Painter Edward Hopper’s visions of solitude, light and space have uniquely imprinted on American culture. His body of work continues to be reimagined through other artists and many filmmakers have used Hopper’s paintings as a visual springboard within various genres. In Hopper’s lifetime, the relationship between his work and pop culture was reciprocal – Hopper not only influenced cinema, but was also artistically inspired by the movies he saw.

Painter Edward Hopper’s visions of solitude, light and space have uniquely imprinted on American culture. His body of work continues to be reimagined through other artists and many filmmakers have used Hopper’s paintings as a visual springboard within various genres. In Hopper’s lifetime, the relationship between his work and pop culture was reciprocal – Hopper not only influenced cinema, but was also artistically inspired by the movies he saw.

Edward Hopper and the movie theater

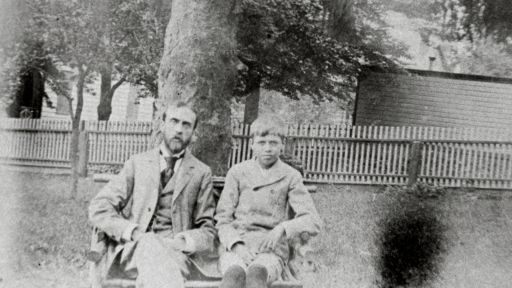

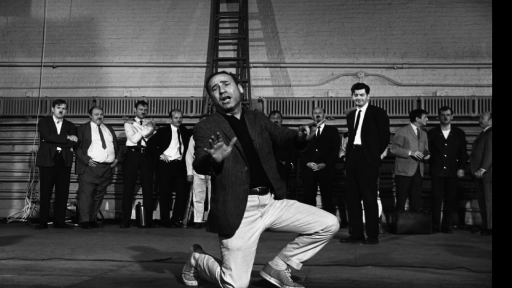

Edward Hopper is often considered part the Ashcan School, an artistic movement founded by Robert Henri – one of Hopper’s instructors at the New York School of Art and Design. The Ashcan artists explored scenes of New York City’s daily life, embracing the cultural, social and economic changes of the early 20th century. Among these various social shifts was the advent and popularization of film, which had emerged as its own artform and pastime. In keeping with the spirit of the Ashcan philosophy, Henri encouraged Hopper to go to theaters as an exercise in observation.

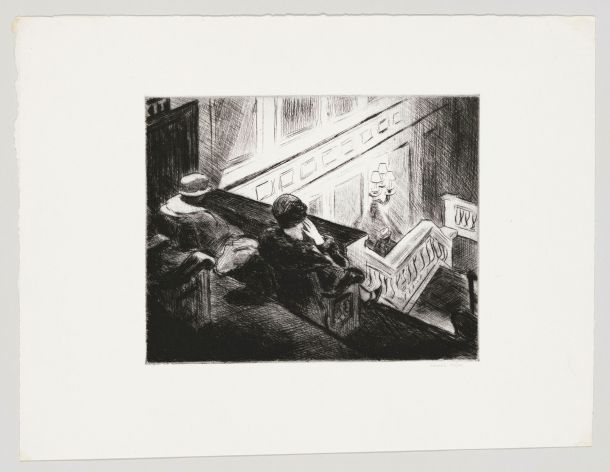

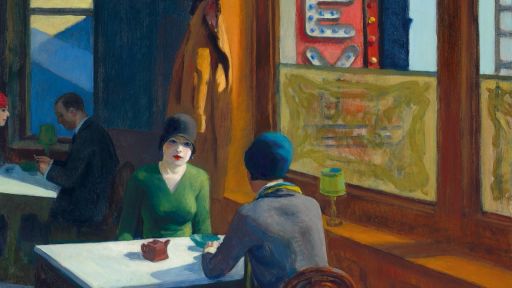

The movie theater would become an integral part of Hopper’s life – a place of quiet reflection and refuge from his studio. Etchings of theater observation included pieces like “The Balcony,” but Hopper’s work would not reflect the on-the-ground realism of the Ashcan School. Encapsulated in his famous painting, “New York Movie”(1939), Hopper was fascinated with the space of the theater in relation to the individual, not the crowd. In this image, an usherette stands alone off to the side of an aisle, her face partly obscured. Director Sam Mendes (“Spectre,” “American Beauty”) said, “In ‘New York Movie’ . . . the lighting of the scene is absolutely the source of its poetry . . . You begin to invent your own story from the imagination [depicted] in the world of the painting.”

As Philip French writes in The Observer, Hopper was interested in the “isolation of individual spectators waiting for the curtain to go up or the lights to go down.” Hopper’s version of the movie theater goes against the idea of it as a communal experience. He would later reject his inclusion in the Ashcan movement, claiming his New York had “not a single incidental ashcan in sight.”1

Hopper and the film noir genre

Born in 1882, Hopper grew as an artist while the film industry blossomed. His relationship to the medium was further reinforced by his early work as an illustrator for silent film posters and pulp magazines.

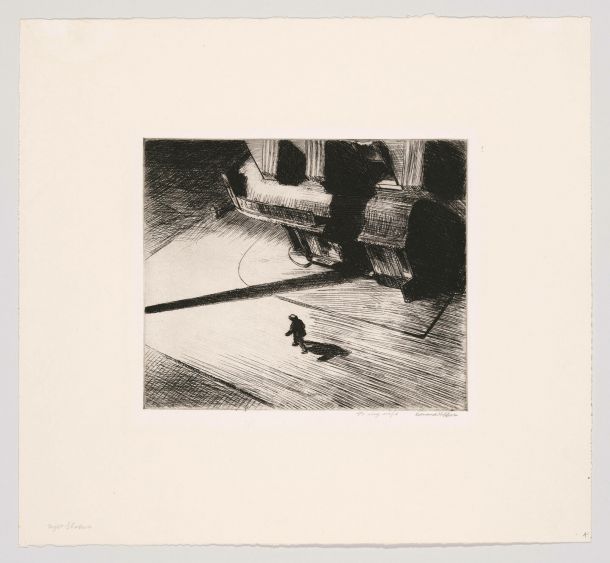

Early in his career, Hopper experimented with perspective. While the Ashcan artists typically framed point-of-view from the street level or directly within a scene, Hopper’s paintings were often removed from the action, positioned at elevated or distant viewpoints. The observer in a Hopper piece is one outside of daily life, not part of it.

His etching “Night Shadows” (1921) is an example of this voyeuristic sensibility, likely influenced by European film. In this piece, you see the visual language of the movies take shape in Hopper’s artistic choices, echoing the cinema overseas with stark camera angles, harsh lighting, exaggerated contrasts (chiaroscuro), distorted spaces and dark urban settings – features which would later become characteristics of the film noir genre.

Noir is “characterized by a mood of cynicism, fatalism, menace, and moral ambiguity”2 popular in the 1940s and 50s. It drew inspiration from German Expressionism, such as the work of Fritz Lang, director of “Metropolis” (1927) and “M” (1931) – often considered film noir precursors. You can see Hopper-like qualities particularly in the production design for “Metropolis.” Re-imagining Manhattan, “Metropolis” combines various art movements and architecture, like Art Deco, Bauhaus and Italian Futurism. Whether intentionally or not, Hopper’s work also seemed to explore the interests of these movements, looking at the way buildings interact with individuals.

Unlike Norman Rockwell, Hopper didn’t use photos as part of his creative process, but created realist work based on the ideas of places, interactions or sights. The cityscapes of Hopper’s work are not bustling locations, but depict a quiet stillness. Much like “Metropolis,” the New York in Hopper’s paintings is indistinct, as if capturing the concept of the city as an abstraction of America, rather than replicating life in the way the Ashcan artists might have aimed to. Hopper would go on to create a body of work exploring American life and locations, drawing inspiration from both observation and fiction.

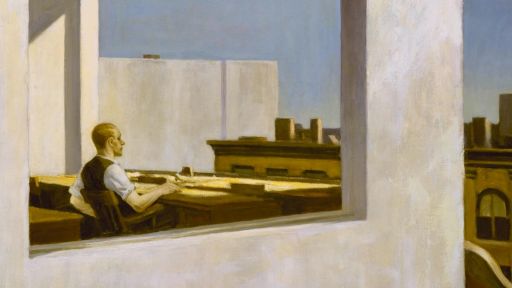

Hopper spent days at the movie theater and by the 1940s, he was actively consuming noir film, incorporating its themes into his paintings and influencing the genre himself. In particular, the dim offices of noir filled with angular shadows are reminiscent of his paintings like “Office at Night” (1940) and “Office in a Small City,” in which simultaneous interior and exterior perspectives create distortion. Windows and mirrors are also a motif in both noir as a genre and Hopper’s work, with compositions framed through these devices. Like many noir films, Hopper’s figures are often solitary, and his work never included children.

Throughout his life, Hopper discussed the movies he saw. In 1962 he wrote, “If you want to know what America is all about, go and see a movie called ‘The Savage Eye.'”3 This 1959 film, which combines dramatic fiction with documentary material explores the dark side of 1950s urban life, following a woman through the streets of Los Angeles across various locations. Though he may have rejected the Ashcan school, Hopper similarly explored popular culture of America through everyday urban locations like offices, diners, gas stations and hotels.

Hopper’s influence on movies

Of the auteur directors inspired by Edward Hopper during his lifetime, the work of Alfred Hitchcock (following his move to the United States in 1939) is noticeably in conversation with Hopper’s work. Adam Weinberg (Director, Whitney Museum of American Art) said:

“. . . if you look at movies like ‘Strangers on a Train,’ which is early Hitchcock. . . you see influencing [Hopper]. And then you see [in] later Hitchcock with something like ‘Psycho,’ which Hopper was very amused about actually, where Hopper had influenced Hitchcock.”

Famously, Hitchcock referenced Hopper in “Psycho” (1960), and used the painting “House by the Railroad (1925)” as a basis for the Bates mansion. Similarly, other films like “Rear Window” (1954) and “Shadow of a Doubt” reference Hopper’s work.

Other directors to reference Hopper in their work include David Lynch (“Blue Velvet,” “Twin Peaks) and Ridley Scott, who is rumored to have kept a copy of “Nighthawks” on the set of “Blade Runner” (1982), stating: “I was constantly waving a reproduction of this painting under the noses of the production team to illustrate the look and mood I was after.”

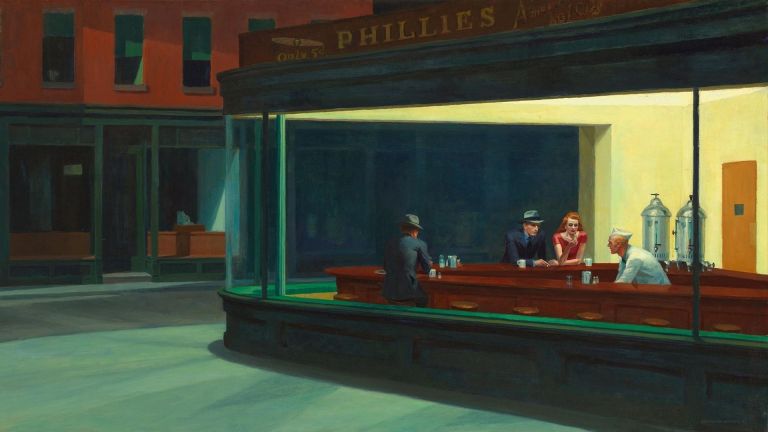

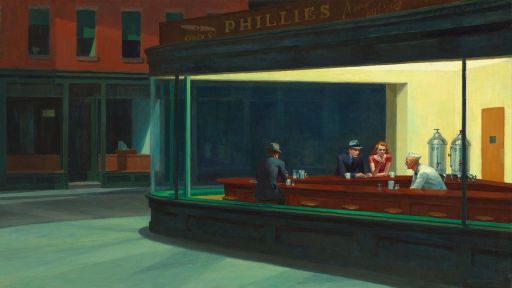

German director Wim Wenders (“Perfect Days,” “Paris, Texas”) once said that “All the paintings of Edward Hopper could be taken from one long movie about America, each one the beginning of a new scene.” Similar to Hitchcock, whose work seemed to be influenced by Hopper once working in the United States, Wenders has frequently cited Hopper as a muse. When creating “Paris, Texas” (1984) Wenders explored American culture through the story of a road trip, drawing inspiration from Hopper’s work for the thematic and visual approach. In “The End of Violence” (1997), Wenders featured a scene tribute to Hopper’s most famous painting, “Nighthawks” (1942).

“Nighthawks” is perhaps the most representative of Hopper’s reciprocal relationship to film and storytelling. One of the most recognizable paintings in American art, the scene has served as inspiration for many directors and writers. Although loneliness is often attributed to the painting, Hopper often protested the theme and was reluctant to ascribe meaning to his work. But in rare response to a query about “Nighthawks,” Hopper once admitted that “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.” Much like the German Expressionist work, Hopper’s painting emphasizes the architecture more than the people.

The diner in “Nighthawks” feels like the concept of a diner, but the visuals don’t make complete logical sense. Art curator Carol Troyen describes the uneasiness of the image:

“. . . the longer you look, the more puzzling it becomes. And it’s not only ‘what are those people doing there in the middle of the night?’ There are no signs on the windows identifying the establishment. There’s no door. There is no way to join the people in that diner. And I think its attraction has to do with that enigmatic quality.”

Art historian Gail Levin suggests that the painting was inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Killers” about two hitman in a 24 hour diner. When “The Killers” was adapted into a movie by director Robert Siodmak in 1946, he directly referenced “Nighthawks” in composition.

Levin believed that Hopper’s interest in “The Killers” was the “suspense of impending violence that never takes place,” much like Hopper’s paintings themselves.4 What makes Hopper’s work feel cinematic is its ability to capture moments in between action, as if the scene is one just before or after an event. It’s this injection of narrative into the art that continues to serve as an inspiration for filmmakers.

Work Cited