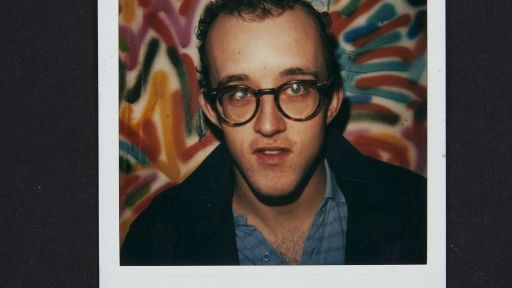

Keith Haring will forever be remembered as a prolific artist who shirked convention and elitism to bring art to the streets and its people. Lesser known is just how much Haring’s HIV diagnosis in 1987 helped propel the work of one of history’s best known street-artists-turned-AIDS-activists in the last two years of his life.

The early 80s was a period of sexual discovery and awakening for Haring and his friends in New York City, where Haring felt liberated to truly find himself, free from the constraints of his conservative upbringing. But this era was also marred by the introduction of HIV and AIDS—words that soon became synonymous with fear, stigma and death—that cut quickly and savagely through gay communities across America and the world.

The disease hit New York hard and fast. Diagnosis often followed the discovery of red or purple lesions on the face and body, a common symptom of the disease’s progression. As Haring and his circle saw more and more friends fall sick and then succumb to AIDS, it motivated them to keep creating with whatever time they had. “We got very myopic about creating, doing things […] I think in a lot of ways to avoid the trauma of seeing our friends die right and left,” said one of Haring’s close friends, Ann Magnuson.

Eventually, Haring would notice trouble with his breathing and found a purple splotch on his leg, leading to his own HIV diagnosis in 1987. Though it was a devastating blow to the then-29-year-old, Haring chose to confront the disease head on.

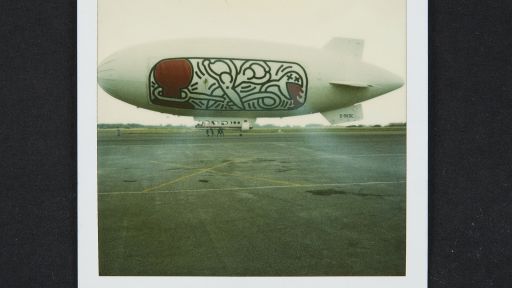

He was driven to new heights to create art more aggressively than before, even while he was traveling back and forth to doctors appointments and hospital visits. “Once Keith got his diagnosis he basically just ramped up everything, he just worked and worked and worked, and worked, and worked and he created so much art,” said friend Julia Gruen. “He traveled like crazy.”

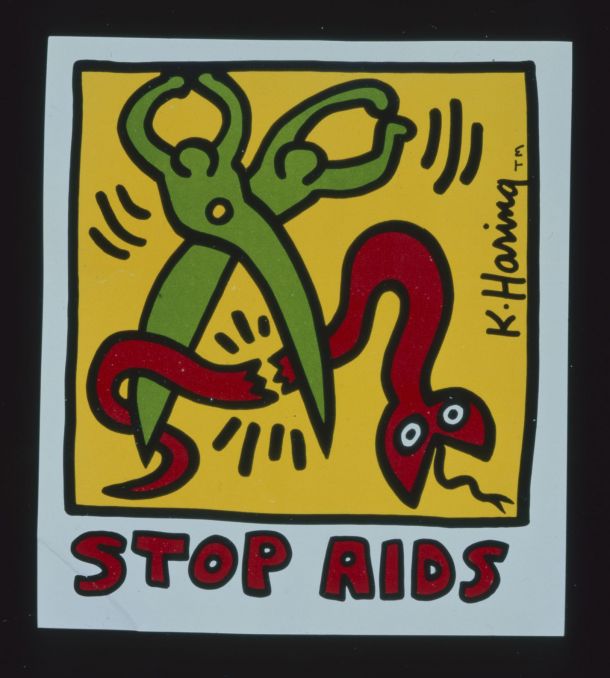

His work around this time included many paintings that depicted sex acts and phallic line drawings, which were used to create attention and awareness of HIV/AIDS, and to promote safe sex campaigns. Many other artworks contained “a great deal of darkness in them,” said Gruen.

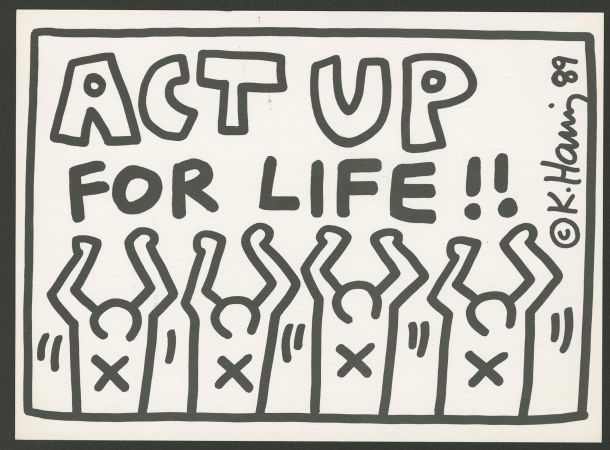

Haring was also a major supporter of HIV/AIDS awareness organizations like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). On numerous occasions, Haring offered tens of thousands of dollars to organizers to help pay for awareness actions, which he presented in huge wads of cash that he would pull out of his knapsack, according to activist Peter Staley.

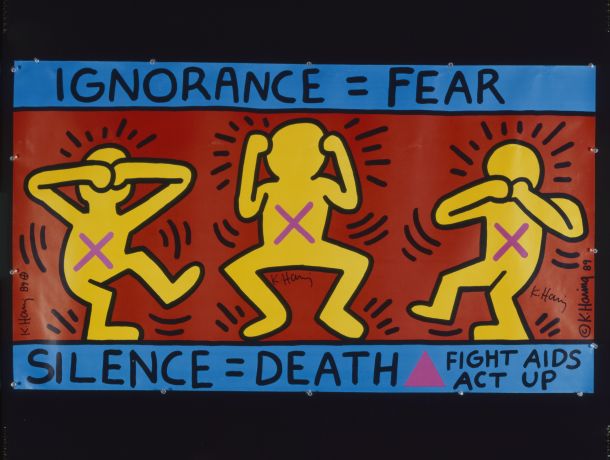

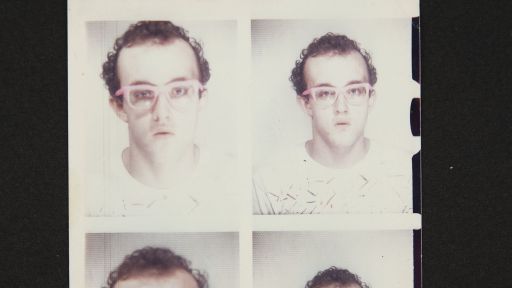

Two years into his diagnosis, Haring laid out his entire life story and what it was like living with HIV/AIDS in a 1989 Rolling Stone article, to challenge the silence and stigma surrounding the illness.

“There was hysteria and fear ’cause so many had it, yet nobody was coming out and talking about it; especially nobody famous,” said friend Kenny Scharf. “It was very brave of him to do that.”

Haring received both positive affirmations for his candidness about living with HIV, but was also shunned by many acquaintances and friends, especially in the celebrity world, where it seemed overnight, “the celebrity invites dried up,” according to Scharf.

Haring always had a lot of energy. He was creating and checking off long to-do lists daily, and oftentimes his friends said he spread himself too thin. “Even in the state he was, he was celebrating life up to the very end. In fact, he was celebrating it a bit too much, like I would say, ‘Keith, I would rather think it’s a good idea if you maybe ate healthy, have some of this carrot juice instead of doing a line of coke.’ And he’d be like, ‘F— that! You know I’m just gonna do this with the candle burning at both ends bright, and not wait for anything,'” according to Scharf.

Haring eventually died from AIDS-related complications in 1990 at the age of 31. He seemingly carried out his desire to make art accessible to millions of people right to the very end. The catalogue of work he created through his illness is among the estimated 10,000-plus pieces of art that would define his legacy for generations to come—which Haring himself predicted in a 1989 interview with his biographer:

“Those works that I’ve created are gonna stay here forever. There’s thousands of real people, not just museums and curators that have been affected and inspired and taught by the work that I’ve done,” he said. “So, the work is gonna live on long past when I’m gonna be here.”