Dr. Isaiah Walker explains the cultural importance of surfing and how Duke Kahanamoku was a champion of generosity, aloha and bravery during a complex time in Hawaiian history.

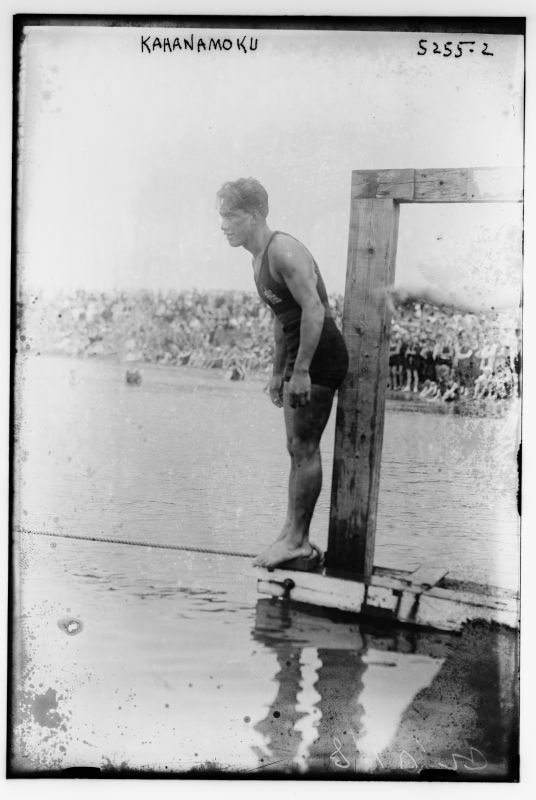

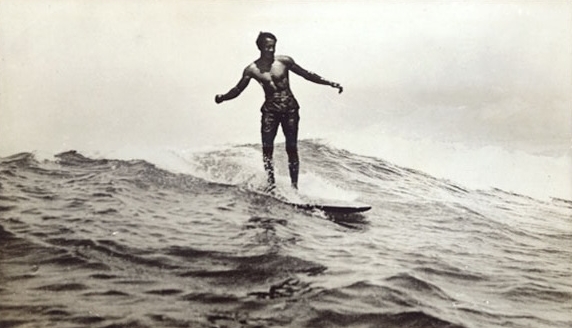

When reporters asked gold-medalist Duke Kahanamoku where he learned his signature swim technique, he explained that he inherited it from his kupuna (ancestors). Since Pacific Islanders were the great navigators of the ancient world who invented he‘e nalu (surfing), familiarity in the ocean has been an essential part of a Hawaiian identity. Like his ancestors, Kahanamoku spent most of his young life swimming, surfing, canoe paddling, fishing and diving. As seen in the life story of Duke Kahanamoku, many Native Hawaiians found solace in the ocean as a traditional sanctuary during a challenging time in their history. Because of this, surfing remains a prominent cultural identity marker for native Hawaiians today.

British voyager James Cook noted the comfort level of Hawaiians in ocean waves in 1779. He was dumbfounded by the sight of “young boys and girls of nine or ten years of age playing amid such tempestuous waves that the hardiest of our seamen would have trembled to face.”[i] His men also witnessed Hawaiian surfing firsthand and were amazed by it;

Lieutenant James King recorded, “they lay themselves at length upon their boards…their first object is to place themselves on the summit of the largest surge, by which they are driven along with amazing rapidity toward the shore. The boldness and address with which we saw them perform these difficult and dangerous maneuvers, was altogether astonishing.”[ii]

Historian David Malo called surfing a national pastime in old Hawaii, practiced by men and women of all ages and ranks. Although some Christian congregations later frowned on surfing, Hawaiians continued to surf in the 19th century. For some, the ocean waves became an escape from the hardships of that century, most notably the drastic depopulation of Hawaiians by foreign introduced diseases and the eventual overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

“The Kahanamoku family relocated, in part, to escape the political unrest in Honolulu . . .”

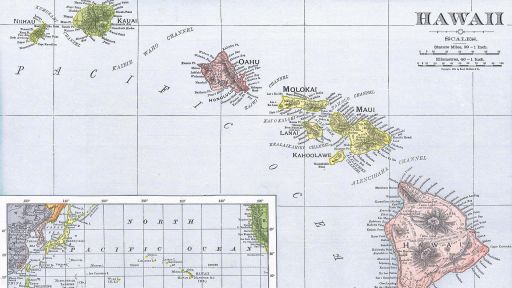

In January 1893, when Kahanamoku was two years old, a disgruntled small group of white businessmen with the unauthorized backing of Honolulu stationed U.S. Marines (led by John L. Stevens), staged a coup to overthrow the Queen of Hawaii. Their plan was to overthrow the government and turn it over to the United States, ultimately benefiting their sugar business and the prominence of the U.S. Military in the Pacific. However, since Hawaii was an internationally recognized independent state, toppling the Hawaiian Kingdom proved difficult to legally accomplish.

The coup d’état government planned to topple the Hawaiian Kingdom with a treaty of annexation to the United States. However, President Grover Cleveland’s condemnation of this action did not help the cause. While Hawaiians were successful at killing annexation attempts with petitions and protests in the mid 1890s, the tide turned against the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1898. The outbreak of the Spanish American war sparked the new and openly imperialistic McKinley administration to occupy Hawaii without a formal treaty or agreement. Instead, they claimed Hawaii with a domestic bill in congress, essentially disregarding both U.S. and international law. Native Hawaiians were overwhelmingly opposed to and disheartened by this.

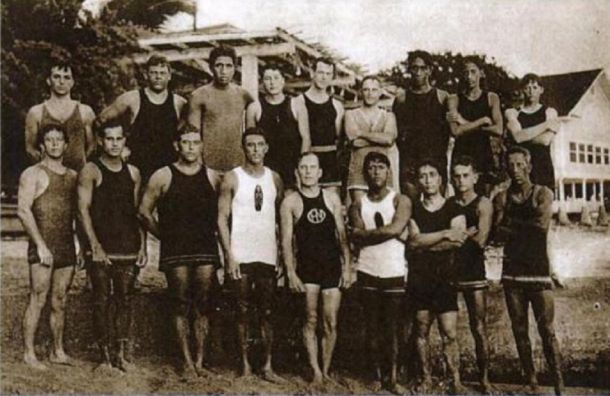

The Hui Nalu, Club of the Waves, founded in 1908 by Native Hawaiians in defiance to their exclusion from haole (Caucasian) The Outrigger Canoe and Surf Clubs. Duke Kahanamoku (back row, third from right).

Amidst this turmoil, the Kahanamokus moved from Honolulu to Waikiki on Duke’s maternal family land in Kalia. The Kahanamoku family relocated, in part, to escape the political unrest in Honolulu and to be closer to the ocean. Since the ocean was an overlooked realm to colonial entities, it was a place where Hawaiians, like the Kahanamokus, could feel at home, at ease, and in charge. They were still chiefs in the surf. But this Hawaiian realm did not go unchallenged.

In 1908, pro-annexationists and racial segregationists opened a whites-only surf club in Waikiki. The Outrigger Club was not well-received by Hawaiian surfers at that time, and tensions in the ocean escalated over a contested Hawaiian realm, the po’ina nalu (surf zone). In opposition, Kahanomuku and his many brothers, cousins and friends formed a rival club called Hui Nalu. This surf club was open to all races and sexes, but was led by native Hawaiians. One of its most prominent members was Prince Jonah Kuhio, first to introduce surfing to California in 1886 and heir to the Hawaiian kingdom throne. The battle between these two clubs was essentially an overspilling of the political turmoil faced on land, involving many of the same individuals, but with a very different outcome. Ultimately, these Hawaiians asserted their dominance in the waves and maintained their social standing in the ocean.

“Though he was soft-spoken on land, [Duke Kahanomuku] was a showman in the surf.”

Duke became a famous swimmer after breaking the world record in the 100-meter sprint and then earning his first gold medal in 1912. Native athletes led the U.S. team in the early 1900s; Native American Jim Thorpe (of the Sac and Fox Nation) dominated in land sports and Kahanamoku in swimming. But as Kahanamoku traveled the world en route to decades of Olympic games, he became a phenomenon at his surfing exhibitions. Australia, New Zealand, New Jersey and many other shores hosted Kahanamoku’s surfing exhibitions. At each locale, he was cheered by throngs of spectators as the Hawaiian celebrity who walked on water. Though he was soft-spoken on land, he was a showman in the surf. This was also true of his crew in Waikiki, as Kahanamoku and his Hui Nalu peers also moonlighted as Waikiki beachboys: surf instructors, entertainers and beach celebrities in the early years of Hawaii’s tourism.

Kahanamoku’s life story is a mix of triumph and hardship. Despite his fame, he often struggled financially. His Kalia Waikiki family oasis transformed before his eyes, from a Hawaiian ocean village to hotel development and a U.S. Army R&R center called Fort DeRussy. Although he had wealthy and influential friends, like American billionaire tobacco heiress Doris Duke, who helped him secure a residence on O’ahu, he was dampened by the possibility of losing his Olympic medals for employment related to swimming.

Kahanamoku found work appearing in Hollywood films. However, despite being an icon of Hawaiian masculinity, he was often eclipsed by Hollywood heroes in these films. For example, in the 1954 film “Wake of the Red Witch,” John Wayne’s character, Captain Ralls, does what Kahanamoku’s character is unable to do: swim deep underwater to kill a sinister giant octopus. Kahanamoku’s character then rewards Ralls with the island’s greatest possession, a large chest of pearls. Although entertaining to some, Hawaiians recognize such representations of Kahanamoku as pure fiction.

Sadly, in the real world, some have used Kahanamoku’s popularity for their own financial benefit. Eventually, his own name was trademarked and used by others for financial gain: through a chain of restaurants, clothing brands and the general use of his name, image or likeness.

Although he was successful in breaking many color lines, racism still had a prominent impact on Kahanamoku, who often struggled to find balance in that world. Perhaps because of this, Kahanamoku longed to return to old Hawaii, nostalgic for a traditional lifestyle. However, to the native Hawaiian, Duke Kahanamoku remains uneclipsed. He is an icon, an empowered kanaka (person) and our champion (moho). Although Duke has been marketed as a mascot of Hawaiian generosity and aloha, he is also a powerful Hawaiian warrior who navigated a challenging time in our history.

[i] J.C. Beaglehole, ed., Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery, 1776-1780 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), excerpt from Samwell’s Journal, 1165.

[ii] James King, A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, Volume III 1779-1780 (London: W. Stranhan, 1784) 146-147.