TRANSCRIPT

(bright expectant music) - It's been said that until an artist has painted it, an environment remains barren.

Now, the art of Mr. Edward Hopper represents a major conquest of the American scene, especially the town and city.

And after seeing his art, America is changed.

Now, to change a whole area of experience for us is no small achievement.

Mr. Edward Hopper has done that with a strictly honest tenacity, over a lifetime, in pictures such as this, which achieve a tremendous impact.

This one's called "Early Sunday Morning", It's done in 1930.

And as we look at it, it's laden with meaning.

And it's this ability of his to weigh the simplest facts with meaning that makes his art great.

It's perhaps a quality of stillness that keeps us watching, as if we were anticipating its interruption.

And the street with its calming horizontals is empty, except for that curious dialogue of its only two inhabitants, the barber's pole, the hydrant that you're looking at now.

There's the barber's pole.

And again, they, through intense concentration and isolation, they arrest our eye and invite us to fill that sense of meaning that they give us with speculation.

And the same thing happens in the windows.

They're at first sight, not very different from each other, but then one notices the most inventive variation in the windows.

Some are only a quarter drawn with blinds, others are half-blinded, and some are fully drawn.

And again, they invite speculation, which leads one off into many associations, but to follow them destroys the essence of the picture.

Now obviously, what we've got here is something that can only be stated visually and no other way.

It's a quality that makes Edward Hopper one of the purest of American painters.

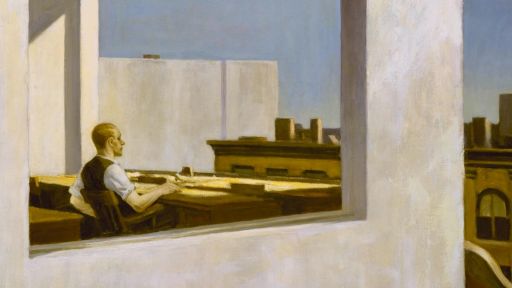

And here again a scene, casual, unpopulated, in which the shapes of the prosaic are isolated, accented, and transcended.

It's again the long horizontals, this time so arranged that there's a converging movement to the left to catch the end of a train disappearing behind the wall.

Mr. Hopper's pictures often bring one's thoughts into the area outside the picture, outside the immediate frame of reference, so that his work gives one a sense of isolation and vastness.

And also behind its immediate solidity is, I think, a sense of the transitory.

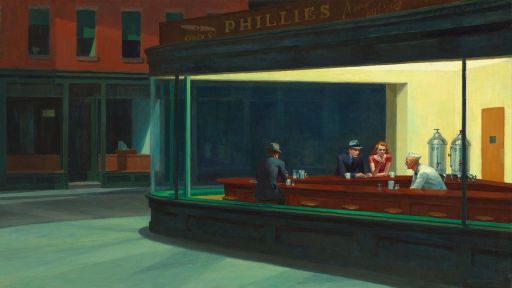

Perhaps that's more obvious in this picture, painted in 1942, called "Nighthawks".

And a great deal has been said about the isolation of the people in his pictures, however, the people he introduces into his pictures, they don't seem oppressed by that loneliness.

They're anonymous types of humanity for the most part, and their outstanding characteristic, well, it seems to be a certain heedlessness, a submission.

It's not they who are most important, even in this picture.

It's the steady fall of brightness on the lighted wall to the right that turns this into art.

And the mood is in the light rather than the people, and it's also in the hypnotic, empty streets with their haunting facades.

Light and atmosphere, creating with great clarity and exactitude a palpable mood, which, when you try to define it, escapes you.

That's very much part of the art of Mr. Edward Hopper.

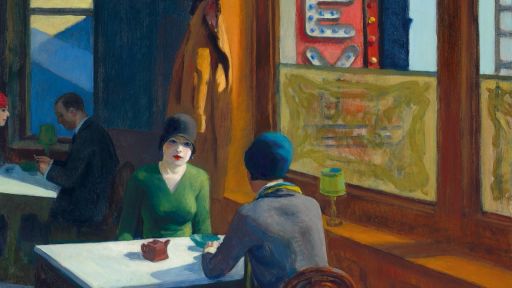

And this picture's called "New York Cinema", and was done in 1939, although dates, like titles, are not very important, for the essential quality of work hasn't changed.

He's only learned to hold that quality, as time goes on, more firmly.

And the tawdry baroque magnificence of the cinema has never been more specifically expressed, or indeed, the bored indifference of the usherette.

Arrivals, departures, and the clarity of light that underlines perception for a few minutes at dawn and evening.

These are the things that Mr. Hopper's very conscious of.

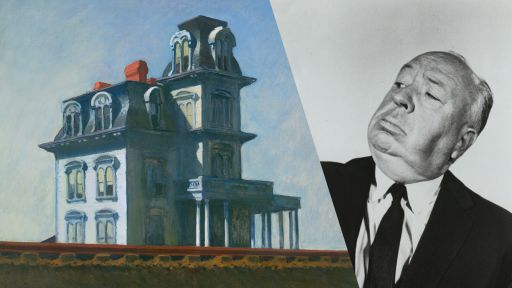

And here's one of his earliest classics, "House by the Railroad".

The railroad's in the foreground, you can see it there.

Again, you see there's the sense of passage and transience, literally here underlining, literally, the fact of the house's instant and immensely solid perception, like something glimpsed from a train in passing.

Now, the strict control and understanding of what he paints gives immense eloquence to even the slightest gesture in his pictures.

And a gesture may be even a patch of sunlight, or a curtain sucked through a window by the wind.

Now this, as we look at it, is infused with the deepest meaning for us, in a way that strikes one as being so translucently simple, that we keep searching for complexities.

And indeed, such clarity does have many undertones.

And such slow and gathering intensity represents in each picture the result, Mr. Hopper tells me, of an intense creative struggle, and these pictures come slowly, and they come with difficulty.

And indeed, they form perhaps the most subtle and indivisible inter-penetration of form and content in American painting.

As the associations his pictures provoke, he leaves them open.

And by stating them, as many critics have, something wordless and visual in his paintings is destroyed.

Now, Edward Hopper had a long struggle for recognition before that historic exhibition of his watercolors in the Rain Gallery in 1934.

He developed slowly but with a direct and gathering strength.

Now, there's no doubt that today, he is recognized as one of America's immortals in painting, and I'd like you very much to meet him.

Well, Mr. Hopper, you came up here by plane.

- That's true, I did.

- [Brian[ You don't you like flying, do you?

- No I don't, I'm afraid of it.

- You're afraid of flying.

I guess many would say- - Afraid to die that way.

- That way, yeah.

Well I think, there's one of the rules of television, you know, they should never sort of say thank you to a person formally, "Thank you for being here," that sort of thing.

But I think rules are made in many ways by breaking them.

And you sir are 78, isn't it?

- That's true.

- And I want to tell you that you do us great honor by being here.

- Thank you.

- And Mrs. Hopper was with you, and whom you'll meet later.

Well, you mentioned that your pictures come very slowly.

- They do.

- And perhaps you could tell me something about that.

- Well, it's very hard to define how they come about, but it's a long process of a gestation in the mind and a rising emotion, I suppose.

But they finally come, perhaps not more than one or two a year, but maybe that's enough, better than a great many, not so good.

- [Brian] Yeah, well do you think about them a long time before you actually paint?

- I do, and I make various small sketches, sketches of the thing that I wish to do, also sketches of details of what I need in the picture, and that's how it comes about eventually.

- You said it's the result of many impressions.

- That's true, combined.

- So strictly speaking, many of the pictures are not scenes, actual scenes, actual places?

- Very few anymore.

There was a time when I worked directly from, I call it the fact, some call it nature.

But I do that very seldom now, they're almost all improvised.

- [Brian] Do you do many drawings for them now?

- Yes, many drawings.

Quite often, many drawings.

- Well, about the content of your pictures, I think that some people have seen a lot of psychological elements in it.

Loneliness, isolation, modern man and his manmade environment.

How do you feel about that, do you think that's true?

- Well, I think that's, those are the words of critics.

And I can't always agree with what the critics say, you know?

It may be true and it may not be true.

It's probably how the viewer looks on the pictures, what he sees in them, that they really are.

Could that be?

- I guess it could be.

What do you think is the content of your pictures?

What's your main interest in painting them?

What do you think makes you choose this particular furniture in the picture, that's become so very much Hopper furniture, as it were.

You know, the empty street, the frontage of the house, the dark woods, very often mysteriously in right or left.

What is it that attracts you in those?

Because you have a particular landscape that you've made your own.

What's drawn you to it, have you any idea?

- Well, I suppose it's just me, but I would like to say what Renoir said, that the important element in the picture cannot be defined, cannot be explained, perhaps is better.

That's the way I feel about it.

- You don't feel there's very much future in talking about painting, you just- - What?

- You don't feel there's very much future in talking about painting, you just go ahead and do it.

- Well no, I don't.

- Yet you did feel a certain interest in illustration at one time, didn't you?

Earlier on.

The narrative element interested you, you illustrated a number of stories earlier on in your career.

- Well really, illustration really didn't interest me.

I was forced into it by an effort to make some money, that's all.

I really had no interest in it.

I tried to force myself to have an interest in it, but it wasn't very real.

- I remember once you told me that you read a story by Ernest Hemingway and you said, "I'd like to illustrate that."

- Oh, perhaps I did say that, and I thought I'd discovered Hemingway.

So I wrote to Scribner's, telling them how much I admired Hemingway, and that I'd made a great discovery.

And of course they had discovered him long ago.

- Yeah.

(chuckling) What other writers have interested you?

I think looking at your work, somebody like Dreiser, Theodore Dreiser, or perhaps Sherwood Anderson might have certain affinities, or common sympathies.

- Well, perhaps.

I think maybe they're a little too Midwestern for me.

I admire Emerson very much.

Of course he wrote no fiction, but it's all philosophy.

But I admire him greatly, and read him quite a lot, read him over and over again.

- Well, let's get back a moment to the actual paintings.

The content many people find, is loneliness, isolation, that we've mentioned.

I don't think that, as you say, is your feeling.

What do you feel is the real content of your pictures?

What interests you in them?

- Well, I don't believe I can answer that question.

- How about light?

- Light?

Yes.

I'm interested in light, sunlight in particular.

- [Brian] And I think that that magnificent last picture you did, which we're looking at now, which is "Second Story Sunlight", the sunlight was the thing that interested you very much, wasn't it?

- Yes.

I attempted to paint a white sunlight rather than yellow, which many painters drop into the habit of painting sunlight as yellow, and sunlight isn't really yellow, except perhaps early in the day and late in the day.

Otherwise, to me it has a white quality.

- Sunlight.

- Yes.

- Many of your paintings have been just at that moment of early dawn, when things of a certain definitude and definition, and crispness of outline.

And many of them, then again, have the same atmosphere that you get from the starkness of sunset and the diminishing of light.

Have you ever painted very much or been interested very much in the full blaze of midday sunlight?

- Yes I have, and I've made several pictures of that character.

There's one called "High Noon", which is perhaps not a glaring success as sunlight, but it represents that time of day, at noon.

That picture is owned somewhere in the middle West.

I don't know just where, I've forgotten, by a private collector.

- Well now, when you mentioned "High Noon", it brings something to my mind, well, that includes Gary Cooper in it.

That was a movie that was made, and I mention movies because I know that you watch them a lot, you're very interested in them.

- Yes, I am.

- And I think it's the observant eye that interests you very much in them, from what you've told me.

For instance, I can tell that by dislikes, in a way, more than likes.

I mentioned to you the Swedish filmmaker Bergman, Ingmar Bergman, and you, how do you feel about him?

- I don't care for his work.

It's rather false and sentimental to me, and I don't really care for it.

But I like some of the French producers very much.

There's a picture produced recently that I would like much to see called "Breathless".

I haven't yet seen it, but I heard it's very fine.

- Well, moving from movies to paintings again, who are the, you know, we always talk about influences, I suppose.

And who do you feel means a lot to you as painters, and have influenced your art?

- Well, I don't think I really have any direct influences.

Of course, I admire some of the great ones, who most painters admire, Rembrandt, Degas, Courbet.

Courbet's landscapes rather than figures.

And most of the great French painters.

- What about the Americans?

I mean you have been, you know, you're so directly in the American tradition, according to every critic who writes, "Mr. Edward Hopper continues a tradition that goes back through Homer to Copley."

Do you feel that?

- I suppose that is true.

I admire Eakins very much.

I think he is a world painter, although he's not, has not that reputation as yet.

Perhaps he will be, have someday.

- [Brian] Do you admire Copley very much?

- His American period, yes.

- And what about Winslow Homer, that many have drawn parallel?

- Yes, I admire Winslow Homer.

- Well, in all those three that we've mentioned, Eakins, Homer, and Copley, there's a certain lack of rhetoric, and of the, sort of baroque gesture.

Is this something you object to, the artificiality in art?

Do you object to that very much?

- Yes, I do, I do.

You don't of course see it, in either Eakins or Homer or Ryder.

There is another painter who is perhaps not, hasn't the estimation that he should have, an American painter, and that's Homer Martin.

He wasn't always good, but some of his things are excellent.

- Well now, talking about artificiality in painting, you went to Paris as a young man early on.

You spent, I think you paid three visits- - Yes, I did.

- To Paris early on.

- I did.

- And this was certainly a very complex period, and one in which the artificiality of art, insofar as its elements and its organic elements were being juxtaposed and played around with a great deal.

And tell me something about the impression Paris had on you then, what it meant to you then.

- Well, I went to Paris at the time when the pointilist period was just about dying out.

But it had been taught to me a great deal, and I was somewhat influenced by it, because perhaps I thought it was the thing that I should do.

So the things that I did in Paris, the first things, had decidedly a rather modified pointilist method.

But later I got over that, and the later period things in Paris were more of an order of a kind of the thing that I do now.

- Who did you meet in Paris?

Did you meet many of the painters there?

- No, I met hardly any painters.

- No Picassos, no Braques, no- - No.

- No, how about the Americans?

- Well, I don't think I met any Americans that were of much importance.

- Well, when you came back to America from Paris, it must have been very difficult for you to try and come to terms with a whole new continent that hadn't yet in many ways been turned onto art, or at least not as you saw it.

- Well, it was.

Of course, it's a experience of most Americans who have been to Europe for the first time, that America seems very crude and raw, and unsympathetic to art, and it still is to some extent.

- What do you think, I think you have a quotation that is very close to your heart from Goethe, and I was going to ask you what you think, of what is most important to you in art, what art means to you, all those general questions that perhaps you might care to say something about.

- Well, this quotation is on literature, but it could easily apply to painting.

But I know that many contemporary painters will protest, and show the greatest contempt for this quotation.

But even so, I'm going to read it.

Goethe declared, "The beginning and the end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me, by means of the world that is in me.

All things being grasped, related, recreated, molded, and reconstructed, in a personal form and an original manner."

To me that applies to painting, fundamentally.

And I know there have been so many different opinions on painting now, that there will be many who protest that this is outmoded and outdated, though I think it's fundamental.

- That says it very eloquently.

Now, I think that anyone who knows the Hoppers, 'cause I'm here in the position of having come between husband and wife.

The Hoppers are really inseparable, and I think that we should ask Mrs. Hopper to remedy that and ask her to join us.

Mrs. Hopper is also- - Oh, sure.

- A painter.

Here is her painting of the Hoppers', the interior of the Hoppers' home in Cape Cod, which she sees the accidents of her immediate environment again and again with affection and strength.

What you're looking at now is a picture that Mr. Hopper painted of Mrs. Hopper many years ago, which is lucid and intense and affectionate.

And talking about that picture, Mr. Hopper, you know you sort of have been, you know, Mrs. Hopper, how do you feel about that picture?

Because what I'm going to say is this, Mr. Hopper is supposed to play down things in his pictures, play down the emotion.

Do you feel that that's an affectionate picture, that one he painted of you?

- Yes, when I recall things that he has done of people with double chins, and grabs right onto things they wouldn't like at all.

He didn't do that this time to me.

- [Brian] Yes, I think it's somehow tender in an austere way, quite effectively.

You trained as a painter with Robert Henri, didn't you?

- Yes, indeed.

- Do you think a lot of him?

- How could one not?

He's a great prophet of our age, I think.

He gave so generously to all of us, like the bird that plucks the feathers out of his breast for the young.

Well, he did seem to do that very thing.

- [Brian] Do you think he's a fine painter, Mrs. Hopper?

- Well, I think if you give it all away before you get to the easel, there's a little deficiency of what's- - He was a generous-hearted man.

- You have to go on with, you know?

- Yes, generous-hearted man, he was.

- Very, very, tremendously concerned with all of us.

Each one, he gave so much to them.

- What do you think of Henri as a painter, Mr. Hopper?

- I think he was moderately good.

- Oh.

- You don't agree with that, Mrs. Hopper.

- Oh, it's so ungenerous.

(Brian laughing) But you know, men are not grateful creatures.

- You think not?

- No, I don't think so.

- [Brian] Why do you say that?

- It's women that are grateful.

- Really?

I think- - And who cares, and who wants it, who cares about it.

- [Brian] Oh, I think you're a little hard on us, aren't you?

- Well, it seems to me that women are the ones that show the gratitude for little things and big, and who remember over the years, they remember.

- Yes, well now you have in many ways, been in the position of living with what is an American monument by now, although I don't know how Mr. Hopper would like to hear me describe him as that.

And have you found this difficult for your own painting?

- Oh, we manage to get on.

I have a studio of my own, so all my things are out from underfoot, which is very fortunate.

- You know, talking to Mr. and Mrs. Hopper brings a whole era to warm and affectionate remembrance, and names such as Guy Pene du Bois and the Bellows, and Reginald March, Reggie Marsh, as you call him, and many others come to mind.

And I think also there's another person from an era that perhaps one wouldn't associate with you that comes to mind too, that is Yvette Guilbert.

She was a friend of yours, wasn't she?

- Well, I hesitate to say, to take such big terms.

I saw something of her, she was very good to me.

She seemed to take a lot of interest.

It was a thing like Henri, again.

She was always, the attitude was at the giving.

- She was functioning when you were in Paris, wasn't she, Mr. Hopper?

Yvette Guilbert.

Did you go see her?

- No, I never saw her in Paris, no.

- Never saw- - I heard about her.

- What did you hear about her?

- Well, I'd rather not say what I heard about her.

- Oh, now Edward.

Well he saw at a time much to young, too long ago, and he was too young, I suppose.

But when I met her she was doing, the last time she was in America, she was doing the Jeanne Dore, medieval things.

- Well- - The "Death of Christ", and "The Birth of Christ."

And it was on that program that she asked me to be the little Madonna of the Annunciation.

Of course her interpretation, what she did with that, I hadn't heard of anyone else doing it.

The Virgin walks in the garden, and meets the angel, Gabriel.

And Gabriel tells her not only of the birth of the child, but of the life and the final.

Gabriel throws his arms out that way, and the Crucifixion is prophesied.

- I know, it was a very moving thing then, yes indeed.

- Yes, yes, and of course, Mary just flops to that.

- Wonderful.

- And it was- - Well time is hard in our heels, Mrs. Hopper.

Time is hard in our heels.

And just before we finish, perhaps you could each tell me in one sentence, do you think that, are you satisfied with the position of art as it stands at the moment?

Yes or no?

- With- - With art, modern art at the moment.

- Oh, it's as though we are going through a depression.

- (laughing) What about you, Mr. Hopper?

- I feel not at all satisfied, but it will reassert itself, the fundamentals.

- Thank you very much.

- The fundamentals will reassert themselves.

- Thank you, well you've been listening to two of the foremost citizens in what we might describe as the world of art in America.

Mr. And Mrs. Edward Hopper, thank you very much.

(bright dramatic music) - [Announcer] This is NET, National Educational Television.