Duke Kahanamoku changed the world with his athletic accomplishments, from competing in the Olympics to revolutionizing lifesaving techniques in the water. The following is based on a discussion guide created by The Foundation for Global Sports Development.

1. Inventing the “Kahanamoku Kick”

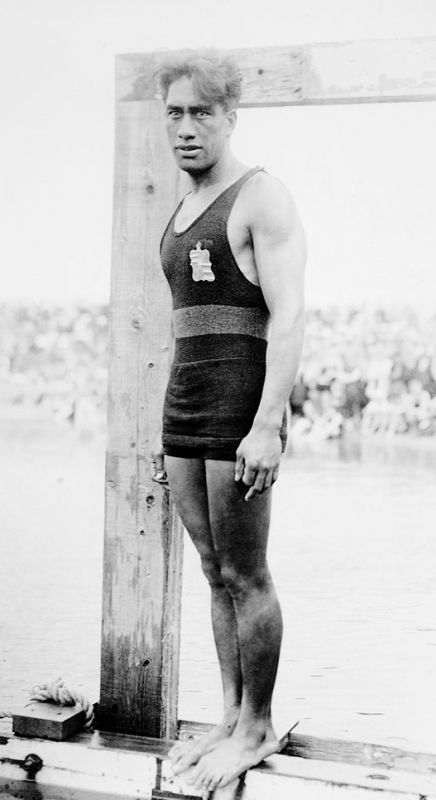

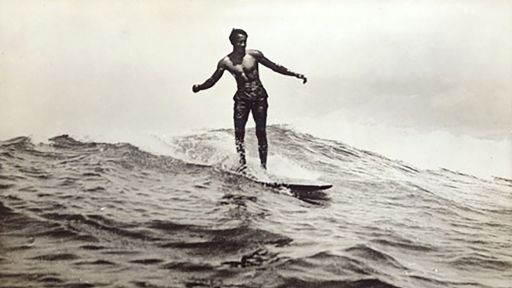

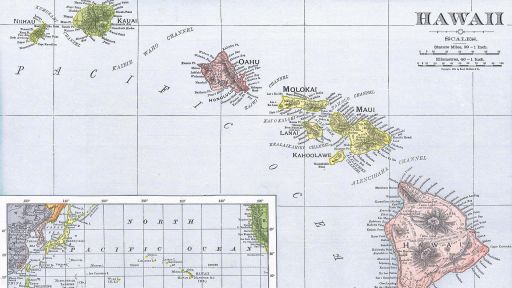

Having grown up with the ocean as his backyard in Hawaii, Duke Kahanamoku became a skilled swimmer and surfer. In addition to being raised around the water, his physique made him a natural athlete particularly suited to swimming. Kahanamoku stood six feet, one inch tall and is said to have had size 13 feet, which combined with the double-flutter kick he was taught since childhood, propelled him through the waves. Later dubbed the “Kahanamoku Kick,” he used his variation of the Australian crawl in freestyle swimming events to easily beat the competition. His feet were probably also a phenomenal asset in surfing, helping keep his weight more evenly distributed over the board and most likely making his elegant, upright stance easier to maintain. Kahanamoku often competed in friendly canoe and swim races, but there had never been an event recognized by mainland sporting governing bodies on the islands until a few weeks before his 21st birthday.

2. Winning Hawaii’s first swimming competition

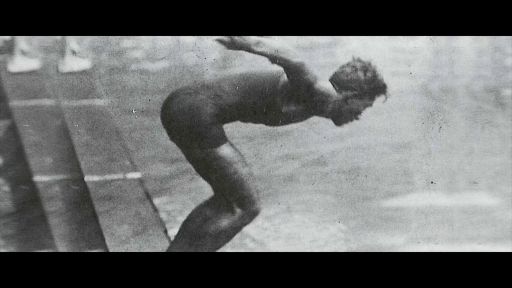

On August 12, 1911, Kahanmoku participated in Hawaii’s first American Athletic Union (AAU) sanctioned swimming competition, and handily took first place shattering the 100-yard freestyle world record by 4.6 seconds, and the 50-yard by 1.6 seconds. The AAU found his race results so implausible that they disallowed the record-setting times and attributed them to factors unrelated to his skill, such as the currents in Honolulu Harbor and timekeeping errors. The people of Hawaii rallied around Kahanmoku and raised the funds to allow him to travel to the mainland in February of 1912 to prove his swimming ability to the AAU authorities. He arrived in Pittsburgh and had a disastrous showing in his first pool competition, the 220-yard national championship race, needing to be rescued from drowning when his muscles cramped up. He tried again later that week with a couple of exhibition races—the 50-yard and the 100-yard—winning both and impressing George Kistler, who coached at the University of Pennsylvania. Kistler offered to help Kahanamoku improve his diving, breathing and turning.

3. Winning for the U.S. Olympic swim team

The work paid off when Kahanmoku made the U.S. Olympic swim team less than a month after his arrival. Kahanamoku went on to win a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle and a silver medal in the 4×200-meter freestyle relay at the Stockholm Olympics that summer, becoming a worldwide sensation and one of the most popular athletes at the Games.

Just one year after that fateful race in Honolulu Harbor, Kahanamoku celebrated his twenty-second birthday by participating in a massive victory parade for the American Olympic team in New York, where he was showered with confetti and ticker tape. Kahanamoku spent the next four years training for the 1916 Summer Olympics scheduled for July in Berlin, Germany. With World War I raging, the Games were eventually cancelled by the host country in March of that year, leaving Kahanamoku to wait and train another four years before defending his title as reigning champion. He spent eight months in 1918 touring the U.S. to raise money for the American Red Cross by giving swimming, diving and lifesaving performances with fellow Hawaiian swimmers Clarence Lane and Harold Kruger, until he contracted the Spanish Flu in Washington D.C. during that year’s deadly pandemic. Kahanamoku recovered and regained his strength and fitness by training to come back to the world stage.

He went on to compete in two more Olympics, Antwerp and Paris, accumulating a career total of three gold and two silver medals. He set world records in the 100-yard freestyle three times from July 2013 to September 1917, bettering his previous number each time, until he got it to 53 seconds, a record that stood until Johnny Weissmuller broke it in 1922. His stint in Hollywood, where he hoped to make it big, only led to bit parts since he couldn’t be featured swimming in the movies without losing his Olympic eligibility and he wasn’t given leading man roles because of his race. Even later in life when his name and likeness were used to promote the Aloha Shirt, he saw few of the royalties the company collected.

4. Duke Kahanamoku’s impact on Hawaiians and Pacific Islander athletes

In 1999, Surfer Magazine named Duke Kahanamoku “Surfer of the Century.’’ His posthumous recognition continued the following year when Sports Illustrated dubbed him the “greatest sports figure of the century” from Hawaii. His impact on the world went beyond his own athletic accomplishments and the sports that developed as a result. He inspired people all over the world to follow their own sports journeys, but his impact as a source of pride for generations of Hawaiian and Polynesian athletes who would follow in his wake was particularly significant. Kahanamoku helped Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders reconnect with their heritage and cultural identity. As the best swimmer in the world during his prime and a legendary surfer, Kahanomoku made waterman skills aspirational, not something to be ashamed of like many had grown up hearing. He proved that traditional activities like fishing and surfing had value and were admired in Hawaii, and now, around the world. Polynesian athletes have Duke Kahanamoku to thank for breaking through the barriers of racism and segregation that Pacific Islanders had faced in sports. At Duke’s funeral service, award-winning radio broadcaster Arthur Godfrey delivered his eulogy stating, “[Kahanamoku] gave these islands a new dimension, winning the respect of the world for himself and his people. What Longfellow’s Hiawatha and later Jim Thorpe had done for the American Indian, [Kahanamoku] did for all Polynesians, especially Hawaiians.”

5. Revolutionizing lifesaving techniques

Like the sports born from Kahanamoku’s showcasing of surfing, modern lifesaving techniques are a direct result of his expertise in the water. Beyond the countless people he personally saved during his lifetime, he saved untold more by proxy since he gave rise to the widespread use of rescue boards and helped lifeguarding become a profession. “The Science of Beach Lifeguarding” by Mike Tipton and Adam Wooler credits Duke Kahanamoku as the source of the introduction of the “rescue board” to lifeguarding practices. In 1912, one of the Australian lifesaving clubs acquired a surfboard while in Hawaii in hopes of incorporating it into their lifesaving repertoire. However, upon their return, they were unsure how to use it to its full potential. In 1915, during a visit to Australia, Kahanamoku taught the Australian lifesavers the most effective use of the boards. The utility of surfboards as rescue devices became evident in 1925 when he witnessed a 40-foot sport fishing vessel get hit by a squall and capsize from the beach at Corona del Mar in Newport Beach, California. He instinctively swam out with his surfboard, making over eight trips through the stormy chop to the overturned Thelma, hauling passengers onto his board, and eventually saving eight people while other surfers rescued an additional four. Kahanamoku then went back to recover the bodies of those who didn’t survive. Newport’s police chief at the time called Kahanmoku’s efforts “the most superhuman surfboard rescue act the world has ever seen.” U.S. lifeguards began using surfboards in water rescues because of this incident.

6. Duke Kahanamoku’s impact on board sports

Nearly every board-riding sport we know today was inspired by Hawaiian surfing, and the evolution can be traced back to Duke Kahanamoku. As he showcased surfing around the world, those who took up the sport developed more ways to experience the thrill of surfing not just in the water, but on snow, dry land and even in the sky, leading to the birth of skateboarding, snowboarding and many other variations.