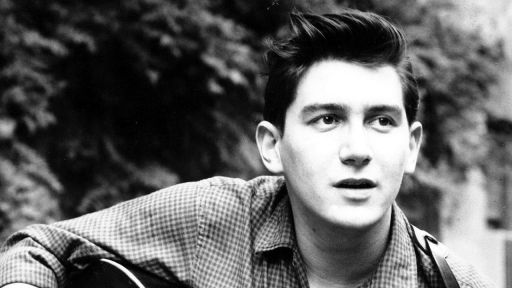

Hank Williams in 1948. Photo: MGM Records

More than fifty years after his death, Hank Williams ranks among the most powerfully iconic figures in American music.

Iconic to the point that man and myth are inextricably entwined. He set the agenda for contemporary country songcraft and sang his songs with such believability that we feel privy to his world, despite the fact that he left no in-depth interviews and just a few letters. His brief life and tragic death have only compounded his appeal.

Hank William’s early life

Born in the tiny settlement of Mount Olive in south-central Alabama on September 17, 1923, Hiram “Hank” Williams grew up with a sense of apartness that never left him. A spinal condition, in all likelihood spina bifida occulta, ensured that he couldn’t work in the same occupations as his contemporaries: logging or farming. When Hank was six years old, his aloneness was compounded when his father, Lon, went into a veterans’ hospital; Hank would see him just twice in the next seven years. His mother, Lilly, ran rooming houses, first in Greenville, Alabama, and then in Montgomery.

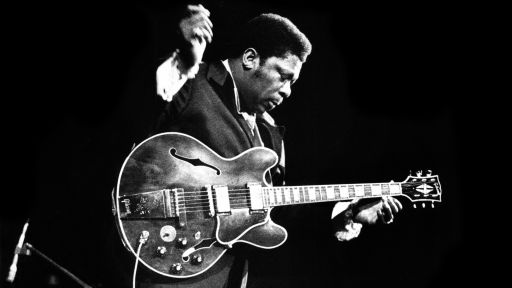

Local influences shaped Hank’s music more profoundly than the big stars of the day. The gospel songs of both the black and white communities taught him that music, whether sacred or secular, must have a spiritual component. He learned traditional folk ballads and early country songs from neighbors and friends, and blues from a local African-American street musician, Rufus Payne (also known as Teetot). Payne not only taught Hank how to play the guitar, but helped him overcome his innate shyness. The blues feel that suffuses much of Hank Williams’ work is almost certainly Teetot’s legacy.

Entering local talent talent contests soon after moving to Montgomery in 1937, Hank had served a ten-year apprenticeship by the time he scored his first hit, “Move It on Over,” in 1947. He was twenty-three then, and twenty-five when the success of “Lovesick Blues” (a minstrel era song he did not write) earned him an invitation to join the preeminent radio barndance, Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. His star rose rapidly. He wrote songs compulsively, and his producer/music publisher, Fred Rose, helped him isolate and refine those that held promise. The result was an unbroken string of hits that included “Honky Tonkin’,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “Mansion on the Hill,” “Cold, Cold Heart,” “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in Love with You),” “Honky Tonk Blues,” “Jambalaya,” “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” and “You Win Again.” He was a recording artist for six years, and, during that time, recorded just 66 songs under his own name (together with a few more as part of a husband-and-wife act, Hank & Audrey, and a more still under his moralistic alter ego, Luke the Drifter). Of the 66 songs recorded under his own name, an astonishing 37 were hits. More than once, he cut three songs that became standards in one afternoon.

“Luke the Drifter”

The fourteen “Luke the Drifter” recordings were narrations and talking blues. Luke the Drifter walked with Hank Williams and talked through him. If Hank Williams could be headstrong and willful, a backslider and a reprobate, then Luke the Drifter was compassionate and moralistic, capable of dispensing all the sage advice that Hank Williams ignored. Luke the Drifter had seen it all, yet could still be moved to tears by a chance encounter on his travels. Although little known in comparison with the hits, the “Luke the Drifter” narrations were the closest Hank Williams came to bearing his soul.

As a songwriter, Hank Williams matured surprisingly quickly, and his fractious relationship with his first wife, Audrey (whom he’d married in 1943), provided him with much of the raw material. After Tony Bennett covered “Cold, Cold Heart” in 1951, his songs found a broader market, a market that Hank himself would have found it hard to penetrate. To the end, he was unapologetically Southern, unable to make the compromises that Elvis Presley would make just a few years later. But Williams’ songs went where he couldn’t, and from 1951 onward, there was a rush to reinterpret them for the pop market. Ironically, those pop versions, which comfortably outsold Williams’ originals in the early Fifties, now sound over-ornamented and outdated, while Williams’ spare and haunting versions sound ageless.

Hank William’s later life

It all fell apart remarkably quickly. Hank Williams grew disillusioned with success, and the unending travel compounded his back problem. A spinal operation in December 1951 only worsened the condition. Career pressures and almost ceaseless pain led to recurrent bouts of alcoholism. He missed an increasing number of showdates, frustrating those who attempted to manage or help him. His wife, Audrey, ordered him out of their house in January 1952, and he was dismissed from the Grand Ole Opry in August that year for failing to appear on Opry-sponsored showdates. Returning to Shreveport, Louisiana, where he’d been an up-and-coming star in 1948, he took a second wife, Billie Jean Jones, and hired a bogus doctor who compounded his already serious physical problems with potentially lethal drugs.

In late December 1952, Hank Williams returned to Montgomery, attempting to recuperate, but decided to meet two prearranged showdates on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. He died en route, aged just twenty-nine. Contrary to myth, Williams did not die with his star in the ascendant. “Jambalaya” had been one of the best-selling records of 1952, but while his records were topping the charts, he was so unreliable that he was reduced to playing beerhalls in Texas and Louisiana. There’s a persistent myth that he would have returned to the Opry had he not died on New Year’s Day 1953, but surviving correspondence suggests nothing more than a few more beerhall gigs. On a record released after his death, Williams sang of being pursued by the “Pale Horse and His Rider.” On a home recording made shortly before his death, he directly addressed “The Angel of Death.” It’s impossible to escape the feeling that he lived with the spirits every day, and drank in part to escape them.

Timing is everything and Hank Williams came and went at precisely the right time. Country music was a cottage industry at the time of his arrival, yet, just a few years after his death, it was shaking off its “hillbilly” image. An artist as unapologetically rural as Hank Williams would have been shown the door. Elvis Presley appeared on the Grand Ole Opry just two years after Hank was dismissed, and Nashville’s response to Elvis was to nurture artists who could cross between country and pop, leading to the birth of the Nashville Sound. Hank Williams didn’t belong in the Nashville Sound era, but his tragically early death spared him the indignity of trying. Instead, his songs have lived on, reintrepreted by artists as diverse as Bob Dylan, jazz diva Norah Jones, crooner Perry Como, R&B star Dinah Washington, and British punk band, The The.

By: Colin Escott