Dyanna Taylor interview on the COLORES! series – a production of New Mexico PBS, KNME-TV

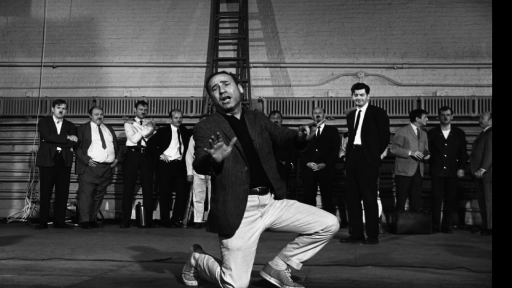

See Dyanna Taylor at work on the American Masters film Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, which she directed, produced, wrote and narrated. A Peabody- and five-time Emmy award-winning cinematographer, Taylor is the granddaughter of photographer Dorothea Lange and writer/social scientist Paul Schuster Taylor. Her other documentaries and works for PBS include American Masters — Ernest Hemingway: Rivers to the Sea, American Masters: F. Scott Fitzgerald – Winter Dreams, ART21, Great Performances —Porgy and Bess: An American Voice, Great Performances — Swingin’ With the Duke: Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis and episodes of American Experience and the Evolution series.

Director’s Statement

Dorothea Lange was my grandmother. She was brilliant, charismatic, complex and her still camera was her muse. Growing up surrounded by her still photographs, which were everywhere — in stacks, in drawers, tacked up in her workroom — left an indelible impression on me, both personally and artistically. Ever since I began my career in filmmaking, I’ve wanted to make a film which would express the true breadth of her work and the ways she perceived the world.

Over the years, as we spent time together, she taught me how to see — to understand that nothing is as it appears at first glance. When I was 10 years old in California, I collected a few rocks and shells in my hand and thrust them toward her, probably seeking her approval. Boasting, I said: “Look Grandma, look at these!” I did not get the response I’d hoped for.

She looked at me with her deep, commanding gaze and said sternly: “Yes, I see them, but do YOU see them?” And she snapped a photo of the shells in my outstretched palm.

I felt dismissed, but also challenged. From that moment on, my grandmother’s words in my mind, I perceived the world differently. To this day, along with everything I learned from her about composition and framing, I carry a sense of the truths found beneath the surface of things, as much an approach to art as a philosophy of life.

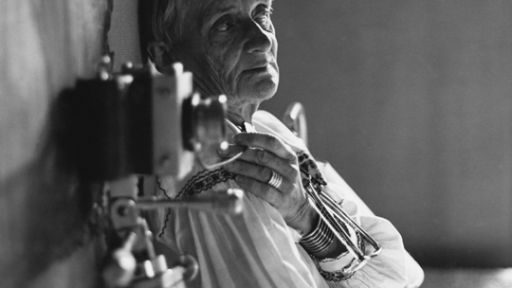

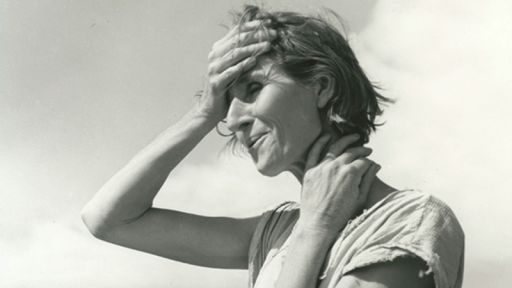

Most people know Dorothea from her penetrating Depression-era photos such as “Migrant Mother,” images that portrayed the anguish of the times and shaped the way America came to know itself. But beyond those familiar photos, Dorothea’s body of work, which spanned five decades, is equally powerful and compelling. She often said, “A photographer’s negatives become his biography.”

What few people know is that Dorothea’s ability to portray the challenges of the human condition came from her own pain and infirmity. As a child she contracted polio, which left her with a withered foot. Each day, this petite little girl would walk alone on the streets of the Bowery on New York’s Lower East Side to meet her mother, who encouraged her to “walk as well as you can.” Dorothea would hide her limp and make herself, in her words, “unseen” — safe from unwanted attention. Resourceful and courageous, she transformed the lessons learned from her disability into an artistic strength. Later in life, Dorothea would say she “wore an invisible cloak” when approaching her photographic subjects so her presence would not influence them or the resulting images.

Grab a Hunk of Lightning also explores the confluence of artists at work and in love. My grandmother had two major relationships: first her marriage to Maynard Dixon, the Southwest painter, and later her 30-year marriage to and collaboration with my grandfather, Paul Schuster Taylor. He was an unorthodox economist who insisted that field observation was more important than studying statistics at a desk. His specialties were migrant agricultural labor, the survival and importance of small family farms and, as corporate agriculture expanded, critical issues surrounding access to and fair use of water. From the first time Dorothea accompanied him (as his so-called “typist”) on a trip to study field labor conditions, their personal and professional lives entwined. Some of Dorothea’s greatest photographs came out of their rare creative partnership.

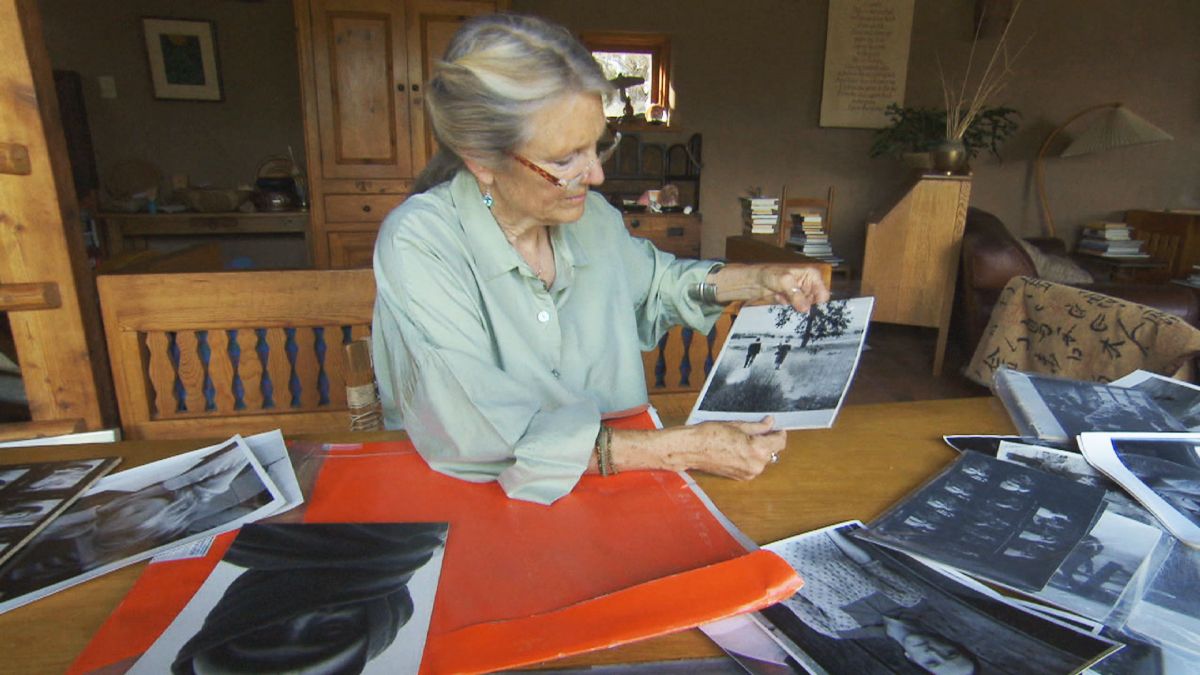

I have made a number of films about artists, their muses, struggles and vision, but it took me years to be ready to make this film. Before I could start, I needed a clear grasp of my grandmother’s impact, both positive and negative, on my personal life. At first, I had only my intimate childhood memories. Now, having completed my own journey of 10 years of extensive research, I feel able to present a balanced portrait of the public figure that was my grandmother. I’ve searched for Dorothea the woman through journals, diaries, family letters, negatives and footage, and expanded my understanding of her place in history and documentary photography through my conversations with scholars and artists. The resulting portrait is this film.

These days, everyone has a camera. What are we really seeing, trying to capture? As we enhance and alter photographs with elaborate techniques, I often wonder what Dorothea would say. Her images reveal her subjects with straightforward exactness. Her sense of the beauty in the unaltered truth of life stays with me. “See what is really there,” Dorothea always said. “Look at it. Look at it.”