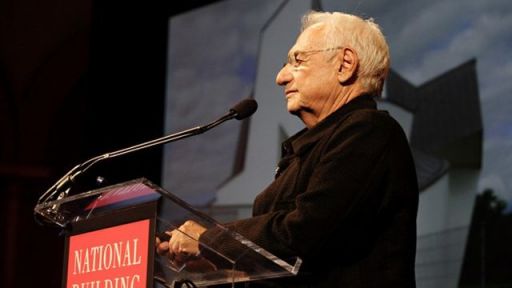

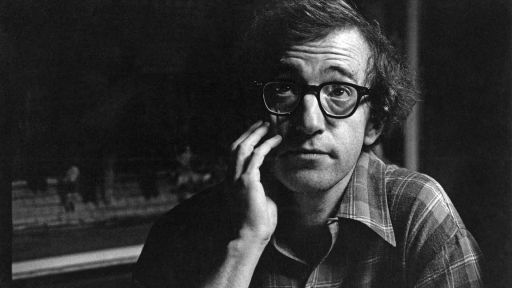

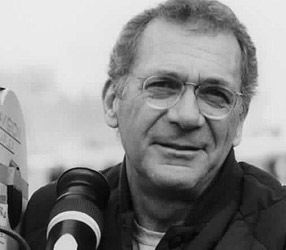

Throughout the course of an extraordinary career that began in the 1960s, Sydney Pollack has earned critical and popular raves as a director, producer and actor. With his first feature-length documentary, AMERICAN MASTERS Sketches of Frank Gehry, Pollack boldly enters new territory.

Throughout the course of an extraordinary career that began in the 1960s, Sydney Pollack has earned critical and popular raves as a director, producer and actor. With his first feature-length documentary, AMERICAN MASTERS Sketches of Frank Gehry, Pollack boldly enters new territory.

Q: When did you first meet Frank Gehry?

A: I met Frank in the early ’80s at a party. Frank was a part of a group affiliated with the therapist who’s in the documentary, Dr. Milton Wexler. The group consisted of very high achievers who were all artistic in some way. Some of them were directors, some of them were doctors, painters. I was not in the group but I did go to the parties sometimes and I met Frank that way. I think we hit it off because we were both big complainers. We complained about the difficulties of working in an arena where you were so dependent upon the approval of so many other people on whether or not you were successful. It wasn’t a question of how you felt about what you did, it was a question of how the world felt about what you did. And that that was tough. You know, we were feeling sorry for ourselves.

Q: How did this film come about?

A: Over the years I would bump into Frank or spend time with Frank and we would talk. We got to be better friends. And then I saw the museum in Bilbao on opening day and it rocked me. I was not prepared to have a physical object have that kind of emotional effect on me. In my past experience I hadn’t been that moved by architecture. It was a shock, even knowing Frank. Because as much as I liked him and as much as I thought of his work I hadn’t seen anything like that building before. I didn’t know where it came from in him, how it got born. So I got terribly curious about how it had come about.

Between 1997 and 2000, when I started working on the film, people were beginning to come to him to make documentaries. And he kept saying no, he was uncomfortable. Frank is a kind of shy guy, I think. The discussion came up about whether or not I’d ever made a documentary. To be honest, I don’t even know whether it was Frank that suggested it. Maybe it was somebody else. And I kept saying, “You’ve got to be crazy. I don’t know anything about architecture or anything about documentaries.” And Frank felt that that was a plus.

Q: Tell us about the actual production.

A: I had a real and burning curiosity to find out something for myself. It wasn’t a job. I had no deadline. I had no schedule. I had no form that I had to behave within. Frank was busier than I was so we just knew we were going to do this in our spare time, basically. The film got made over a period of five years – but at about one weekend or, at the most, two weekends a year. And on the year that I made THE INTERPRETER, I didn’t do anything on the film. It was a slow process. There were only two times that I worked over a large block of time. Once when I took a crew to Europe for two weeks to do all of the interviews in Europe and all of Frank’s European architecture. And then again when we started editing. But otherwise I would, let’s say, go and do Julian Schnabel in the morning and then spend the afternoon with Frank. And that’d be a Saturday. And then six months later I’d come back and do some more with Frank. Then six months later I would go and do a bit of the Disney building while it was going up.

Q: What makes Frank Gehry an American Master?

A: Innovation for one and an intensity with which he’s piqued the admiration and interest of the world. Certainly, you have to look at the fact that the world has become fascinated with Frank. He is a rock star all of a sudden.

Q: In the film you and Gehry compare filmmaking with architecture. What similarities or differences in the two arts struck you the most?

A: They’re both mosaic arts in that they’re comprised of many, many, many other art forms all put together like a big puzzle. When they’re successful, they have a pleasurable dreamlike element – the shape of a piece of sculpture, of a building, the way light hits it, the dream of a movie, the idea of a movie. But in order to achieve either you have to break it down into technical components, which are sort of mosaic in nature. In order to build the building you have to understand all kinds of physics. You have to figure out how to get people in and out of the building, how to get sewers in and where to put the loading docks, etc. If I want to make people moved or cry in a film, I figure out what the room looks like, what the people are wearing, what time of day it is, what the light is, how to photograph it, where to put the camera. It involves optics and costume design and set design and architecture.

Q: How did you manage to make static buildings not only watchable but beautiful? And what turned out to be your biggest challenge in filming something that doesn’t move?

A: If people find it beautiful to watch, and I’m not saying it’s true, but if it is true it could only be because that’s what I desperately wanted to do. I don’t know technically how I did that, other than to say that for all of the years that I’ve been doing this job a big component of it is visual. It’s impossible for me to go into a room or look at a location without a part of my brain photographing it – picking the best angle or looking at the way the light hits. I was trying to duplicate the emotional experience I had when I saw Bilbao. I was intensely moved by the beauty of it and the longing in it. There was something in it that was touching. It was a cathedral in some way.

The problem with filming something is that we struggle desperately to make three dimensions out of two dimensions. It can’t be done. In the beginning of this film I say I don’t know how to get this into two dimensions and Philip Johnson shakes his head and says, “It’s hopeless. You might as well give it up and become an architect.” It is kind of hopeless in a way because architecture is peripheral. What makes architecture extraordinary is that you’re looking at the building but your peripheral vision is also seeing how it fits within a space. And it’s seeing more than one part of the building at one time. You have no peripheral vision in photography and so we substitute a poor substitute, which is movement, to encompass it all, either tilting up and down or panning left and right, or a combination of the two. You try to get as much in as a tapestry. You concentrate on scale and shape and light.

Q: Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently?

A: If I had known this was going to be blown up to 35 millimeter and be shown on film screens I probably would’ve struggled to shoot in high definition. I shot with a very good camera, a wonderful little camera, but it’s not meant to be a professional camera. I wanted Frank to be completely relaxed and I didn’t want to go in there with a crew. I wanted to be as alone as I possibly could with him.

Q: How is documentary filmmaking different from feature filmmaking and would you do it again?

A: They’re both hard. I couldn’t make the comparison. The only thing I could say is that there was something liberating about doing this, about having fewer distractions, being able to work lean and free in a certain kind of way and follow an impulse. You can’t make a documentary happen the way you want because you don’t have any idea what you’re going to do. You go where the conversation goes, you go where the free associations go. And you really don’t know what you have until you edit. Would I do it again? Yes, of course. I would do it again providing I could find the same degree of curiosity and the need to know or want to know that I had with Frank.

Q: How do you respond to some critics of the film who say that it’s not objective enough, that it’s a valentine to a good friend?

A: Well, it is in a way. I wasn’t attempting to be critical. I wasn’t making the film as a job. I was being completely selfish. I have only one reason to make this film – because there’s a bunch of stuff I want to know about Frank. That’s what I went after. I didn’t see myself as a filmmaker. I didn’t see myself as a documentarian and I didn’t see myself as obliged to be either objective or subjective. I just felt that I wanted to give the audience a piece of Frank Gehry’s mind. I wanted to find out in my head what his process was like. Along the way I decided that I’d better include some people who didn’t like him. The only person I could find who would go on record was Hal Foster. We did use all those headlines, which were very derogatory. There’s a montage in which you see “ugly,” “grotesque,” “horrible.” There were other people who are not fans of Frank who I invited to be in the film but they declined. I happen to like Frank’s work. And I happen to love Bilbao. That was very clear. As for the rest, I was trying to get people to answer what it was about Frank that they either liked or disliked. And what it was that made Frank Frank.

Q: During the course of the filming what did you uncover about your friend that you didn’t know – and what did you learn about yourself?

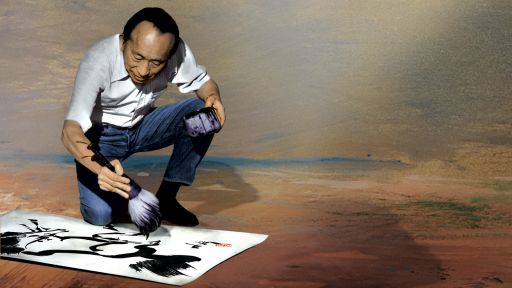

A: Everybody asks me that and I don’t have an answer for them. I discovered a lot, but I don’t know how to describe it. I had no idea what he did all day. I mean, he sits there and he looks at those models and he plays with things. He tries to think and then goes home and thinks. I feel like I do that too. I don’t have a model necessarily but I have toy soldiers in my head that are people.

What did I learn about myself? I learned that I could behave in a very dorky way sometimes. I didn’t expect to be in the film at all. I was very naive about documentaries and I didn’t realize that you can take a single point of view and just cut out the bad stuff and jump cut the film. I was proceeding the way I would in a feature film. The only way I could control it is to have another angle to cut to – that way I could drop material out or invert it or manipulate it. So I asked my producer Ultan Guilfoyle to always cover another angle on Frank. But Ultan kept shooting the two of us. When our very, very talented editor came in she started putting that footage in, all of it, and it became the two of us. I kept resisting that because I thought, you can’t do this, this is the height of narcissism. You can’t tell the story of a guy that you’re saying is an American Master and artist and then throw yourself in the middle of it. And Frank kept saying, “What I love about this is that we’re in it together, it’s a conversation – I’m not just being interviewed.” That turned out to be something that critics really responded to because it was a conversation between two old friends. That resonated.

Q: Is there a dream project you’ve yet to tackle?

A: Everybody wants to make a film that they think of as a perfect film. I certainly don’t feel like I’ve accomplished anywhere near what I would hope to accomplish. I still look forward to taking a whack at it again.