Playing fast and loose with the Six Degrees of Separation game, American Masters looks into its archives to see what the great American writer J.D. Salinger has in common with the lives and careers of 11 other American Masters.

Judy Garland, circa 1940s.

Salinger was a fan of Judy Garland

J.D. Salinger (1919 – 2010) was a contemporary of Judy Garland (1922 – 1969), the great entertainer whose singing and acting spanned radio, blockbuster films and cabaret.

“He talked a lot about Judy Garland and child actors, the innocence of actors and the beauty of their purity. He liked the innocence of childhood before pretension set in: the clear, simple way she sang in the Wizard of Oz.” — Jean Miller, Salinger’s longtime friend and romantic interest (source: Salinger, by David Shields and Shane Salerno).

Billie Jean King reacts during a match against Betty Ann Gruob Stuart, Jan. 8, 1974. AP Photo/SJV.

Salinger could have had a friendly volley with Billie Jean King

In the summer of 1930, city boy Jerome was sent to the affluent Camp Wigwam in Harrison, Maine, where according to John Skowe, a former staff writer at Time, the 11-year-old “played a fair game of tennis.” On the opposite side of the country and many years later, tennis legend Billie Jean King (b. 1943) learned her moves at the age of 12, on the public courts of Long Beach, California.

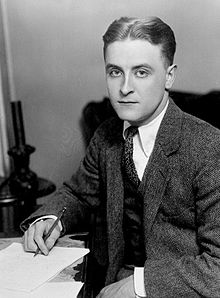

F. Scott Fitzgerald in "The World's Work" (June 1921 issue).

Salinger followed in the footsteps of F. Scott Fitzgerald

While in his early 20s, J.D. Salinger hired the same literary agency that had represented F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940): Harold Ober. The agent Dorothy Olding would represent Salinger for 50 years. Both Fitzgerald and Salinger won instant fame with their debut novels, Fitzgerald with This Side of Paradise (1920), and Salinger with The Catcher in the Rye (1951).

Algonquin Round Table attendees Art Samuels, Charlie MacArthur, Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott, circa 1919, the year J.D. Salinger was born.

Salinger would not have sat at the Algonquin Round Table

Unlike the literati and entertainers that famously dined and drank together at the Algonquin Hotel in the 1920s, J.D. Salinger’s life post-Catcher in the Rye suggests he preferred more discreet companions. Salinger did not share the press-friendly attitude of the garrulous members of the Algonquin Round Table, even if it did include Harold Ross, founder of Salinger’s favorite magazine, The New Yorker. But Salinger was no stranger to the Algonquin itself. In the early 1970s, he took his love interest, the young writer Joyce Maynard, to the Algonquin to meet his friends William Shawn, Salinger’s editor at The New Yorker, and journalist Lillian Ross.

The hearts of Salinger and Eugene O’Neill were broken by the same woman (who ran off with another American Master, Charlie Chaplain)

Left to right: American Master Eugene O'Neill; American Master J.D. Salinger; Oona O'Neill; American Master Charlie Chaplin

Native New Yorkers J.D. Salinger and playwright Eugene O’Neill (1888 – 1953) had their hearts broken by the same young woman: Oona O’Neill, J.D.’s pre-war love interest and Eugene’s daughter, a fetching debutante. Oona married the much-older legend of silent film, Charlie Chaplin (1889 – 1977), and neither her disapproving father or Salinger ever spoke to her again.

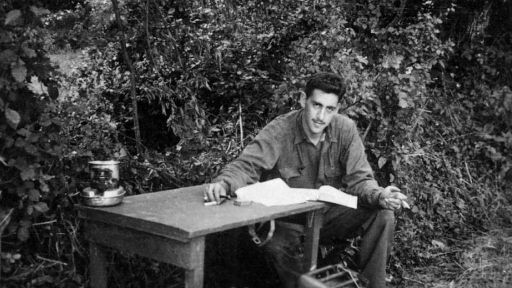

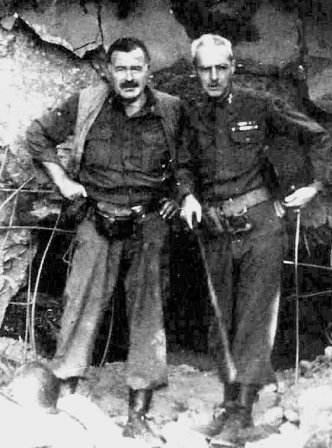

Ernest Hemingway (left) with Col. Charles Lanham in Hürtgen Forest, Germany, 1944. Salinger’s 4th Division fought there.

World Wars deeply wounded Salinger and Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961) and J.D. Salinger were both deeply wounded by World Wars — Hemingway physically in the first, and Salinger psychologically in the second. While serving in World War II, Salinger met Hemingway, who gave the young writer encouraging feedback on The Catcher in the Rye. According to American Masters Ernest Hemingway director DeWitt Sage, World War I was a large influence on how Hemingway lived his life and wrote.

“But on pain and on childhood, and early experience, the most dramatic thing that happened to Hemingway was that he was severely wounded in World War I. And I agree with what Ann Douglas, a professor at Columbia, says in the film, that he got away with his life and he also got away with material he would use for the rest of his life. I think this is true, but I don’t think it was an affirmative experience. I just think he was a born writer who somehow sensed that he had great material here to work with. Many great writers are the same. His grave wound gave him material and sensitized him, but he was already going to be a writer.” — DeWitt Sage

David Shields, co-author of Salinger, sees World War II as a “covert meditation” in Salinger’s literary works. Though Salinger published stories about soldiers and veterans, unlike in the foreign settings and aggressive situations of Hemingway’s works, Salinger’s characters are confronted with domestic and ordinary circumstances, often paired with innocents. In a film outtake from Salinger, Bookworm radio host Michael Silverblatt points out that Salinger’s strength was his characters’ poignant, sincere dialogues, yet he was writing in a time dominated by Hemingway, whose style was to leave most important things left unsaid.

Watch Salinger Film Outtake with Bookworm Host Michael Silverblatt Comparing Salinger and Hemingway

Salinger and Sam Goldwyn had different takes on “Uncle Wiggily Goes to Connecticut”

Salinger and Sam Goldwyn had different takes on “Uncle Wiggily Goes to Connecticut”

The Polish-born American movie industry mogul Sam Goldwyn (1882 – 1974) bought the film rights for Salinger’s story “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,” a critique of the shallowness of American suburbia. Goldwyn assembled a creative team, and spent much of 1949 transforming it into a sentimental love story, My Foolish Heart. Though the film gave Susan Hayward an Oscar nomination for best actress, Salinger could not stand what Goldwyn did with the story and critics didn’t like it much either.

Harper Lee poses for Life magazine in 1961.

Salinger and Harper Lee left us hanging

Salinger’s and Harper Lee’s most famous protagonists were embraced by their younger readers: who didn’t feel like Holden Caulfield, and who didn’t want to be Scout or Jem Finch? And much to the dismay of their readership, both authors largely denied fans the future books they hoped to continue growing up and old with. One of the biggest best-sellers of all time, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) is the first and only novel by Harper Lee, who once said that she wanted to be South Alabama’s Jane Austen. Lee won the Pulitzer Prize and became a mystery when she stopped speaking to press in 1964. Salinger’s last published short story, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” nearly filled the June 19, 1965 edition of The New Yorker. Its hero is a seven-year-old Seymour Glass writing a letter home from summer camp.

John Lennon in New York City.

The Catcher in the Rye tragically links Salinger and John Lennon

Mark David Chapman, who shot and killed the musician and former Beatles member John Lennon (1940 – 1980) outside his New York City apartment on December 8, 1980, admitted an affinity to the character Holden Caulfield, who despised phony people.

“I’m not blaming a book. I blame myself for crawling inside of the book and I certainly want to say J.D. Salinger and The Catcher in the Rye didn’t cause me to kill John Lennon. In fact, I wrote to J. D. Salinger, I got his box number from someone, and I apologized to him for this. I feel badly about that. It’s my fault. I crawled in, found my pseudo-self within these pages…and played out the whole thing.”– Mark David Chapman

Writer and Civil Rights activist James Baldwin (left) with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Salinger and James Baldwin gave us rebellious protagonists and both have protective estates

The writers James Baldwin (1924 – 1987) and Salinger were born and raised in New York City, where Baldwin grew up poor in Harlem and Salinger rich on Park Avenue. Salinger’s debut novel in 1951 featured a rebellious prep-school student fed up with all the “phony” people. Baldwin’s autobiographical first novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain (1953) questions the constraints of the Christian Church and reveals the father he struggled against was not truly his. As they did in their lifetimes, their estates protect their writing and correspondence vigilantly, even if Salinger suffered breaches in others’ memoirs and the recent Internet posting of stories scooped from the archives of Princeton University and The University of Texas.

“The situation, for anyone still in doubt, is that if J.D. Salinger or James Baldwin writes you a letter, then you own the paper and the ink, but ownership of the contents – the intellectual property – resides with the author and then, for 70 years after the author’s death, his or her estate (minor variations apply from country to country). The judge in the Salinger case [barring Ian Hamilton’s Salinger biography] allowed practically no application of fair use to unpublished correspondence.” — James Campbell, author of a book on James Baldwin, in an article in the Guardian in 2005.

–BY CHRISTINA KNIGHT

See what other connections exist between American Masters with our Six Degrees Game. American Masters launches its 28th season with the 200th episode in its series: the exclusive director’s cut of Shane Salerno’s documentary, Salinger, airing nationally 9-11:30 p.m. on January 21, 2014.