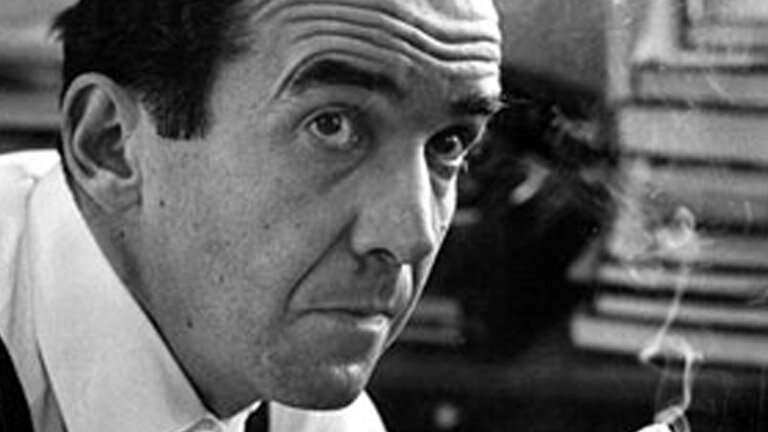

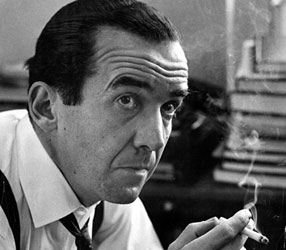

“This . . . is London.” With those trademark words, crackling over the airwaves from a city in the midst of blitzkrieg, Edward R. Murrow began a journalistic career that has had no equal. From the opening days of World War II through his death in 1965, Murrow had an unparalleled influence on broadcast journalism. His voice was universally recognized, and a generation of radio and television newsmen emulated his style. Murrow’s pioneering television documentaries have more than once been credited with changing history, and to this day his name is synonymous with courage and perseverance in the search for truth.

“This . . . is London.” With those trademark words, crackling over the airwaves from a city in the midst of blitzkrieg, Edward R. Murrow began a journalistic career that has had no equal. From the opening days of World War II through his death in 1965, Murrow had an unparalleled influence on broadcast journalism. His voice was universally recognized, and a generation of radio and television newsmen emulated his style. Murrow’s pioneering television documentaries have more than once been credited with changing history, and to this day his name is synonymous with courage and perseverance in the search for truth.

In 1937, Edward R. Murrow was sent by CBS to set up a network of correspondents to report on the gathering storm in Europe. He assembled a group of young reporters whose names soon became household words in wartime America, among whom were William Shirer, Charles Collingwood, Bill Shael, and Howard K. Smith. The group, which came to be known collectively as “Murrow’s Boys,” reported the whole of World War II from the front lines with a courage and loyalty inspired by Murrow’s own fearlessness. During the war Murrow flew in more than twenty bombing missions over Berlin, and along with Bill Shadel was the first Allied correspondent to report the horrors from the Nazi death camps.

Returning to America after the war, Murrow was surprised to find that his overseas reports had made him a star at home. With the advent of television, Murrow was approached to host a weekly program. Along with his associate, Fred Friendly, Murrow had been producing a popular radio show, Hear It Now. The television show was to be called See It Now. Joe Wershba, a reporter who worked closely with Murrow, remembers, “Neither of them knew anything about film making or television. All they knew was they wanted to do stories. Important stories.” Television was in its infancy and Murrow and Friendly had to learn the process of filmmaking and the primitive television equipment on the job.

Murrow’s love of common America led him to seek out stories of ordinary people. He presented their stories in such a way that they often became powerful commentaries on political or social issues. See It Now consistently broke new ground in the burgeoning field of television journalism. In 1953, Murrow made the decision to investigate the case of Milo Radulovich. Radulovich had been discharged from the Air Force on the grounds that his mother and sister were communist sympathizers. The program outlined the elements of the case, casting doubt on the Air Force’s decision, and within a short while, Milo Radulovich had been reinstated. This one edition of See It Now marked a change in the face of American journalism and a new age in American politics.

Soon after the Milo Radulovich program aired, it was learned that Senator Joseph McCarthy was preparing an attack on Murrow. As it happened, Murrow himself had been collecting material about McCarthy and his Senate Investigating Committee for several years, and he began assembling the program. Broadcast on March 9, 1954, the program, composed almost entirely of McCarthy’s own words and pictures, was a damning portrait of a fanatic. McCarthy demanded a chance to respond, but his rebuttal, in which he referred to Murrow as “the leader of the jackal pack,” only sealed his fate. The combination of the program’s timing and its persuasive power broke the Senator’s hold over the nation. The entire fiasco, however, caused a rift with CBS, and they decided to discontinue See It Now.

By 1961 tensions had become irreparable between Murrow and CBS and he accepted an appointment from President Kennedy as the head of the United States Information Agency. He was only to have the job for three years before being diagnosed with lung cancer. In 1964 Murrow was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 1965 died on his farm in New York. Perhaps more than any reporter before or since, Murrow captured the trust and belief of a nation and returned that trust with honesty and courage. His belief in journalism as an active part of the political process and a necessary tool within democracy has forever altered the politics and everyday life of the American people.