“I just want sashimi. Kitcho. 45th Street. Look up in the phonebook. Say who it’s for. Yoko Ono, not me. Say it’s for Yoko Ono. Otherwise I don’t get it.”

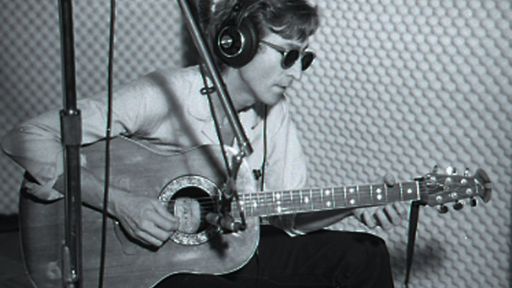

It was August 1980 and John Lennon was back in the studio. Five years earlier, Lennon had famously walked away from the music business, from the fame machine, from everything. He baked bread, took care of his son, Sean and spent his time, as he put it, “watching the wheels go ‘round and ‘round.” But now Lennon was back in the recording studio and for the first time in his life he was perhaps truly, unreservedly happy.

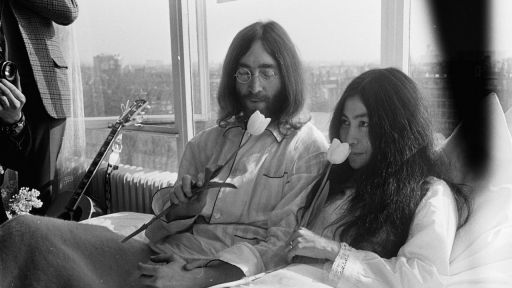

It had been a long, difficult journey to get there. The Nixon administration had used the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to tap Lennon’s phone and put him and Yoko under 24-hour surveillance in an attempt to deport him. The pressure had taken its toll: for years, Lennon had been consumed by drink, making, on more than one instance, a public ass of himself. He had even been kicked out of the Dakota for eighteen months by Yoko — the great love his life.

But now, Lennon was at The Hit Factory recording what would become “Double Fantasy.” The songs Lennon brought into the studio didn’t speak to the pain of his past — he was done with all that. These songs were about the life he had built with Yoko and Sean: “Watching the Wheels”; “Woman”; “Beautiful Boy.” Each song spoke to the deep contentment Lennon had found after years of personal struggle and doubt.

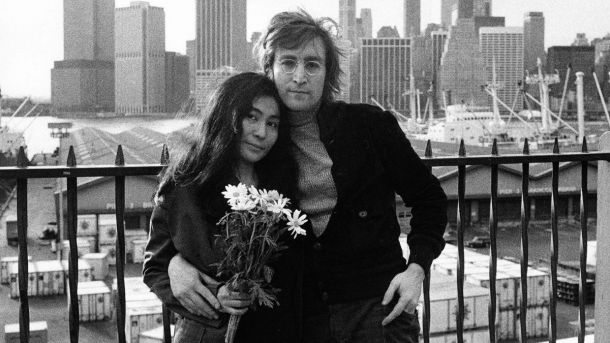

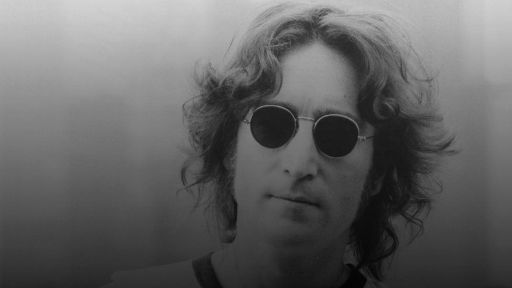

My American Masters film, LENNONYC, is about that extraordinary and — for Lennon — entirely unexpected journey. It is the story of how one of the most famous and influential artists of the twentieth century found redemption, not in the public adoration he so desperately craved in his youth, but in the quiet, simple pleasures of fatherhood. But it is also, in many ways, an American immigrant tale. John Lennon came to New York City in 1971 seeking something many immigrants have sought before and since: freedom. The freedom to be himself and not “Beatle John,” the freedom to love his wife and muse without being publicly scorned for it, and perhaps most of all, the freedom to live a normal life. That, more than anything else, is what John Lennon loved about New York City: the ability to go out for a coffee, or to shop for a jacket or to take a walk in Central Park without drawing attention. Only in New York could Lennon could be truly free.

I made LENNONYC a decade ago to celebrate what would have been John’s 70th birthday. At the time, I wanted to make a film that would capture the real man, not the myth that had grown in the years since his tragic death. I wanted viewers to feel as though they were in the room with John, spending time with him as he recorded with the Plastic Ono Elephant’s Memory Band, or with Phil Spector, or finally — triumphantly –with Yoko Ono on “Double Fantasy.” To some extent, I hope I achieved that goal. That LENNONYC conveys a sense of emotional intimacy, that viewers feel like they are with John as he plays around in the studio with his fellow musicians or draws at home his son Sean. I think it is this quality that makes LENNONYC as uplifting to watch a decade later on what would have been John’s 80th birthday.

Forty years on, John Lennon’s murder still makes no sense. There is no larger meaning to be taken from his untimely death. No silver lining. He was shot by a deranged fan who never should have had access to a gun and who wanted to make a name for himself. John Lennon was taken from all of us — but especially Yoko and his sons, Sean and Julian — way too soon. We miss John terribly to this day.