Introduction from Salinger. Simon & Schuster. 2013. 720 pages.

Introduction from Salinger. Simon & Schuster. 2013. 720 pages.

By David Shields and Shane Salerno

J. D. Salinger spent ten years writing The Catcher in the Rye and the rest of his life regretting it.

Before the book was published, he was a World War II veteran with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; after the war, he was perpetually in search of a spiritual cure for his damaged psyche. In the wake of the enormous success of the novel about the “prep school boy,” a myth emerged: Salinger, like Holden, was too sensitive to be touched, too good for this world. He would spend the rest of his life trying and failing to reconcile these completely contradictory versions of himself: the myth and the reality.

The Catcher in the Rye has sold more than 65 million copies and continues to sell more than half a million copies a year; a defining book for several generations, it remains a totem of American adolescence. Salinger’s slim oeuvre—four brief books—has a cultural weight and penetration nearly unmatched in modern literature. The critical and popular game over the past half-century has been to read the man through his works because the man would not speak. Salinger’s success in epic self-creation, his obsession with privacy, and his meticulously maintained vault—containing a large cache of writing that he refused to publish— combined to form an impermeable legend.

Salinger was an extraordinarily complex, deeply contradictory human being. He was not—as we’ve been told—a recluse for the final fifty-five years of his life; he traveled extensively, had many affairs and lifelong friendships, consumed copious amounts of popular culture, and often embodied many of the things he criticized in his fiction. Far from being a recluse, he was constantly in conversation with the world in order to reinforce its notion of his reclusion. What he wanted was privacy, but the literary silence that reclusion brought became as closely associated with him as The Catcher in the Rye. Much has been made of how difficult it must have been for Salinger to live and work under the umbrella of the myth, which is undeniably true; we show the degree to which he was also invested in perpetuating it.

Other books about Salinger tend to fall into one of three categories: academic exegeses; necessarily highly subjective memoirs; and either overly reverential or overly resentful biographies that, thwarted by lack of access to the principals, settle for perpetuating the agreed-upon narrative. Previous biographies have tended to rely on the relatively small collections of Salinger papers and unpublished manuscripts found at Princeton University and the University of Texas, Austin. The result is the recycling of the same information from a very shallow well and the republication of inaccurate information. The letters we excerpt, ranging from 1940–2008, are from Salinger to his closest friends, lovers over many decades, World War II brothers-in-arms, spiritual teachers and others; the overwhelming majority of the letters have never been seen before.

We began with three goals: we wanted to know why Salinger stopped publishing; why he disappeared; and what he had been writing the last forty-five years of his life. Over nine years and across five continents, we interviewed more than two hundred people, many of whom had previously refused to go on the record and all of whom spoke to us without preconditions. We aim to provide a multilayered perspective on Salinger, offering first-person accounts from Salinger’s fellow World War II counterintelligence agents with whom he maintained lifelong bonds, lovers, friends, caretakers, classmates, editors, publishers, New Yorker colleagues, admirers, detractors, and many prominent figures who discuss his influence on their lives, their work, and the broader culture.

By reproducing material that has never been published before—more than one hundred photographs and excerpts from journals, diaries, letters, memoirs, court transcripts, depositions, and recently declassified military records—we hope to deliver many factual clarifications and significant revelations. We particularly illuminate the last fifty-five years of his life: a period that, until now, had remained largely dark to biographers.

Still, we faced two major obstacles: The first was that key people had died before we began this project, and the second was that while certain members of the Salinger family initially cooperated, the Salinger family ultimately did not participate in formal interviews. Although they didn’t speak directly to us, they had spoken, and through a careful dissection of their public statements and our obtaining of private letters and never-before-published documents, their voices appear throughout this book. In addition, many people unwilling to talk on the record directed us to crucial information and passed on photographs, letters, and diaries they had kept secret their entire lives; half a dozen of our most important interviewees spoke to us only after Salinger’s death.

We also provide twelve “conversations with Salinger”: revealing encounters over half a century between journalists, photographers, seekers, fans, family members, and the man who never stopped living his life like a counterintelligence agent. These episodes place the reader on increasingly intimate terms with an author who had been adamantly inaccessible for more than half a century.

—

There were two emphatic demarcation points in Salinger’s life: World War II and his immersion in the Vedanta religion. World War II destroyed the man but made him a great artist. Religion provided the comfort he needed as a man but killed his art.

This is the story of a soldier and writer who escaped death during World War II but never wholly embraced survival, a half-Jew from Park Avenue who discovered at war’s end what it meant to be Jewish. This is an investigation into the process by which a broken soldier and a wounded soul transformed himself, through his art, into an icon of the twentieth century and then, through his religion, destroyed that art.

Salinger was born with an embarrassing congenital deformity that shadowed his entire life. A college dropout, mercurial talent, wise-guy dandy out of an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, he was ferociously determined to become a great writer. He dated Oona O’Neill—the gorgeous daughter of arguably America’s greatest playwright, Eugene O’Neill—and published short stories in the Saturday Evening Post and other “slicks.” After the war, Salinger refused to allow any of these stories to be republished. The war had killed that author.

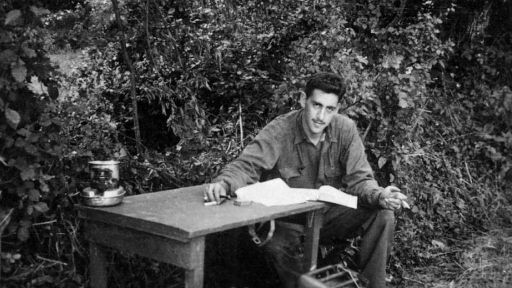

A staff sergeant in the 12th Infantry, Salinger served through five bloody campaigns of the European Theater of 1944–45. His job, as a counterintelligence agent, involved interrogating prisoners of war; working the shadow war, the no-man’s-land between Allies and Germans; gathering information from civilians, the wounded, traitors, and black marketers. He saw firsthand the war’s destruction and devastation. When the end was near, he and other soldiers entered Kaufering IV, an auxiliary of the Dachau concentration camp. Soon after witnessing Kaufering, Salinger checked himself into a Nuremberg civilian hospital, a psychic casualty of the war’s final revelation.

Throughout the war and during his postwar hospitalization, Salinger had carried a personal talisman for survival inside the war’s corpse machine: the first six chapters of a novel about Holden Caulfield. Those chapters would become The Catcher in the Rye, which redefined postwar America and can best be understood as a disguised war novel. Salinger emerged from the war incapable of believing in the heroic, noble ideals we like to think our cultural institutions uphold. Instead of producing a combat novel, as Norman Mailer, James Jones, and Joseph Heller did, Salinger took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel. So, too, in Nine Stories, the ghost in the machine is postwar trauma: a suicide begins the book, is barely averted in the middle of the book, and ends the book.

Profoundly damaged (not only by the war), he became numb; numb, he yearned to see and feel the unity of all things but settled for detachment toward everyone’s pain except his own, which first overwhelmed and then overtook him. During his second marriage, he steadily distanced himself from his family, spending weeks at a time in his detached bunker, telling his wife, Claire, and children, Matthew and Margaret, “Do not disturb me unless the house is burning down.” Toward Margaret, who dared to embody the rebellious traits his fiction canonizes, he was startlingly remote. His characters Franny, Zooey, and Seymour Glass, despite or because of their many suicidal madnesses, had immeasurably more claim on his heart than his flesh and-blood family.

A drowning man, grasping desperately for life rafts, drifting farther away from the taint of the everyday, occupying increasingly abstract realms, he disappeared into the solace of Vedantic philosophy: you are not your body, you are not your mind, renounce name and fame. “Detachment, buddy, and only detachment,” he wrote in Zooey. “Desirelessness. ‘Cessation from all hankerings.’ ” His work tracks exactly along this physical metaphysical axis; book by book, he came to see his task as the dissemination of doctrine.

Salinger’s vault, which we open in the final chapter, contains character and career-defining revelations, but there is no “ultimate secret” whose unveiling explains the man. Instead, his life contained a series of interlocking events—ranging from anatomy to romance to war to fame to religion— that we disclose, track, and connect.

Creating a private world in which he could control everything, Salinger wrenched immaculate, immortal art from the anguish of World War II. And then, when he couldn’t control everything—when the accumulation of all the suffering was too much for a human as delicately constructed as he to withstand—he gave himself over wholly to Vedanta, turning the last half of his life into a dance with ghosts. He had nothing anymore to say to anyone else.

—

Introduction from Salinger. Simon & Schuster. 2013

Salinger airs nationally on American Masters Tuesday, January 21, 2014 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings).