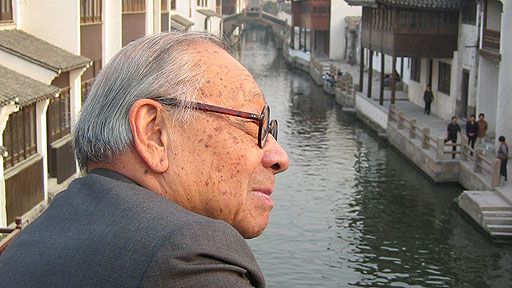

The brain child of video artist Nam June Paik, “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” was a response to the evolving media landscape. “George Orwell was the first media prophet and philosopher, however, he emphasized only the negative aspects of the media: TV as Big Brother. . . This show is symbolic of how television can cross international borders and provide a liberating information/communications service,” said Paik.

Produced by WNET/Thirteen’s experimental Television Laboratory, in which Paik was artist-in-residence, the live studio footage shot in New York was directed by WNET’s staff director, Bob Morris. Morris spoke to American Masters about his time working with Paik and his memories from that monumental day in 1984.

How did “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” come to WNET and how did you get involved?

I’m not sure how “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell” came to Thirteen. I had worked on many projects with Nam June Paik in the TV Lab so we were well acquainted with each other. I don’t know if he requested me or if it was because I was a staff director. That being said, I was honored to work on this project.

We are all used to live broadcasts and live streams nowadays, but in 1984 this must have felt revolutionary. How were you and people around the office talking about this exciting moment of intercontinental live broadcasting?

Short of the Olympics, there were very few projects in which you could reach a global audience. Technology what it was in those days was not the same as it is today. Today, you could do a FaceTime video with anyone, any place in the world, but in 1984 the technology was very different. So in one sense we felt like we were doing a regular television program, but in another sense we were doing something that was really innovative.

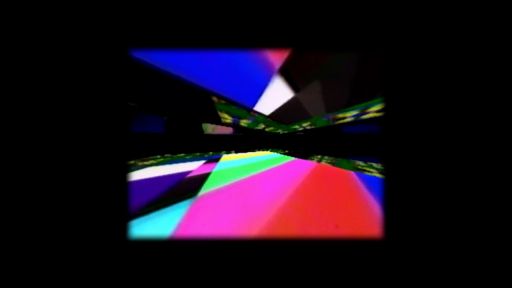

There are not many times when you get to do an intercontinental – interactive program. I was one of two directors who worked on this program. I directed the studio portion and Emile Ardolino directed the effects that went into the program. So if my memory serves me, I would direct the studio, send the feed to Emile and he would send it back with certain effects that Nam June would instruct him to do and I would put them on the air.

Did anything stressful or funny happen live?

I think that it was more stressful knowing that we were reaching an audience of 24 million people, but in the big picture, whenever you’re directing it’s no different than if your audience is two people or 24 million, you’re always trying to do your best. For me, the easiest thing to do is to direct cameras in your studio in which you have total control. In one instance, we were supposed to do a scene where Merce Cunningham was dancing with himself. This was to be achieved by sending our signal of Merce dancing to Paris, and they would send it back. The signal from Paris because of satellite time was 2 seconds delayed and would become the background for Merce. However, when Merce started dancing, Paris did not send the delayed image back to us. I quickly tried to do a digital delay to compensate for this lack of a background. Thankfully after a few seconds, Paris came through. It was a tense moment.

So many great artists participated, including Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Philip Glass and Oingo Boingo. What was your favorite performance from the show?

I have a lot of favorite memories of that day. I loved the Thompson Twins, Merce Cunningham and John Cage (who was already a major artist).

How do you view Nam June Paik’s relationship to public media?

I don’t think anyone really realized what a major force Nam June was at that time. Nam June was an artist whose work was very counter to broadcast television standards. He loved spontaneity, he loved entropy – those were concepts that were not ordinary in broadcasting. I am not sure whether the larger viewing audience was ready to accept his view of art.

https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/archive/interview/philip-glass/

Broadly speaking, how do you view public media’s role in the arts?

These days, broadcasters of every type are searching for audiences. Public media’s role is to introduce new art forms to the public. No one else in the broadcasting landscape is doing this and we can hardly afford to do this. If you want the same-old-same-old programs, go some place else. But I think as a public television station, we are obligated to give the viewing public something they have never seen before. So, perhaps, as a viewer, you didn’t like “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell,” but afterwards you can say you know who John Cage was, you know who Allen Ginsberg was, or you discovered Merce Cunningham. If that’s all we accomplished, it was a good day.