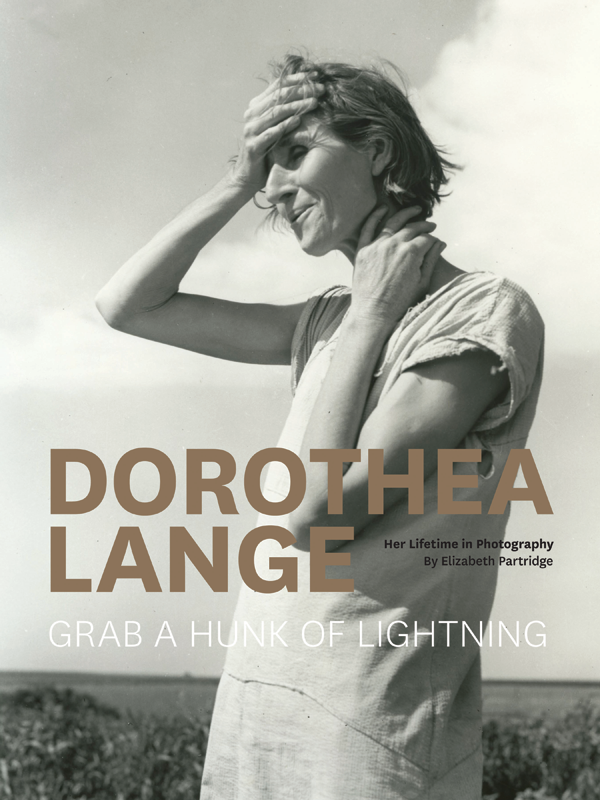

The following book excerpts are from Dorothea Lange – Grab a Hunk of Lightning: Her Lifetime in Photography (illustrated; 192 pages) by Elizabeth Partridge. Text used by permission and published by Chronicle Books. Text copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Partridge, all rights reserved.

—–

APPRENTICESHIP

Despite her many truancies Dorothea managed to graduate from high school. Joan asked what she planned to do next. How was she going to support herself? Dorothea knew: she had no camera, and had never taken a photograph, but she was sure she wanted to be a photographer.

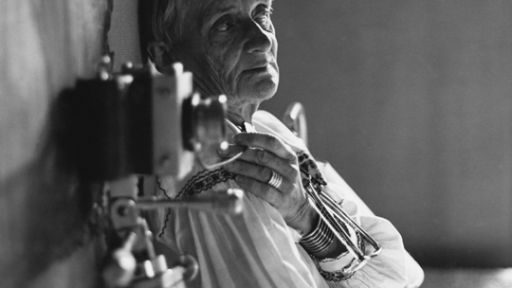

Dorothea set out on her own course of apprenticeship, inquiring first at the portrait studio of Arnold Genthe. He’d recently moved from San Francisco, where he was known for his photographs of Chinatown and the 1906 earthquake. Genthe gave her a job answering phones and setting up appointments. Soon he taught her to change the large glass plates in the cumbersome studio camera, to retouch the nega-tives, and to mount the prints.

Genthe and his studio opened up a whole new world for Dorothea. It was a world of privilege, wealth, and opulence. It seemed miraculous and luxurious to Dorothea. As carefully as she watched how Genthe ran his studio, she was studying him as well. He struck her as highly creative, a man who passionately loved life, women, even the new color photography. “He was an artist,” she said, “a real one, in a narrow way, but it was a deep trench.” Taken with his assistant, Genthe gave her one of his old studio cameras.

Over the next few years Dorothea worked with several other portrait photographers, and learned to operate the big 8 × 10 studio cameras. Meeting an itinerant photographer and learning he had no darkroom, she helped him convert an abandoned chicken coop in her backyard where she still lived with her family. He would come by with his exposed glass plates to develop and print in the tiny darkroom. Dorothea watched carefully and soon was working alongside him, absorbing his darkroom techniques.

Dorothea even put up with the classroom again and enrolled in a seminar taught by Clarence White, a master of pictorialism, at Columbia University. She was mystified by his teaching style, his awkward, bumbling ways, but was taken with the way he lived an instinctive, nonformulaic photographic life. He believed his students should take photos of the everyday life around them. Dorothea attended class, but usually refused to do the assignments. White didn’t seem to mind. Once again, Dorothea stood on the sidelines, observing, taking in, learning. “I was immensely curious, and interested, even eager, to find out as much as I could about everything that I could. But I always felt and acted as though I was an outsider, a little removed. I never was in the middle of any group.”

By the time she was twenty-two, Dorothea knew how to put together a darkroom, run a business, and please wealthy clients. She was restless, ready for a new challenge. “I wanted to go away as far as I could go,” she said. In January 1918 she and her friend Florence Ahlmstrom headed west, intending to go around the world. They made it as far as San Francisco where suddenly their plans abruptly changed when all their money was stolen by a pickpocket. The next day, Dorothea found a job at Marsh and Company on Market Street, working at the photofinishing counter, and Florence was soon employed at Western Union.

Somewhere between leaving New York and taking her new job at the photofinishing counter, Dorothea shed her father’s name, Nutzhorn, and took Lange, her mother’s maiden name. She was intent on reinventing herself, closing off the painful parts of her past. It wasn’t until after her death that her husband and children learned she’d changed her name. Even for those closest to her, everything about her father was tersely summed up in one tight phrase, and no more: “My father abandoned us.”

—–

TO THE STREETS

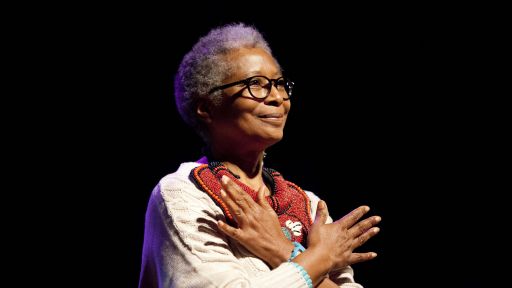

As much as she enjoyed working with her wealthy clients, Dorothea was keenly aware of the distress on the streets outside her studio. Millions of people were out of work now with no end in sight, and painfully little government relief available. “I was aware there was a very large world out there that I had not entered too well, and I decided I’d better,” she said. She wanted to be involved and be useful, though she wasn’t quite sure how.

Looking down from her second floor studio window on Montgomery Street one day, she saw an unemployed, down-on-his-luck man pause at the corner below, uncertain which direction to take: one way led the waterfront and wholesale districts, another to the seedy flophouses and prostitution of San Francisco’s notorious Barbary Coast. Dorothea was afraid, but determined. She loaded film into her cumbersome studio camera and headed for the streets below, “driven by the fact that I was under personal turmoil to do something,” she explained.

I will set myself a big problem. I will go there, I will photograph this thing, I will come back, and develop it. I will print it, and I will mount it and I will put it on the wall, all in twenty-four hours. I will do this, to see if I can just grab a hunk of lightning.

Near Dorothea’s studio, a woman nicknamed the “White Angel” ran a soup kitchen for the unemployed men who drifted into town looking for work, surviving on handouts.

Despite being nervous about photographing in the slums of San Francisco, Dorothea headed straight there. She didn’t linger long in the crowd of hungry, bewildered men, stopping only long enough to take three exposures. “I wasn’t accustomed to jostling about in groups of tormented, depressed and angry men, with a camera,” she said. “I was afraid of what was behind me—not in front of me.”35 She worried someone would grab her camera from behind, or sneak up and hit her.

Dorothea developed her negatives, made a print of her best shot—a lonely-looking man facing her, the crowd behind him turned away—and pinned it up on the wall of her studio: “I photographed those demonstrations and the next day they were on the wall, done and mounted.” Her wealthy portrait clients were taken aback by the image, and asked what she planned to do with it. She had no idea. She only knew she felt compelled to go out again, to be on the streets with her camera, photographing. With increasing frequency, Dorothea would head out of her studio with her camera and roam San Francisco’s poorer districts. To her relief, she found no one objected when she quietly set up her camera, took a few shots, then slipped away. Her “cloak of invisibility,” cultivated years earlier on the Bowery, protected her camera as well.

In the spring of 1934, San Francisco braced for a big demonstration on May Day. With no end in sight to the depression, people’s desperation rose and strikes and demonstrations of the unemployed increasingly turned violent. Dorothea was determined to go out with her camera despite the violence. “I had more confidence then, because I had gone down with the dregs,” she explained.

A few months later, several of Dorothea’s May Day photographs were exhibited at a small gallery where they were seen by Paul Taylor, an associate professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley. Since the late 1920s he’d been studying Mexican labor in California’s fields. He took extensive notes in the field, as well as photographs he snapped with a pocket-size Kodak camera. But Paul immediately saw the difference between his photographs and hers. When he saw the show, he had just finished writing a revealing, thoughtful article on the San Francisco General Strike, the latest and bloodiest in the long series of disagreements between workers and employers that had boiled over in July. The governor had declared a state of emergency and the National Guard was set up at the waterfront with steel helmets and bayonets, even machine gun nests.

Paul asked Dorothea if he could use her May Day photograph of a man at a microphone to accompany his soon-to-be published article. Dorothea was pleased her photograph had found a use. The image became the frontispiece of Paul’s September, 1934, article in Survey Graphic magazine. The editor paid Dorothea fifteen dollars, her first payment for work outside her studio.

—–

WORLD TRAVELER

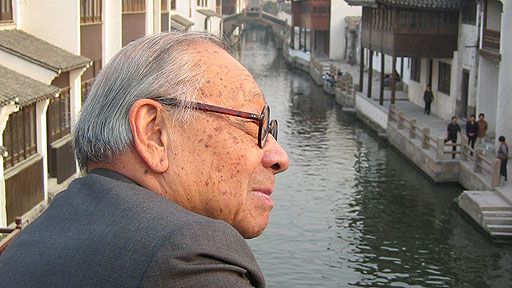

Early in 1958, Paul [Lange’s husband, Paul S. Taylor] was asked to consult in Asia by the Agency for International Development (AID). For several years he’d been a consulting economist with government agencies and private foundations on community development and land use in developing countries. While others focused on increasing output through mechanization, irrigation, and efficient crop production, Paul wanted to help policy makers understand the importance of local family farms. While his were not the prevailing views, Paul tackled his job with perseverance, and optimism that small farms could survive, and even flourish.

Knowing he would be gone for months, Paul wanted Dorothea to accompany him. She was reluctant, unsure her health could take the long trip. She asked her doctor what he thought. “What’s the difference whether you die here or there,” he replied. “Let’s go!”

In July Dorothea and Paul took off on an eight-month odyssey, flying to Japan, traveling on to Korea, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. They continued west through Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Bali, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, finally heading home through Europe.

Dorothea was immediately overwhelmed by what she experienced. “Can Asia be photographed on black and white film?” she wrote in her journal. “I am confronted with doubts as to what I can grasp and record on this journey. The pageant is vast, and I clutch at tiny details, inadequate.”

From the very beginning, Dorothea struggled with her health, challenged by rough travel and unsanitary conditions. “Photography is at a standstill,” she wrote in her journal in Korea. “Health precarious. My mind is not easy because I want to work, and my inability to cope with the difficulties is galling to me. I do not do it. And my excuses are good. Nevertheless, I do not do it. I see plainly that I am old, and the burden of age is not being accepted. Who can photograph Korea?”

Dorothea persisted. “The market photographing and the street photography is very difficult indeed. I am immediately the center of a pushing mob of children and curious adults if I stop walking for a minute. If I continue to move on they become a parade. I tried it all again today with Paul’s help. Nevertheless, Korea has gotten into the bloodstream. I wonder if any of the other countries we will visit will have such a hold.”

But Dorothea was also unencumbered by old, familiar limitations. With no assignment to fulfill, no deadline to meet, she could follow her instincts. She was drawn to themes she was so well-versed in: people working in fields, carrying babies, washing clothes, gathered in open markets. Dorothea distilled what she observed down to an essence: the lyrical grace of a woman walking with a burden on her head, shoes slipped off outside a doorway, a child’s serene face. Despite her physical fraility, she was working at the height of her visual powers, with a freedom she’d never experienced.

There were moments when time stood still and found her. Some she caught with her camera, others she missed, and lamented in her journal.

The older women on these crowded streets as they pass me, an older woman, sometimes from under the parasol, sometimes from under the head burden, look at me seriously and intently. Our eyes and attention meet, and in it I sense a Recognition which needs no words. We do not smile as we pass. We greet one another in a way to be remembered. I wish that I could photograph this.

She focused, without consciously meaning to, on the bare legs and feet she saw so often throughout Asia. In Bali, their twelve-year-old guide asked Paul if Dorothea had a special camera for photographing legs.

Sharing a hotel room with Paul, closer than ever to his daily routine, she admired his steadfast work habits as he went into the field, attended meetings, met with dignitaries, and filled out tediously detailed reports. Still, she was not sure of the AID work he was so deeply committed to. In Vietnam she wrote in her journal, “If American aid moved out of Asia, if they had the courage to stand up to us, would, in the long run, these countries be in a better position to take their place among nations? Are we interrupting the course of their development? The AID program and its mores cause uneasiness. We’re like a conquering nation.”

After India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, Dorothea and Paul flew to Moscow, and on to Germany in early January 1959. Desperately sick with a high fever, Dorothea spent ten days in bed. Outside it was bitterly cold, inside under a thick feather comforter, she was warm. For the first time in decades Dorothea heard the German dialect she’d grown up with, and feverish memories of her childhood flooded her. “The people, so nearly forgotten, have come forward in character and colors,” she said. She thought of her grandmother Sophie, hearing again the sound of her sewing machine, remembering the white ribbons and bonnet she wore. The forgotten relatives were so vivid, so present, Dorothea thought she could write a book—a slim one—about each of them. It would be “just a mass of tiny details, the brooches they wore, for instance, with seed pearls, the winter hat of Aunt Caroline, her clean hands with the square fingernails. Could I ever write of my father—so hard that would be?” Paul told her he’d found twelve entries in the phone book with her family’s last name. “Let sleeping dogs lie, say I,” replied Dorothea.

The fever burned out, and they could go home. Home to family, to a new grandchild, to Dorothea’s darkroom so she could see what she’d caught on film.

I sit in the kitchen. Three months we have been home. I am waiting for the potatoes to be done; I have a head full of this and that, how to manage, what to do, details of everything, work undone, tensions and splinters. A clear high sweet sound reaches me, and fills me. A little bell. There it is, under the dark and dreadful eaves where we hung it, hoping that the winds of the Pacific would make it sing of that glittering Sunday morning in the miraculous temple of Bangkok. The sound is faint, but clear. Hello and goodbye to Bangkok, I say, as the potatoes finally boil.

Paul was soon off again, this time to Cuba, without Dorothea. But when he was asked by the United Nations to look into the community development programs in Ecuador and Venezuela, Dorothea went with him. In mid-July they flew to Guayaquil, Ecuador. It wasn’t long before Dorothea wrote in her journal that it was an “ugly and terrible” city. Eager to get out, they headed into the Andes and over the mountains into the Amazon basin so Paul could see for himself the land reform projects there. They were warned the Indians in the Amazon Basin were “killers.” Dorothea protested. “But we Americans, with our money civilization, are in another sense savages, and we spread our ways and influence and poison.” On they went to Venezuela, where they hurried out of noisy, crowded Caracas to see the two and three acre allotments the Indians and mestizos farmed with help from a community development program.

After seven weeks they returned, Dorothea resolute this time in her desire to stay in Berkeley. “I thought I was going to live a quiet life. Here, at home,” she said. “All those grandchildren had shown up by then.” Paul’s desire to travel intervened once again. In early 1962 Dorothea had a prolonged stay in the hospital for two major surgeries. She recovered in time for Steichen to fly out to Berkeley during the summer to choose some of her FSA prints. He included them in his upcoming show, “The Bitter Years: Rural America as Seen by the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration.”

By the fall she felt healthy enough to join Paul in Egypt where he was teaching. On her way to Egypt she stopped in New York, arriving the day before the Bitter Years exhibition closed. She was shown through the gallery by John Szarkowski, the young assistant photography curator who would be taking over Steichen’s position. One of her photos opened the show: the upper torso of a thin, weather-beaten farmer against the sky, paired with Arthur Rothstein’s photo of a farmer and his son running through a dust storm toward shelter. As they walked through the exhibit, they approached a photo of Dorothea’s. Steichen had airbrushed out two men in the background to make the image more impactful. Knowing how temperamental Dorothea was about her work, Szarkowski was anxious, worried how she would react. When Dorothea saw the photo her mouth dropped open, and then she laughed at Steichen’s sheer gutsiness in daring to do such a thing. “And from the moment she laughed,” Szarkowski said, “I loved her.”

Dorothea flew on to Egypt, and spent the spring of 1963 in Alexandria with Paul. Noticed and surrounded by people the moment she appeared, Dorothea found it nearly impossible to photograph. They left the city as often as possible. A trip along the Upper Nile and a ten-day visit to Sudan gave Dorothea rich material to photograph. “I enjoy looking quietly and intently at living human beings going about their work and duties and occupations and activities as though they were spread before us for our pleasure and interest,” she said. “And also to be only dimly self-aware, a figure who is part of it all, although only watching and watching.”