By: Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen

February, 2010

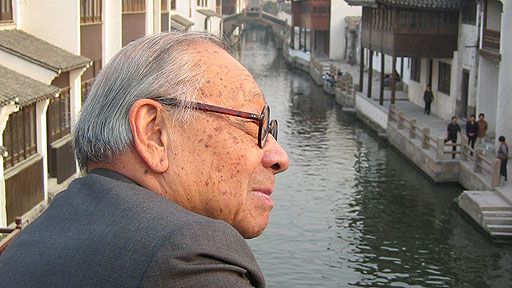

Saarinen was born in 1910 to a prominent artistic family in Helsinki, Finland. His father was a famous national romantic style architect, Eliel Saarinen, and his mother a renowned textile designer Loja Saarinen. Eero spent his childhood in Hvitträsk, a picturesque castle-like forest-home and atelier 20 miles west of Helsinki designed by his father and frequented by the likes of Jean Sibelius and Maxim Gorki. In this fairy-tale-like environment, the young Saarinen was tutored by private governesses and spent his spare time drawing in his father’s atelier. His childhood was privileged and sheltered from the social and political turmoil, which took hold of the capital before and during the First World War.

The Saarinen family emigrated into the U.S. in 1923, a year after Eliel won the second prize in the Chicago Tribune competition. The family settled on an estate called Cranbrook in Bloomfield Hills outside Detroit, where the father had been commissioned to design a private school and an art academy. Much like Hvittrask, it was a picturesque quasi-medieval community seemingly untouched by world events, like those unfolding in nearby Detroit during recession

Yale, where Saarinen studied at the School of Fine Arts from 1931 to 1934 was an equally closed enclave featuring boys from privileged backgrounds roaming around the picturesque campus. The university was in the middle of building its residential colleges in collegiate Gothic, a nod to tradition over change. All it took was a letter from his father Eliel stating that “My boy would love to study at Yale” to Dean Everett Victor Meeks to gain acceptance.

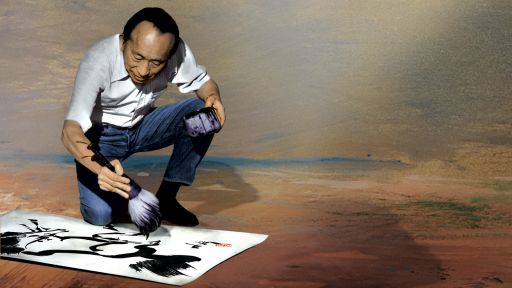

Saarinen’s artistic talent – and there is no question that he was exceptionally gifted – made itself apparent much earlier than with ordinary mortals. He executed his first designs at the Cranbrook campus – cast-iron gates, gargoyles, dining room furniture, and a bedroom vanity – starting at bare age of fifteen. He was at that time already an accomplished artist working in various mediums – ceramics, printing, metalwork. Much has been made of the fact that Saarinen was an artist at heart and that he studied sculpture in Paris for a year before enrolling at Yale to study architecture

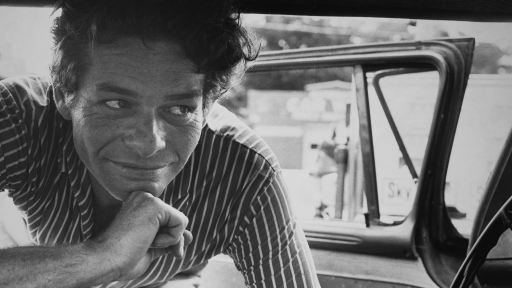

Saarinen’s entrance to the world of architecture cannot be discussed solely in the content of his biography and individual talent. Here I would like to recall George Kubler who talks about how “each man’s lifework is work in a series extending beyond him in either or both directions…” Saarinen entered what Kubler called a “track” at the tail end of the Beaux-Arts tradition, which formed the basis of his architectural training, and at the moment when the influence of European modernism started to be felt in American architecture. As a consequence, Saarinen student work done during a three-year period, which won him many national prizes, fluctuated between two opposing traditions: classicism and modernism, which are based on two different time concepts. The classical tradition emphasizes the timeless principles and values, while the modern tradition insists that architecture should reflect its own time, both through programmatic focus as well as through style.

Saarinen traveled to Europe for the first time in 1934 under the auspices of the Matchum scholarship, and his design for the Swedish Theatre during a brief stint working at an architectural office in Helsinki gives a sense of where he stood architecturally at the end of his training. He was clearly drawn to the white walls and pure geometric shapes of modern classicism and its emphasis of the timeless essence of architecture during the troubled times.

Upon his return from Europe back to the U.S. in 1936, Saarinen started to experiment with several versions of modern architecture, each of which embodied a different idea about architecture’s relationship to time and change during the period of economic hardship and social unrest.

Working with his father Eliel, Saarinen can be given credit for introducing modern architecture to American mainstream culture. Their winning entry for the Smithsonian Museum of Art competition in 1939 almost resulted in the first-ever government-sponsored modernist building. The father-son team also deserves credit for designing the first modernist school in the U.S., the Crow Island School, in Wichiga, Illinois, which encompassed both indoor and outdoor classrooms, and the first modernist church, the First Christian Church in Columbus Indiana.

Saarinen’s thinking about modern design and its relationship to time changed radically after he met Charles Eames, who studied at the newly founded Cranbrook Art Academy under Eliel during the late 1930s. Their 1940 winning entry to the Museum of Modern Arts competition “Organic Design in Home Furnishing” took the idea of temporariness even further by emphasizing material and structural experimentation. Their Conversation Chair combined a seat, an armrests and a backrest into one form by bending plywood in two directions. This too had a strange alignment with time; since the technology had not yet been invented to achieve this goal the plywood seat had to be upholstered due to splintering. Their design was, in other words, ahead of its time.

Saarinen’s dual vision about modern architecture’s relationship to time – one emphasizing permanence and order the other change and process – carried on to a series of domestic projects during late 1930s and early 1940s. The Wermuth House in Forth Wayne Indiana sits confidently on a sloped site to benefit from sun and views. The house is one-of- a-kind and allows its inhabitants to live their lives according to nature’s soothing rhythms and patterns. In contrast, the Demountable Space and the Unfolding House, both from the early 1940s, follow a different idea of time, namely that dictated by industrial processes. Each of them could be transported on a truck and speedily mounted on various sites in large numbers.

So when Saarinen came to his own in 1950 after his father’s death, he understood that time was not a given, but could be manipulated, stretched, imagined, and suspended. The look Saarinen helped to create lives on in what we today call mid-century design and in popular culture.

Saarinen once remarked to his second wife Aline – a celebrated author and journalist – that she lived in “rabbit time,” while architects lived in “elephant time.” Although his own lifespan was hardly elephantine, Saarinen seem to have believed that at least his buildings should have an elephant’s mind: they should recall the past, engage the present, and speculate about what the future might bring.

Major funding for American Masters — Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Saw the Future is provided by the A. Alfred Taubman Foundation. Additional funding is provided in part by American Institute of Architects, National Endowment for the Arts, The Durst Family, Vital Projects Fund, Eric and Katherine Larson Family Fund, MCR Development LLC, Gerald D. Hines, Elise Jaffe + Jeffrey Brown, KieranTimberlake, KPF Foundation, and Daryl and Steven Roth Foundation.

Major support for American Masters is provided by AARP. Additional funding is provided by Rosalind P. Walter, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, Judith and Burton Resnick, Ellen and James S. Marcus, Lillian Goldman Programming Endowment, The Blanche & Irving Laurie Foundation, Vital Projects Fund, Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, The André and Elizabeth Kertész Foundation, Lenore Hecht Foundation, Michael & Helen Schaffer Foundation, and public television viewers.