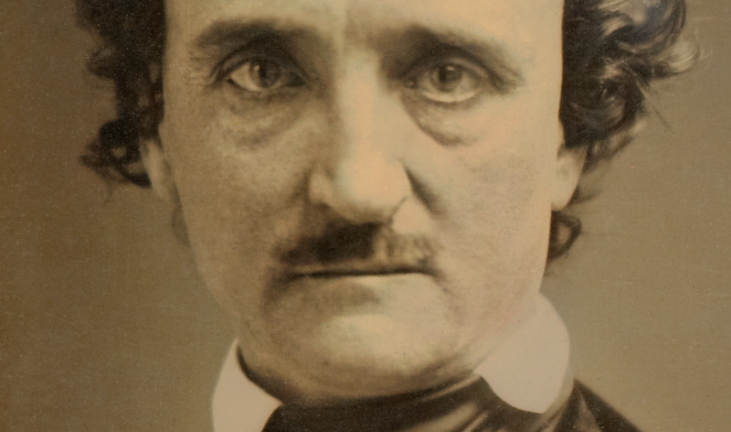

“In biography the truth is everything.” — Edgar Allan Poe

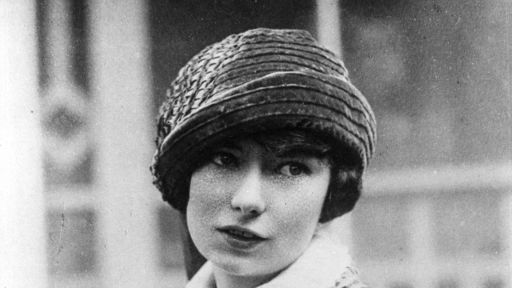

Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, January 19, 1809, the son of two actors.

By the time he was three years old, his father had abandoned the family and his mother, praised for her beauty and talent, died due to complications from tuberculosis. Her death was the first in a series of brutal losses that would resonate in Poe’s work throughout his life.

Poe was taken in by John Allan, a wealthy Richmond merchant and an austere Scotsman who believed in self-reliance and hard work. His wife, Frances, became a second mother to Poe until she died in 1829. Allan, who had never formally adopted Poe, became increasingly harsh toward him, and the two clashed frequently. By the time he was 20 years old, Poe left the Allan home, vowing to make his way in the world alone.

After abandoning a military career —during which he published his first book of poetry— Poe landed in Baltimore and took refuge with his aunt, Maria Clemm, and Clemm’s 13-year-old daughter, Virginia, whom he would later marry despite their significant age difference. While in Baltimore, he won a newspaper contest with the story “MS. Found in a Bottle” and found his first literary success. His Baltimore connections led to a job in Richmond as the editor of a literary journal, and his career as a “magazinist” and literary critic was launched. Poe believed strongly that the United States should hold the arts —particularly writing— to exceptionally high standards. His harsh reviews brought him the nickname the “Tomahawk Man” and also earned him many enemies.

During the 1830s and ’40s, Poe moved between Philadelphia and New York as an editor and contributor to some of America’s most popular magazines.

He worked with equal skill in poetry, short stories, non-fiction, essays and works of social and literary criticism; during this time he also published his only novel. Poe is often credited for having invented the modern detective story and for creating the science-fiction genre as well. Poe achieved arguably his greatest triumph in 1845 when his poem, “The Raven,” was published to great acclaim. It is often billed as the most famous poem in American literature, and for a time the poem made him a celebrity.

Despite his success, Poe remained impoverished and all but destitute.

He not only played the tortured artist, he lived the part. At times he drank heavily and behaved erratically. He suffered no fools and offended many. As more than one biographer has noted, Poe had a remarkable knack for undermining himself whenever success came too close. After the publication of “The Raven,” at the height of his fame, he gave a reading in Boston during which he insulted that city’s literary establishment – many of whom were present. Scandal ensued.

In 1847, his young and beloved wife Virginia died of tuberculosis. Her death drove Poe into a deep depression. In a revealing letter to a friend, he wrote of how Virginia’s repeated oscillations between recovery and relapse had driven him “insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

In 1849, during a period of recovery and relative optimism, Poe traveled the east coast, working toward achieving his dream of starting his own magazine, The Stylus.

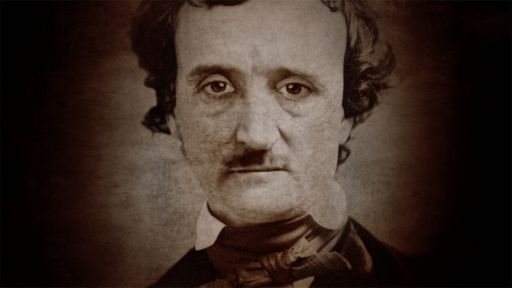

Though he was reportedly ill, Poe arrived in Baltimore in late September 1849 on the eve of a raucous and corrupt municipal election. He mysteriously vanished for five days. When he reappeared he was delirious and wearing clothes not his own. He never regained his senses and four days later, on October 7, 1849, died soon after uttering the name “Reynolds.” The creator of the modern detective story died at the heart of his own mystery.

Major support for Edgar Allan Poe: Buried Alive is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Additional support for this film is provided in part by National Endowment for the Arts, Joy Fishman, and Wallace S Wilson.