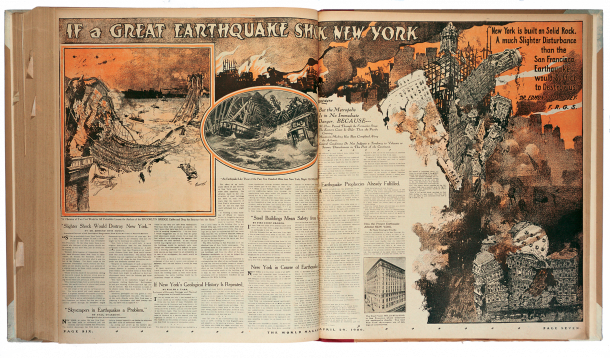

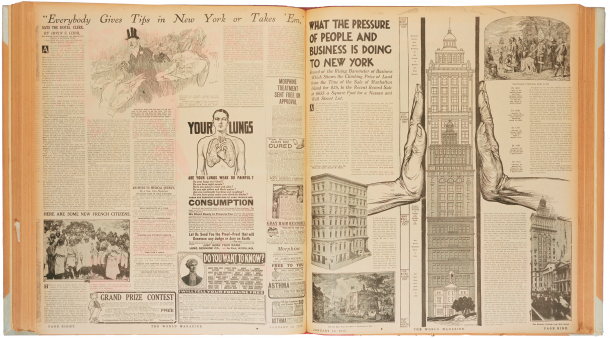

Spread from the World’s magazine section, Apr. 29, 1906, with art by Louis Biedermann. Courtesy David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C. Photographs by Nicholson Baker

Originally published in Art in America, May 2018. Copyright © ArtNews Media, LLC. Reproduced by permission.

I had a small paper which had been dead for years, and I was trying in every way I could think of to build up its circulation. . . . What could I use for bait? A picture, of course.

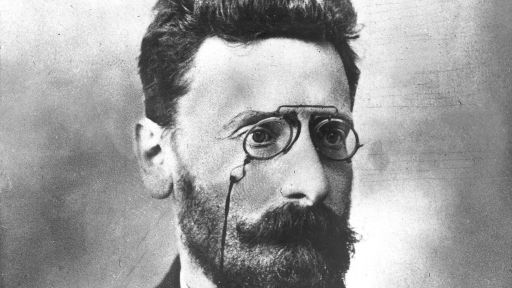

—Joseph Pulitzer

Giant hands squeezing a towering Manhattan building to demonstrate how high skyscrapers—and real estate prices—might soar; an apocalyptic vision of how a massive earthquake might devastate New York City; a page-filling view of whales cavorting around a submarine; a large centerpiece portrait of Mark Twain accompanying one of his short stories; a revelatory two-page spread on the Astor family’s real estate empire, headlined “It Would Line a Thoroughfare Seven Miles Long—A Brisk Walk of Two Hours Would Not Traverse It, Passing $15,000 Worth of Property at Every Step.” For over three decades, readers of Joseph Pulitzer’s turn-of-the-century newspaper, the New York World, were dazzled by the tabloid’s pictorial outpourings, which climaxed each week with the Sunday World.

During my scriptwriting research for a forthcoming “American Masters” television documentary on Pulitzer, I was struck by the newsman’s savvy appreciation of the communicative power of images.1 While many other publishers shunned investing in the costly, time-consuming process of printing multiple pictures each issue, Pulitzer transformed his daily into a visual cornucopia and, at its most sublime, an art form. In today’s terms, it was a commercial image-and-text project with a democratic—and demotic—social agenda.2

For the People

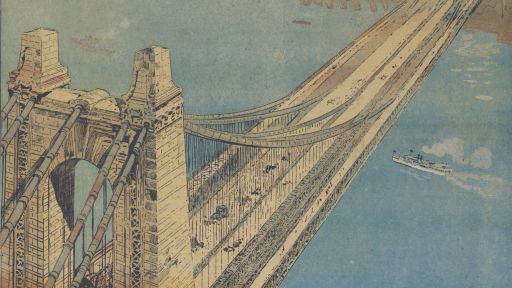

Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911) started his prodigious use of illustrations just ten days after buying the New York World in May 1883.3 To mark the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, he splashed a four-column image of the new structure across the front page. A headline proclaimed his challenge to the one-penny walkway toll: “Let the Bridge Be Free / A Penny Is a Workman’s Lunch.” Pulitzer’s campaign eventually led the city to rescind the pedestrian fee—and also led to “common” readers recognizing a fearless new champion. Within a year, Pulitzer’s paper became a megaphone for newcomers and the poor, styling itself the “Immigrants’ Bible” and the “Voice of the People.” Among the World’s many other populist undertakings was an 1885 solicitation drive that raised more than $100,000 (equivalent to around $3 million today), some of it from penny donations by schoolchildren, to fund the stone pedestal for the Statue of Liberty.

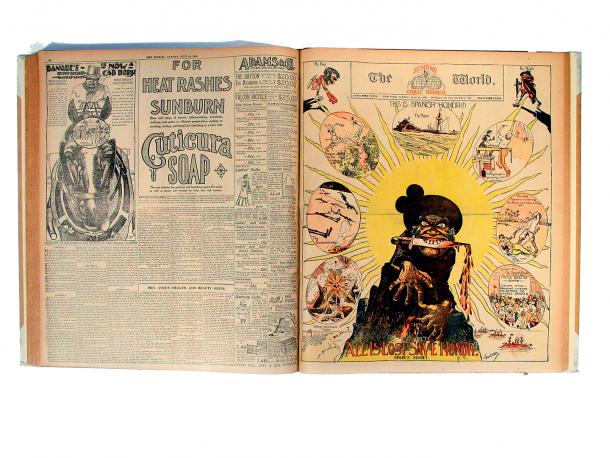

A page from the World’s magazine section, Jan. 16, 1910, artist unknown. Courtesy David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C. Photographs by Nicholson Baker

Pulitzer—himself a Jewish immigrant from Hungary who learned English as his fourth language—expended much thought on how to make the World accessible to as many people as possible. In an era of elaborate verbal constructions, he insisted that his reporters employ simple vocabulary and elementary syntax. The pages of the World also brimmed with useful information—from how to register to vote to ways to navigate public transportation, from where to hunt for ducks in New York City to how to apply for a job. Most noticeably, bold, innovative graphics and terse, snappy captions familiarized immigrants with the new language and strange folkways of American society.

To create striking visual material, Pulitzer hired caricaturists, illustrators, and painters, including Ash Can School artist George Luks. Although photographs increasingly appeared in the World and other newspapers during this period, the somber prints could not, given the cumbersome technology of the day, match the fluidity and flair—to say nothing of the color—of imaginative hand-drawn renderings. The World’s ever-expanding stable of graphic artists included many forgotten today but widely known in the Gilded Age. The inventions of Charles Green Bush, Kate Carew, J. Campbell Cory, Hermann Heyer, Walter Hugh McDougall, George “Jiggs and Maggie” McManus, R.F. “The Yellow Kid” Outcault, William J. Steinigans, Helen Stilwell, along with the prodigiously talented Louis Biedermann, a master of crowd scenes and bold aerial perspectives, were sprinkled liberally throughout the newspaper’s pages.

Pulitzer’s reformist politics and pictorial élan appealed to so many that his publication quickly became the country’s best-selling daily—and its first national newspaper. By the last decade of the nineteenth century, the World sold more than 800,000 copies each day.

Sensationalism

For just two pennies, the paper also provided insider access to secret worlds—from celebrity infidelities and high society scandals to titillating transgressions in basement opium dens. Articles were introduced by a barrage of lurid headlines: “Baptized in Blood,” “A Fiend in Human Form,” “Let Me Die! Let Me Die!”There were bizarre features like “Treatise on Recent Murder Weapons,” with depictions of the lethal implements themselves: a nail, a coffin lid, a teakettle, a matchbox, an umbrella, a red-hot horseshoe, even a blood-soaked scrub brush. When one particularly grisly murder occurred, the World printed illustrations of several barrels, complete with directional arrows indicating that the victim’s head was contained in Barrel A, the legs, in Barrel B, and so on, anatomically.

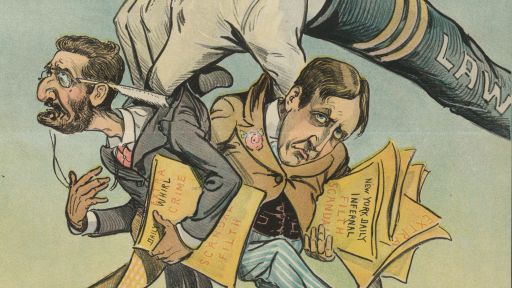

Pulitzer’s paper was deemed so transgressive that it was banned by the Young Men’s Christian Association as well as by certain upper-class social clubs. One rival journal lamented:

Pulitzer has made The World a sewer for the stream of vice and filth which courses through the great city under the surface of decent life.4

The World replied:

The daily is like the mirror. It reflects that which is before it. . . . Let those who are startled by it blame the people who are before the mirror, and not the mirror, which only reflects their features and actions.5

Cover of the World’s women’s weekly section, Feb. 13, 1898, showing art by Ed Williams. Courtesy David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C. Photographs by Nicholson Baker

The true horror was that Pulitzer’s paper did not have to up the ante by writing fiction about squalid living conditions. Many of his reporters were hardcore realists, publishing facts that the genteel classes resented reading. New York streets were filthy—two and a half million pounds of horse manure had to be removed each day. The city suffered from terrible residential congestion—in one five-square-block area, a population of thirty thousand (these days, the average is 27,000 per square mile). Housing stock for the poor was wretched, with people jammed into airless tenements. In summer, to escape stifling apartments, many slept on rooftops, which led inevitably to accidental deaths as adults made missteps in the dark and children plunged off unfenced roofs.

Politics and Other Crimes

The World printed a vast array of investigative stories and political cartoons, attacking the malfeasance of politicians and robber barons, of exploitative factory owners and the Democrat Pulitzer’s frequent target, the Democratic machine’s Tammany Hall. Championing the underclass polished the publisher’s image and sold papers. The World proclaimed:

Virtue ought to rejoice that the press acts like an argus-eyed conscience . . . [and] prevents immorality from becoming general by preventing it from being hidden. . . .

There is nothing that wrong doing so much desires as to be let alone. But it never has been since the printing press got fairly in motion.6

Pulitzer, a Union Army veteran of the Civil War, waded into national politics as well. During the presidential campaign of 1884, only a year after purchasing the paper, he caused an electoral firestorm by printing, on the front page, Walt McDougall and Valérien Gribayédoff’s caricature The Royal Feast of Belshazzar and the Money Kings. The image places James M. Blaine, the Republican presidential candidate, at a banquet table surrounded by eighteen wealthy donors—among them the financiers and railroad magnates William H. Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Russell Sage, and Chauncey Depew. The oligarchs sup on “Monopoly Soup,” “Navy Contracts,” and “Lobby Pudding,” while, in the foreground, a father, mother, and their bewildered daughter beg the indifferent plutocrats for table scraps.

The illustration—related both to ubiquitous nineteenth-century depictions of economic misery and to a long tradition of vicious pictorial satire that includes artists like Honoré Daumier and Thomas Nast—became one of the most consequential visual statements ever to appear in an American journal.7 In a bitterly fought race, not decided until the last ballots were counted, the Democrat Grover Cleveland beat James G. Blaine by a thin margin to carry crucial New York State and, with it, the national election. Pulitzer’s earlier boast to his staff that he could indeed help “make a President” had come true: Cleveland’s victory ended six straight terms of Republican control of the White House. The implications of that claim for American democracy seem not to have troubled him.

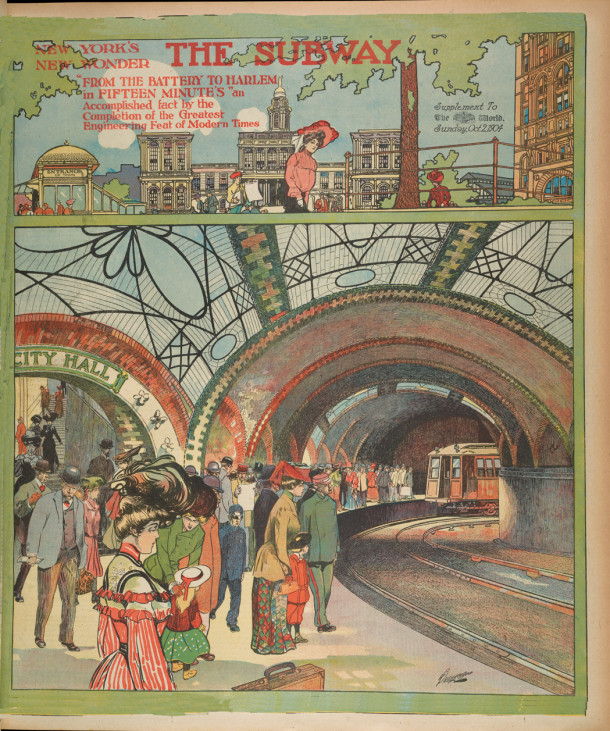

Cover of the World’s subway supplement, Oct. 2, 1910, with art by Louis Biedermann. Courtesy David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C. Photographs by Nicholson Baker

The World also held that its dissemination of visual evidence could help solve, and even prevent, everyday forms of crime. One example: a Manhattan stockbroker named Johan Eno embezzled $20,000 and disappeared. That is, until a Montreal cop spotted the thief because of a Joseph Keppler portrait reproduced in the paper. After Eno was extradited and tried, the World published Keppler’s likeness, trumpeting him (and the paper that employed him) as the era’s most up-to-date crime stopper: “Portrait Nabs Miscreant in Quebec, Canada!”

Crime of another sort was famously exposed by reporter Nellie Bly, who in 1887 went undercover as a patient in the women’s hospital for the mentally ill on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). In an outcome that would have pleased any New Journalist of the 1960s or ’70s, Bly’s illustrated first-person account of abuse in the East River asylum, published serially in the World and later as the book Ten Days in a Mad-House, spurred a grand jury investigation and an $850,000 increase in the budget of the Department of Public Charities and Corrections—$60,000 of which went to the asylum.8

Technological Romance

Pulitzer was an early adopter of technological change. To keep pace with New York’s burgeoning population, he purchased state-of-the-art R. Hoe rotary presses. The new mechanism was so fast and capacious that it used a continuous roll of paper five miles long. The press could print, paste, fold, and bundle up to twenty thousand copies of the eight-page newspaper per hour.

Along with a sea of images, every edition of the World offered a cunning mixture of progressive politics and self-promotion. The daily even headlined its surging sales figures on its front page: “The World’s Circulation Over 5,000,000 Per Week / Largest Circulation of Any Newspaper Printed in Any Language in Any Country.”

Pulitzer’s strategy was intended to increase advertising rates—and did. The Worldhad an in-house design staff that worked with advertisers to invent enticing graphics, the pictures often slicing columns horizontally or vertically or both. Department stores spent vast sums, offering sales and discount coupons on which the paper’s designers lavished their visual skills. The two institutions—Pulitzer’s journal and mega-emporia such as Macy’s, Gimbels, and A.T. Stewart & Co.—grew simultaneously and symbiotically.

Sunday was the day of days for Pulitzer’s publication. For one nickel, New Yorkers of all ages could immerse themselves from dawn to dusk in the thick, user-friendlyWorld. Reader engagement, always a key factor, was prompted by such highly addictive diversions as the first American crossword puzzles. Pulitzer even strove to make his ink-and-paper medium leap off the page into three-dimensional reality. The Sunday World contained a variety of hands-on attractions—including paper cutout toys for the kids and a primitive moving-picture device that could be cut out and assembled. Dress patterns were a favorite, allowing housewives to copy the latest Parisian styles. Sheet music for popular tunes facilitated home entertainment. The range of activities brought the entire family into the World’s fold.

Comics and Color

Then there were the comics. The artist/illustrator J. Campbell Cory once identified the unique role of his art:

The cartoon . . . is the most powerful instrument . . . that is permitted to exist under the sacred and inviolable protection of the ‘freedom of the press.’ The cartoonist may express what the editor dare not write.9

By the early 1890s, Pulitzer was nearly blind, seriously ill, and wandering Europe in search of cures for his multiple ailments. Nevertheless, though he ran the paper largely by telegram, he managed to transform it in absentia: color printing had arrived in the pages of the World. Never reluctant to treat itself as the story, thepaper festooned self-congratulatory copy across its own pages: “Like rainbow tints in the spray are the hues that splash and pour from its lightning cylinders.”10

The verve of that promise highlights the nature of Pulitzer’s entrepreneurial talent. He did not invent illustrated newspapers, comic strips, or the liberal use of color. But scanning the field of competitors, he recognized clearly and decisively what editorial elements would appeal to the World’s audience (current and potential) and then delivered them to his readers with all-out enthusiasm and panache.11

On May 5, 1895, for example, the artist R.F. Outcault introduced a striking single-panel cartoon that mimed the gritty realities of working-class life. Set in the cramped space between tenements, Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley” was bursting with New Yorkers—women and men leaning out windows, sitting on stoops, and hanging off fire escapes, commenting, kibitzing, arguing. Each installment brought events like slapdash parades and political spats and footraces, all reflecting the rich flux of late nineteenth-century life on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Invariably, the scene featured a jug-eared, odd-looking street waif with a perpetual grin. The Yellow Kid had nary a hair on his head and was enveloped in a flowing canary yellow nightshirt. Though he looked moronic, the boy offered wry, insightful comments about the teeming existence of the city’s poorest.

One early panel depicts the Kid playing poker with his youthful sidekicks. His internal monologue is printed on his smock, prefiguring the “thought balloons” that would become a universal staple of comic art. The streetwise anarchist holds four aces in his right hand, while a fifth peeks out of a capacious yellow sleeve. A sixth ace lies on the floor by his right foot, and in the background, a boxing match is under way. In the panel, Outcault captured the simultaneity, confusion, and lawless clamor of the nonstop metropolis. New Yorkers of all income levels, from upper Fifth Avenue all the way down to the Battery, gabbed about the Kid’s colorful, slang-drenched exploits. So successful was the character that Pulitzer’s major competitor, William Randolph Hearst, bought Outcault away for his own New York Journal staff. The term “yellow journalism” soon emerged in reference to the Kid, disparaging the sensationalist, proletarian style of the newspapers that featured him.

Cover of the World’s weekly comics section, July 24, 1898, with art by George Luks. Courtesy David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C. Photographs by Nicholson Baker

War and Peace

Certainly the approach had serious drawbacks, as readers now—in the age of Rupert Murdoch, People magazine, TMZ, and “fake news” both real and truly fake—are all too painfully aware. Going beyond staff poaching and price duels, the rivalry between Pulitzer and Hearst fed a jingoistic fervor that welcomed, and was a factor in precipitating, the Spanish-American War.

Closer to home, greedy capitalists may have been a constant editorial target, but both moguls conducted their distribution business ruthlessly in the face of the 1899 newsboys’ strike. And both, ironically, were forced to negotiate with the exploited street hawkers, backed as they were by Pulitzer’s everyday paper-buying “people.”

Nevertheless, Pulitzer’s legacy remains, on balance, commendable. His illustrated daily, engagingly crass and dynamic, was one of the many popular publications that inadvertently spurred the breakdown of the long-held distinction between “high” and “low” art. Indeed, the World’s visuals anticipated twentieth-century artists’ voracious appetite for subjects untreated by their predecessors. Think, for instance, of Picasso and Braque’s Cubist incorporations of the detritus of contemporary popular culture—tickets, theatrical programs, advertisements—or the generative effect of comics and mass advertising on Pop art, California Funk, Chicago Imagism, and individual artists from Peter Saul to Takashi Murakami. Part of the modernist revolution was the assertion that all subjects are potentially worthy of artistic treatment. The World was one of many instruments responding to the timeless urge of common people to be heard, informed, and entertained—a tendency greatly enhanced, not long ago in historical terms, by the invention of the printing press and the triumph of such “vulgar” forms as the novel and movies.

The immigrant Pulitzer realized that visuals could provide a bridge to literacy. He quickly fathomed that people learned in multiple ways, that education could come through pictures and hands-on activities as well as through traditional reading and listening. He passionately defended the right and duty of the press to print—and unabashedly promote—whatever it finds to be true. Love the World or hate it, Pulitzer’s visually saturated communication methods still flourish today—not only in tabloids and mass-circulation magazines but on television, the internet, and the glowing screens of our digital devices.