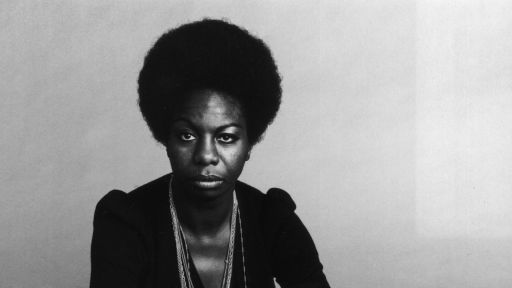

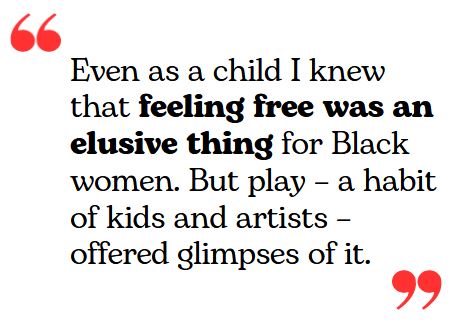

“I wish I knew how it would feel to be free.”

We sang Nina Simone’s song at my Quaker school in Massachusetts. And I played it repeatedly on the record player in the apartment I shared with my mother, a small warm retreat filled with the sounds of the Black South and books about Black liberation and novels that told the stories of Black women’s lives. Even as a child I knew that feeling free was an elusive thing for Black women. But play – a habit of kids and artists – offered glimpses of it.

Sitting on the floor, I often wrote stories in the small white margins of Ebony Magazine alongside celebrity photographs. My short works of fiction were about dynastic families full of melodrama and deep love. Though there were images of Black people on TV by then, “Good Times” and “The Jeffersons,” I always wanted more – more than drawings alongside the prose I wrote breathlessly, often misspelling words written with backwards letters. I wanted to see the people I dreamed up and make their lives magnificent; to merge images with my dreams.

The image makers are always consequential.

Popular culture is integral to the social order, and also its transformation. In American history, demeaning images of Black people: bug eyes, distended mouths wide enough to consume a whole chicken at once, shuffling and scratching, were once ubiquitous. Even now, long after the consensus about their racism has been set, we see recurrences of stereotypes and caricatures in images. For Black women in particular, the images that demean insult us for being inadequately “woman” and inferior because we’re Black.

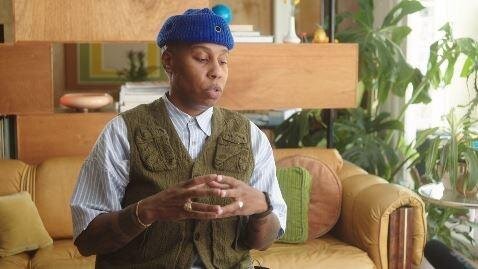

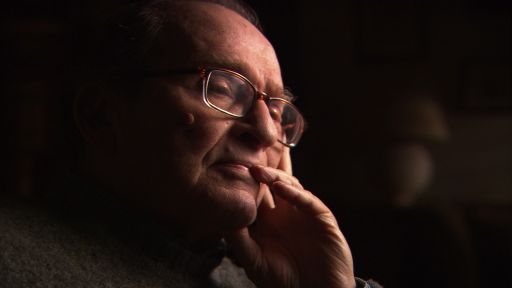

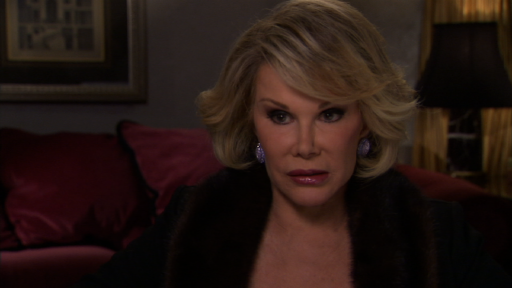

How it Feels to be Free explores this dynamic through histories and lives of Black women performers. Contemporary critics, actors and musicians reflect on the impact of their predecessors in these endeavors. Nina Simone, Lena Horne, Cicely Tyson, Diahann Carroll, Pam Grier and Abbey Lincoln’s lives and work are featured. Re-encountering these women in this documentary – all iconic, each celebrated in her own way – and experiencing them together is nostalgic, but it is also an illumination. Each faced this truth: Black women had been cast as the opposite of ladies, in more than one way. No Black woman could be Scarlett O’Hara, and no one could care about Mammy or find her desirable in any way. Neither was true, despite what the screens said.

Artists as well as civil rights organizations fought against the Black image in the white mind and on the celluloid screen.

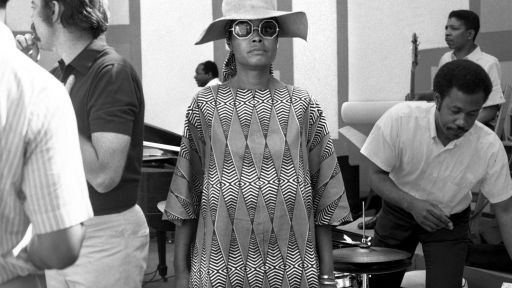

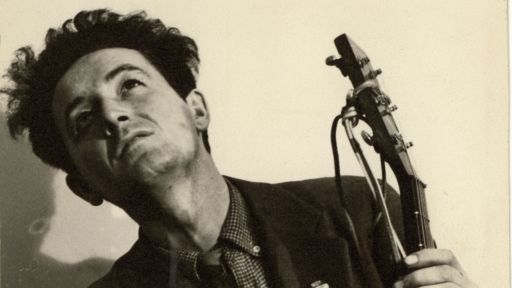

The recognition of the beautiful Black ingenue and chanteuse was hard earned as evidenced in the work of actresses Lena Horne and Diahann Carroll, and singer and musician Abbey Lincoln. Even after being acknowledged for both skill and beauty they faced another set of challenges. The perils of palatability, and in particular beauty, were felt when they shared their intellects and politics. Lena Horne and Abbey Lincoln each suffered under McCarthyism.  As they kicked over the idol versions of themselves, proving that they were not dolls, not icons, they faced a backlash, especially Abbey Lincoln. I first found myself thinking about Abbey Lincoln as a result of the brilliant work of literary, music and culture scholar, Farah Jasmine Griffin, who describes her, and the other Black women artists, in terms of their self-creation. Abbey Lincoln’s stage name was, of course, a play on the name of the president who was somewhat erroneously credited with “freeing the slaves.” She, too, wanted to free her people, and made her body and sound an expression of her pro-Black, anti-colonialist and feminist politics.

As they kicked over the idol versions of themselves, proving that they were not dolls, not icons, they faced a backlash, especially Abbey Lincoln. I first found myself thinking about Abbey Lincoln as a result of the brilliant work of literary, music and culture scholar, Farah Jasmine Griffin, who describes her, and the other Black women artists, in terms of their self-creation. Abbey Lincoln’s stage name was, of course, a play on the name of the president who was somewhat erroneously credited with “freeing the slaves.” She, too, wanted to free her people, and made her body and sound an expression of her pro-Black, anti-colonialist and feminist politics.

In the mid-20th century, Black politics and struggles were divergent.

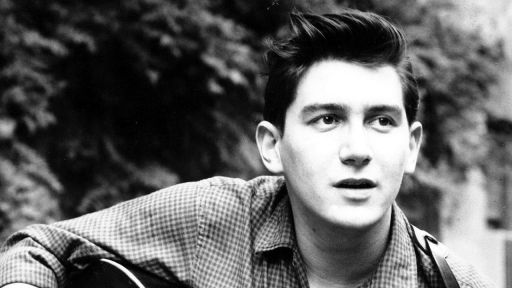

Some saw the struggle primarily in terms of being treated and seen as fully American. Diahann Carroll’s groundbreaking series, “Julia” (1968-1971) was an example of how that aspiration could be rendered in television. It featured a widowed Black mother who worked as a nurse and lived an elegant life. She and her son experienced racism, but race, generally speaking, was beside the point in her life. It was groundbreaking to see a “regular” life lived by a Black person. But the show raised ire in some quarters of Black America. The critics preferred for Black artists to bear witness to the distinctive struggles of Black life. It was not enough to say, “Black people are just like you,” it was also necessary to say, “Black people do not live in the America you know.” But even that assertion could be a source of conflict. Did that mean depicting the journey from slavery to freedom, as in Cicely Tyson’s star turn in “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” or the underbelly of urban centers as depicted in Pam Grier’s Blaxploitation films, part feminist triumph, part spectacle of sex and excess?

The truth is that images were and are as ambiguous and divergent as the visions for freedom.

To this day, impassioned debates over the meaning and impact of Black images and art persist. A universally agreed upon perfect representation isn’t possible. But I, and I suspect many others, agree with W.E.B. Du Bois’ formulation in his 1926 essay, “Criteria of Negro Art.” All art is propaganda, and Black art especially so.

I watched and heard all these women as a little Black girl. Their presences fueled my daydreams. As I grew, I learned that behind every image is an architecture. It’s built of money, power, resources as well as history, imagination and will. Knowing that makes what these women did and how they worked to reach freedom even more breathtaking and inspiring.