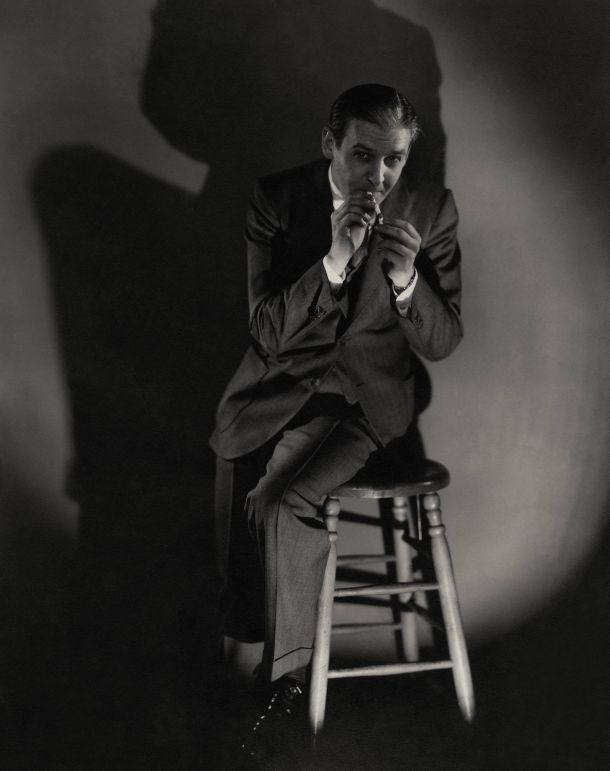

Studio portrait of American newspaper and radio commentator Walter Winchell half-sitting on a stool and lighting a cigarette. (Photo by Edward Steichen/Condé Nast via Getty Images)

By Ben Loeterman

Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, written, produced and directed by Ben Loeterman and narrated by Whoopi Goldberg, traces the fascinating arc of a flawed protagonist. The film explores the phenomenon Walter Winchell pioneered: gossip, celebrity, politics and news — all rolled into one. It was nothing less, concluded the New Yorker in its 1940 profile, than a “new form of journalism.” At his zenith, his combined newspaper and radio audience rose to 50 million — two thirds of American adults. Decades later, an alliance with Joseph McCarthy and feuds with Josephine Baker and Ed Sullivan turned his audience against him and forced him into obscurity. His rise and fall embody today’s fast-paced, celebrity-driven, politically charged media circus.

“Winchell’s primary objective is to explain the 20th century to his millions of readers,” a friend eulogized at his death. “The fact is, however, that historians will be unable to explain the 20th century without understanding Winchell.” Winchell’s is the origin story of fake news; there could not be a timelier moment to unpack it for a wide audience. Our film breathes new life into Winchell’s columns and scripts, drawing on rare recordings and, especially, a newly digitized collection of his work at the Billy Rose Theatre Collection of the New York Public Library. Winchell’s own words comprise nearly a quarter of our script, voiced on-camera by actor Stanley Tucci.

Walter Winchell grew up poor in East Harlem, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. He quickly rose from vaudeville hoofer to Broadway blabber by posting gossip about his acting troupe on backstage bulletin boards. His career took off with a notorious tabloid, the New York Evening Graphic. That became a springboard to Hearst’s Daily Mirror, to national syndication, and to the new medium of radio. Winchell’s signature columns were crammed with snappy, acerbic banter. His broadcasts were slangy, delivered in machine-gun staccato while clacking a telegraph key alongside. Each week, a growing audience tuned in to hear him sign on, “Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. America, from border to border and coast to coast and all the ships at sea. Let’s go to press!”

Winchell invented a new form of newspaper writing and radio delivery. He created slang where falling in love became “pashing it,” or “Garbo-ing it,” while newlyweds awaited a “blessed event” or “the stork,” unless their relationship was “phffft” or about to be “Reno-vated.” Winchell would string together partial phrases, thinly veiled rumors and mere allegations. He had a knack for spinning tales about famous people, exploiting his contacts and trading gossip with friends, often in return for his silence.

A plug in Winchell’s column could guarantee any show a successful run or raise the profile of a starlet. Equally, a dig in the column could tarnish or even destroy professional reputations, as acclaimed performer Josephine Baker and talk-show host Barry Gray learned the hard way. Winchell spewed searing attacks in print and on the air at Baker after she publicly complained that she was the object of a racial snub at his favorite haunt, the Stork Club. Her career never recovered. After radio talk show host Barry Gray invited Baker to explain what happened on his radio show, Winchell viciously and repeatedly attacked Gray as well. His shrill outbursts became a cause célèbre, stirring one rival, Ed Sullivan, to declare, “I despise Walter Winchell because he symbolizes to me evil and treacherous things in the American setup.”

Yet Winchell was nothing if not contradictory. When he wasn’t exercising his power to destroy careers, he was using it to elevate “Mr. and Mrs. America,” publicizing bureaucratic injustices and letting the common man and woman in on the secrets of the rich and powerful. The populist tinge to his early work grew into a full-blown political consciousness following a 1933 meeting with newly elected Franklin Roosevelt, in which the president recruited Winchell to promote his agenda to America. Winchell became an effective tool in Roosevelt’s effort to persuade an isolationist-leaning America to intervene in in Europe’s looming conflict. He was also the first major commentator to directly attack Adolf Hitler and American pro-fascist organizations such as the German American Bund.

After President Roosevelt’s death, Winchell lost his moral bearings for nearly a decade. Personally, he faced successive tragedies: broken marriages and failed relationships, the death of his young daughter and his grown son’s suicide. Professionally, he played all sides, schmoozing with Al Capone even as he befriended J. Edgar Hoover. Having served as Roosevelt’s most reliable mouthpiece, he then inexplicably championed McCarthyism, having been recruited to the cause by the senator’s young aide, Roy Cohn.

Winchell met failure only when he attempted the jump to television. He was simply not telegenic. “The familiar hat and pulled down tie are a throwback to the old newspapering days,” one critic smirked. The energy he projected so forcefully on radio looked manic on TV, bordering on crazy.

It is a cruel irony that Winchell created the cycle of celebrity – the meteoric rise followed by the crushing fall – and then fell victim to it himself. “I died on October 16, 1963,” he said the day his flagship paper, the New York Daily Mirror, folded. His final breath, drawn nine years later, was just a formality. “He was not only present at the creation of modern journalism,” concludes biographer Neal Gabler, “in many respects he was the creation.”