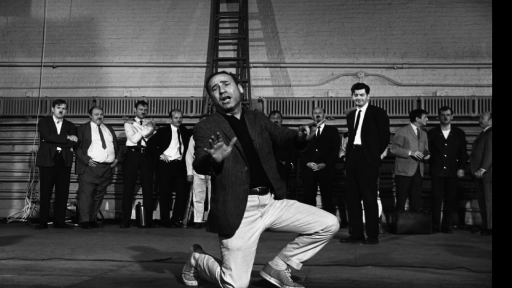

Filmmaker Robert Trachtenberg takes us behind the curtain on how he directed the film, American Masters – Gene Kelly: Anatomy of a Dancer.

Filmmaker Robert Trachtenberg takes us behind the curtain on how he directed the film, American Masters – Gene Kelly: Anatomy of a Dancer.

Q: What made you interested in doing a film on Gene Kelly?

A: My other career is as a photographer, and I pitched a Gene Kelly story to the NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE in 1994. It was a fashion story — an homage to Kelly’s style, which is so iconic and American. We cast a model to play Gene and had backdrops and sets built that replicated some of his most famous movies. The Times suggested we interview Gene. He agreed, and I shot his portrait for the story. After his death I realized there hadn’t been a full-length documentary on him, and so it began.

Q: How did the original photo shoot go?

A: It went off without a hitch. We shot at his house. It was two years before his death and he was a little frail — he was having hip and back problems and I remember him telling me that the ligaments in his legs were shot from all those years of dancing. We got along pretty well — old and ill he was still very cool. Since that was the time “That’s Entertainment! III” was being released, he requested me for a few other magazine shoots over the next few months.

Q: Did you “talk shop” with him?

A: I tried to be cool, but since I was also recreating some of his classic images for the NEW YORK TIMES, it was a great excuse to ask about specific scenes and how they were done.

Q: And?

A: Well, he told me he bought the roller skates for the “I Like Myself” number from “IT’S ALWAYS FAIR WEATHER” down the block from his house at Pioneer Hardware on Beverly Drive. He also mentioned that the skates were not altered in any way — they weren’t locked to his shoes, so when he tapped in them, he had no help.

Q: What were some of the things that surprised you as you began the film?

A: Well, frankly, everyone I contacted telling me how difficult he could be professionally. But I really got to the root of that when I spoke to Nina Foch, who co-starred in “AN AMERICAN IN PARIS.” She was saying what a pain he was and I said, “Are you telling me he was difficult because he wanted his dressing room painted a certain shade of blue, or because he wanted to get the scene right?” “He wanted to get it right,” she replied. So after that, I realized that the temperament came out of the perfectionism and not just random movie star behavior.

Q: Was his family guarded about his life?

A: Actually, they were wonderful. His first wife Betsy Blair is in the process of writing her memoirs, so everything was very fresh for her. And Gene’s eldest daughter Kerry has a really terrific perspective on him and was very frank and honest. There is a rift between Gene’s family and Patricia Ward Kelly, his last wife that was not relevant to the film. She chose not to participate, and Betsy and the children will not discuss her.

Q: Did you feel you had to address the comparisons between Gene and Fred Astaire?

A: Yes, because EVERYONE raised the issue and I finally came to the conclusion that it was brought up so much because these two guys [were] dancing at this level alone — there was no one else in the pool with them. Some people literally said they were “in the Astaire camp” or “the Kelly camp” — they couldn’t cross party lines! And when you see the film, we show how different they truly were.

Q: What proved difficult while making the film?

A: The simple fact that his career went into such a slide after “SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN” he really didn’t have a bona-fide commercial or critical hit after that. So we had forty years of disappointments and let downs to deal with. Some of the films were noble failures — particularly INVITATION TO THE DANCE. I don’t think it’s something that holds up as a whole, but a few of the individual sections are really quite nice. People really are critical and dismissive of his later years, and it is true that he was not a very good director on his own, but his intentions were good and he was trying, really trying, to get his vision across, to either publicize dance and particularly dance in America or try new directing comedies or westerns.

Q: Why wasn’t Stanley Donen interviewed for the film?

A: Essentially he relayed a message saying he had nothing nice to say, so he’d rather not say anything at all. It’s sad that the relationship is still so toxic for him after all of these years. We use an archival interview with him so that he does have a voice in the film.

Q: So what do you think Kelly’s appeal was?

A: You know right before I started the film, this very young woman was in my office repairing my computer and my assistant turned to her and said, “What happens when I say Gene Kelly to you?” and she instantly said, “I smile.” The guy was a movie star in the classic sense of the word — he had that X quality that you cannot define. But he actually had the talent to back up the sheer charisma. He was very frank in some of his archival interviews, he knew that some of his films were dated, that numbers didn’t work, but his appeal really transcends and even filters down to the movie audience of today. When I was around him, he was still getting fan mail from thirteen-year old girls!

Q: How does the dance community think of him?

A: It depends on who you’re talking to and how well versed they are in stage dance as well as film dance. He replaced the original choreography in many of his films — he replaced Balanchine’s work in SLAUGHTER ON TENTH AVENUE and Agnes de Mille’s in BRIGADOON. But in Balanchine’s case, the censor’s would have never let the original scenario onto the screen, so Kelly had to change it. In “Brigadoon” he needed a hit, and he was a choreographer in his own right, so it’s understandable. His choreography is highly respected by dance critics and fellow dancers who know their history.

Q: How is this film different from other profiles of Kelly?

A: First of all, we acknowledge the failures as well as the successes. Additionally, we discuss his professional “marriage” to Stanley Donen in more depth than anyone has previously done. And the personal life — the competitive nature he brought to weekends at home, his politics and the blacklist period are also delved into. I suppose with the passing of time, the people I interviewed seemed willing to be more candid.

Q: What kept you interested in Kelly throughout the process?

A: I didn’t realize it until about halfway in, but it was a very similar situation to George Cukor, who I made a film on last year for AMERICAN MASTERS. I’m not as interested in personalties with alcohol and drug problems — I don’t find it glamorous or tragically romantic like some people do. I’m more drawn to someone who can get up and go to work decade after decade, plugging away at trying to do something fresh and new. When you really look at it, he was starring, singing, dancing, acting, choreographing and directing his own numbers — there is no precedent for this career.

Q: Any last thoughts?

A: Just that the idea of what he was trying to do — present dance to as wide an audience as possible, to point out that dance is a form of athletics as well as art, to keep trying to film dance in new ways — these are very basic ideas, but sometimes the simplest ideas are the best…