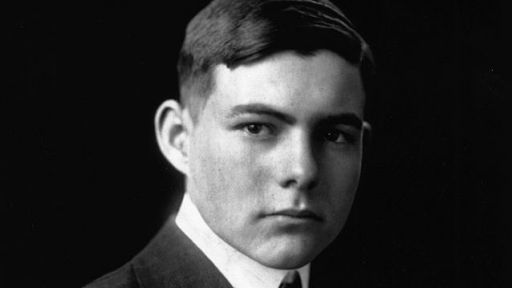

Ernest Hemingway’s groundbreaking novels and stories and the complicated personality behind them are explored in “Rivers to the Sea.” Below, “Rivers to the Sea” writer and director DeWitt Sage shares some thoughts on the film:

Q: Can you tell us how this project came about?

Q: Can you tell us how this project came about?

A: AMERICAN MASTERS did a film that I directed and produced with Catherine Collins about F. Scott Fitzgerald. It was broadcast soon after September 11, 2001. And shortly after that we got a fax and a phone call from one Michael Katakis, who is the executor of the Hemingway estate. And I was ready for a blast, because if there was a villain of the Fitzgerald film, it was Ernest Hemingway. But not at all. They wondered if we would be able to do their “complicated character,” as they put it, and wondered if I would be interested in coming out to Bozeman, Montana, to meet Patrick Hemingway, the sole surviving son, and his wife Carol.

Believe it or not, I wasn’t lunging to do it because I was so exhausted after the Fitzgerald film, and also I hadn’t re-read any of Hemingway, but I was extremely curious. I said to Patrick that I thought I was “better at wimps than bullies,” meaning Scott rather than Ernest, and that I probably wasn’t the right guy, but I didn’t know, honestly. I was going to go back and do some re-reading. That was the late fall of 2001, and here we are a few years later.

Q: What was it like re-reading Hemingway in preparation for the film?

A: I hadn’t read Hemingway in any significant way since I was about 19, and I loved reading him then. But I had almost missed the key thing that he had written, which were his short stories. I came back [from Montana] and I read certain short stories — “Big Two-Hearted River,” “The Battler,” “Indian Camp,” “Snows of Kilimanjaro,” and “The Short Happy Life of Frances Macomber.” And because it was so short, I read a story called “A Cat in the Rain,” which is only two and a half pages and I think remains my favorite story of his. And there was also a story called “A Clean Well-Lighted Place.”

And I realized right away that I had misread Hemingway in the first place, and misinterpreted the core of his art, because he wasn’t writing action-adventure stories, which is what had led me to him at age 20. He was writing about surviving with some dignity the indignities of life. What gave me a hook for a possible film is the complete schism between the public image of Hemingway and the private subjects of Hemingway — what his fiction was about. I thought there was generally a dramatic disconnect, as there had been for me personally, and it made me want to get the true story out, starting with a boy, Nick Adams [from THE NICK ADAMS STORIES] who was afraid of the dark.

Q: What effect did Hemingway’s early life have on his writing?

A: Well, this part is not in the film, but Ernest, for whatever biological, cultural, or environmental reason, as a child was extremely sensitive to pain. Now, I have a theory that is probably not worth the paper it’s NOT written on, because I’ve never written it down, but I do think that his father — Clarence Hemingway, who was a doctor, and whom he adored — had a fierce temper, and he whipped the kids quite brutally, from what I’ve read from Ernest’s older sister’s diary. And I think that at least it’s a possibility that these rages that would come across his father, and subject Ernest to whippings, might have been an aspect of why he was so sensitive to the sudden indignities of life. But I don’t know. That really is conjecture, and it didn’t make it into the film.

But on pain and on childhood, and early experience, the most dramatic thing that happened to Hemingway was that he was severely wounded in World War I. And I agree with what Ann Douglas, a professor at Columbia, says in the film, that he got away with his life and he also got away with material he would use for the rest of his life. I think this is true, but I don’t think it was an affirmative experience. I just think he was a born writer who somehow sensed that he had great material here to work with. Many great writers are the same. His grave wound gave him material and sensitized him, but he was already going to be a writer. It didn’t make him a writer, despite distinguished theories to the contrary.

Q: Do you have any interesting anecdotes about the filming?

A: We got detained while we were filming in Havana. There were two rather large security guys who showed up at the hotel and said, “You are to stop filming, you are not to leave the hotel.” We didn’t know what was going to happen, and we indeed did stop filming and we didn’t leave the hotel. So we were under house arrest, but in the most glamorous circumstances. I sent a telegram back to WNET saying, “Sage and Hemingway crew detained,” simply trying to get sympathy and add drama to the production, but I don’t think I succeeded. It was very dramatic when it happened, but we’d gotten our filming done in four and a half days, and we were allowed out with the footage. I was very worried they weren’t going to let us out with the footage. And now Ernest’s home away from home resides in the editing room.

Q: Can you describe your production process, or how you chose to shoot the film?

A: The medium of film allows us to incorporate many different art forms to get the story across: music, cinematography, sound effects, all very important. Film can cast a spell and make you feel and believe temporarily, even though you know you’re looking at a screen, that you’re in, emotionally, another time and place. And I think that’s true for documentary as well as for fiction film. This is really about Hemingway’s fiction and life condition. It’s not a chronology of his life. I want to try to engage the emotions of the viewer, and so that’s why I always try to avoid driving a story with hard facts, chronology, or heavy information. In fact, I always try to avoid even having a narrator.

Q: So it was a very conscious decision not to use a narrator in RIVERS TO THE SEA?

A: Yes. There are 26 characters in the film, all of whom are voices, but there’s no external “voice of God” narrator. Also, this film, much more than the Fitzgerald, seemed not to want to have many expert commentators either, so there are very few of those. It’s more the people that knew him, either on camera or through their voices as performed by actors.

Q: Is there one thing you’d like viewers to take away from the film?

A: I think if the film works, a) you won’t get bored; and b) you’ll be reintroduced to an artist whose work you might consider well worth reading with a new insight. But I just would be excited if people have an engaged emotional experience learning about someone they thought they knew about, or emotionally just getting a perspective about someone who is sort of a lifeless icon.