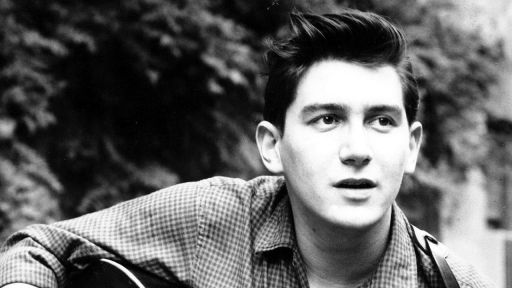

Nat King Cole crowns a very short list of the most identifiable and memorable voices in American music.

This ground breaking American icon’s impact continues to cross the world’s cultural and political boundaries. The story of his life is a study in success in the face of adversity and the triumph of talent over the ignorance of prejudice.

This ground breaking American icon’s impact continues to cross the world’s cultural and political boundaries. The story of his life is a study in success in the face of adversity and the triumph of talent over the ignorance of prejudice.

Nat King Cole’s early career and trio

Born Nathaniel Adams Coles on March 17, 1919 (although 1916 and 1917 have also been cited), in Montgomery, Alabama, Cole was born into a family with a pivotal position in the black community; his father was pastor of the First Baptist Church. In 1921, the family migrated to Chicago, part of the mass exodus seeking a better life in the prospering industrial towns of the north. At four years old, he was learning the piano by ear from his mother, a choir director in the church. At 12 years old he took lessons in classical piano, but was soon to be bitten by the Jazz bug — inescapable in Chicago. He left school at 15 to pursue a career as a jazz pianist. Cole’s first professional break came touring in the revival of the show “Shuffle Along.” When the show folded he was stranded in Los Angeles. Cole looked for club work and found it at the Century Club on Santa Monica Boulevard, where he made quite an impression with the “in” crowd.

In 1939, Cole formed a trio with Oscar Moore on guitar and Wesley Prince on bass, notably they had no drummer. Gradually Cole would emerge as a singer. The group displayed a finesse and sophistication which expressed the new aspirations of the black community. In 1943, he recorded “Straighten Up And Fly Right,” for Capitol Records, inspired by one of his father’s sermons. It was an instant hit, assuring Cole’s future as a pop sensation. With the addition of strings in 1946 “The Christmas Song” began Cole’s evolution into a sentimental singer. In the 1940s he made several memorable sides with the Trio, including “It’s Only A Paper Moon” and “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons.” But by 1948, and “Nature Boy,” the move away from small-group jazz, towards his eventual position as one of the most popular vocalists of the day, was underway.

Nat King Cole’s later career

During the 1950s, he was urged to make films, but his appearances were few and far between, including character parts in BLUE GARDENIA, CHINA GATE, and ST. LOUIS BLUES. However, Cole was not a natural actor — his enormous appeal lay in concerts and records.

During the years of Cole’s enormous popularity in the “easy listening” field he said he felt that he was “just adjusting to the market: as soon as you start to make money in the popular field, they scream about how good you were in the old days, and what a bum you are now.” At this time jazz fans had to turn out to see him in the clubs to hear his phenomenal piano — an extension of the Earl Hines style that had many features of the new, hip sounds of bebop. If Cole had not had such an effecting singing voice he might well have been one of bebop’s leaders. Bebop was an expression of black pride, but, it should be noted, so was Cole’s career, proving that whites did not possess the monopoly on sophistication.

Cole took racism on the chin, once attacked on stage in Birmingham, Alabama (after which he stuck to the promise that he would never return to the South) and refusing to move when he met objections from white neighbors having bought a house in fashionable Beverly Hills. Significantly, Cole became the first black television presenter but was forced to abandon the role in 1957, when the show could not find him a national sponsor.

Nat Cole’s “unforgettable” voice, with its honeyed velvet tones in a rich, easy drawl, is one of the great moments in music, and saw him accepted in a “white” world. With high profile friends, such as Frank Sinatra, his position entailed compromises that gained him the hostility of civil rights activists in the early 1960s. But Cole was a brave figure in a period when racial prejudice was at its most demeaning, Cole suffered the indignity of being “whited up” for some of his TV performances, to make him more “accessible” to a white audience. Before his death from lung cancer in 1965, Cole was planning a production of James Baldwin‘s play, “Amen Corner,” displaying an interest in radical black literature at odds with his image as a sugary balladeer.