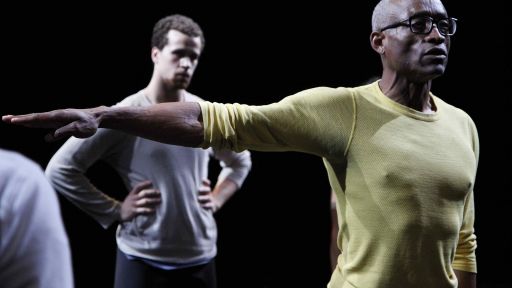

I didn’t want to move or act like a rich man. I wanted to dance in a pair of jeans. I wanted to dance like the man in the streets.

I didn’t want to move or act like a rich man. I wanted to dance in a pair of jeans. I wanted to dance like the man in the streets.

– Gene Kelly

Timeless, effortless, elegant and indelible as the 50th anniversary of Singin’ in the Rain approaches, Gene Kelly’s body of work still thrives and still thrills. With films that also include An American in Paris, Summer Stock, On the Town and Brigadoon, Kelly revived the movie musical and redefined dance on screen, bringing with him an inspired sensibility and an original vitality. His choreography and his performances were relaxed but compelling, innovative but highly accessible and, ultimately, magical. He endeared himself to audiences and had a profound, eternal impact on the craft. Among the most beloved stars of Hollywood’s golden age, Kelly’s career remains one of the most surprising.

Solely responsible for creating a new approach to film musicals as performer, as choreographer and as director Kelly’s story has never been fully told. A creative genius fueled by single-mindedness, a volatile temper and narcissism, his need for perfection was uncompromising. A lasting influence in the worlds of film and dance, his first major film success came at the age of thirty and a short ten years later, he had made his final hit film.

At odds with MGM throughout his time there, Kelly fought to expand the concept and reach of motion picture musicals, always keenly aware that he was beginning his film career well past his prime as a dancer. By the mid-1950s, Kelly found himself at loose ends the genre he helped master now over a victim of changing musical tastes and economic restrictions. Gene Kelly: Anatomy of a Dancer offers a far more incisive view of the graceful and charming, beloved entertainer than that which the world has come to know.

Gene Kelly’s early life

Born in 1912 into a large middle-class Irish family in Pittsburgh, Kelly’s father was a traveling record salesman and his mother was possessed with a formidable determination to expose her children to the arts. By his teenage years, Gene and his brother Fred took over a failing dance school with their mother and their father slid deeper into alcoholism. After choreographing local shows and playing nightclubs with Fred, by 1938 Kelly felt he was good enough to buy a one-way ticket to New York City and eventually won the lead role in the original Broadway production of Pal Joey.

Gene Kelly’s start in Hollywood

Seeing him on stage, MGM head Louis B. Mayer assured Kelly that the studio would like to sign him without so much as a screen test but, through a series of miscommunications, a screen test is requested and Kelly refused. Writing an acerbic letter to Mayer accusing him of duplicity, Kelly turned down the counteroffer and set the stage for a lifetime of acrimony between the two men. Ironically, Kelly was put under contract at Selznick International by Mayer’s son-in-law David O. Selznick, who had no interest in producing musicals and thought Kelly could exist purely as a dramatic actor. With no roles forthcoming, Kelly was loaned out to MGM to co-star with Judy Garland in For Me and My Gal. The film was a hit and Selznick subsequently sold the actor and his contract to MGM.

A series of mediocre roles followed and it was not until Kelly was loaned out to Columbia for 1944’s Cover Girl, with Rita Hayworth, that he became firmly established as a star. His landmark “alter ego” sequence, in which he partnered with himself, brought film dance to a new level of special effects. With Stanley Donen as his assistant, Kelly created a sense of the psychological and integrated story telling never before seen in a Hollywood musical. Realizing what they had, MGM refused to ever loan him out again, ruining Kelly’s opportunity to star in the film versions of Guys and Dolls, Pal Joey and even Sunset Boulevard. Back with producer Arthur Freed at MGM, Kelly continued his innovative approach to material by placing himself in a cartoon environment to dance with Jerry the Mouse in Anchor’s Aweigh yet another musical first.

Gene Kelly’s politics

During his marriage to the actress Betsy Blair, Kelly was radicalized and the couple became well known for their liberal politics. In 1947, when the Carpenters Union went on strike and the Hollywood studios were looking for an intermediary to intervene on their behalf, Kelly was chosen much to everyone’s surprise. He traveled back and forth from Culver City to union headquarters in Chicago for two months, mediating a strike that was costing the studios dearly. When a settlement was finally reached, Kelly was shocked to learn that the studios felt it was unfair and that they had been cheated by his siding with the strikers. Naively and genuinely trying to help and unaware of unstated expectations, underhanded tactics, and slush funds Kelly’s efforts only resulted in further exacerbating his relationship with Louis B. Mayer.

As the Blacklist Era began, Kelly along with Humphrey Bogart, John Huston, Danny Kaye, and others joined the Committee for the First Amendment. Hoping to diffuse the rising situation in Washington, DC, the group created a kind of whistle-stop national tour to present their views to the public prior to their command performance before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Their efforts and press conference deteriorated into a fiasco and forced many of the stars to return to Hollywood and focus more on personal damage control than on their original idealistic intent.

Gene Kelly and the musical era

More mediocre roles in “revue” films followed and Kelly’s frustrations mounted. He was, however, able to continue refining and showcasing his unique appeal and approach to new material with standout numbers in The Pirate and Words and Music, among other films. Determined from the start to differentiate himself from Fred Astaire, Kelly concerned himself with incorporating less ballroom dancing and more distinctly American athleticism into his choreography. Easter Parade and the chance to co-star with Judy Garland would have been Kelly’s opportunity to get away from what he considered substandard fare. But, in a show of bravado in his own backyard, Kelly broke his ankle during one of his infamously competitive volley ball games and, ironically, had to turn the film over to Fred Astaire.

Finally, Kelly and Stanley Donen were assigned their own film to co-direct 1949’s On the Town. In just five days of shooting selected sequences, they opened up the genre as no one had ever done before, creating another first a musical film shot on location. Followed by his two masterworks, An American in Paris, with its 17-minute ballet sequence, and Singin’ in the Rain, Kelly achieved icon status at the age of forty. In 1951, he was awarded a special Oscar for An American in Paris for his “extreme versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, but specifically for his brilliant achievement in the art of choreography.”

And then the shift began. The musical era, as well as the Freed unit at MGM, wind to a close and Kelly’s last productions, including Brigadoon and the ambitious It’s Always Fair Weather, failed to appeal to either critics or the public. The latter film also brought a bitter end to his partnership with Stanley Donen. The two had made history together in their three previous films the only successful directorial collaboration in Hollywood, before or since. But professional and personal conflict lead to the breakup, including the fact that Donen’s wife, Jeanne Coyne, had fallen in love with Kelly. With Kelly’s own marriage to Betsy Blair in dissolution, both couples divorced and Kelly eventually married Coyne in 1960.

Small roles and directing jobs followed. Professional highlights included the Broadway musical “Flower Drum Song” and an original ballet he created for the Paris Opera. In the late 1950s, the television show OMNIBUS invited Kelly to create a documentary about the relationship between dance and athletics Dancing: A Man’s Game is considered one of the classic treasures from television’s golden age. However, the hit Kelly so badly craved and needed as director of the film Hello Dolly, eluded him, unable to compete in a market that now included such movies as Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider.

Gene Kelly’s legacy

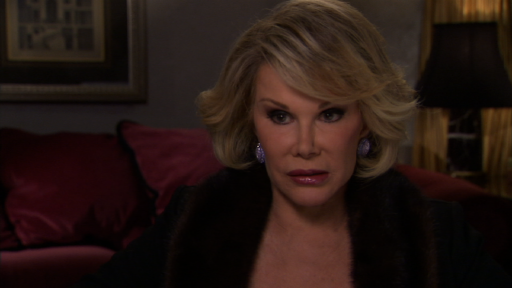

Jeanne Coyne died of leukemia in 1973, leaving Kelly to raise their two young children alone. In his determination to be a better father than he had been to his first daughter, Kelly refused all work that would take him away from Los Angeles, including the offer to direct the film Cabaret in Munich. He tried series television, guest appearances, children’s records and became a frequent advisor to younger filmmakers who were hoping to resurrect the movie musical. At his death in 1996, it was said of Kelly, “Just as he confirmed his place as one of the most important talents ever to work in film, he went downhill so fast you hardly saw him go.”

Yet, the potency of Kelly’s gifts, his remarkable achievements in dance and choreography and the creativity and charisma with which he exploded in a handful of films continues to endure and to inform. Gene Kelly’s final filmed words are from 1994’s That’s Entertainment III quoting Irving Berlin, he remarked: “The song has ended, but the melody lingers on.” And, so too has Kelly himself. He was number 15 on AFI’s millennium list of most popular actors and Singin’ in the Rain has been voted the singular most popular movie musical of all time.