Author and journalist Abby Ellin reflects on the legacy of Groucho Marx—acknowledging his brilliance, shortcomings and influence on a new generation of female comedians.

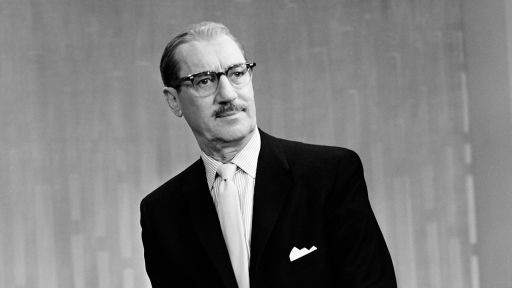

Groucho Marx was, above all else, an entertainer.

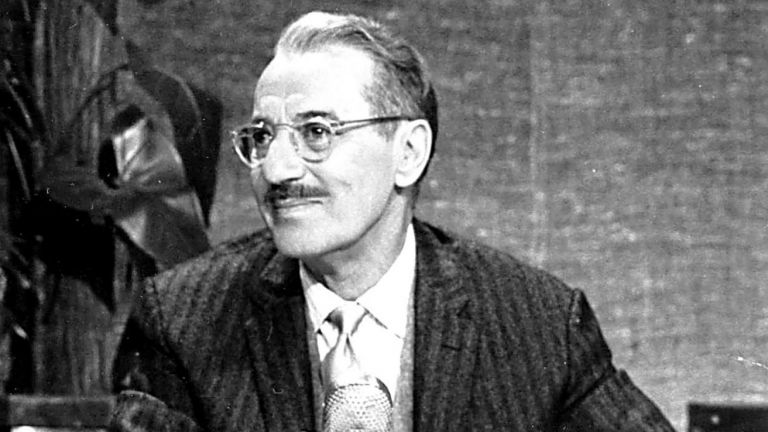

He sang. He told stories. He wore ridiculous hats and even worse, toupées. It’s impossible not to appreciate his verbal gymnastics and facility with language. He could express an entire megillah with a simple eyeroll.

When Groucho Marx passed away in 1977, a cancellation meant ending a subscription to the Sears catalog. But it’s a different world today. While there’s no more catalog, canceling has taken on a completely new meaning. And so it’s hard not to wonder how the cigar-chomping, bushy-browed, mustachioed Marx would fare today. Would he be forced to amend his language and behavior, and tamper his proclivity for women young enough to be his granddaughters?

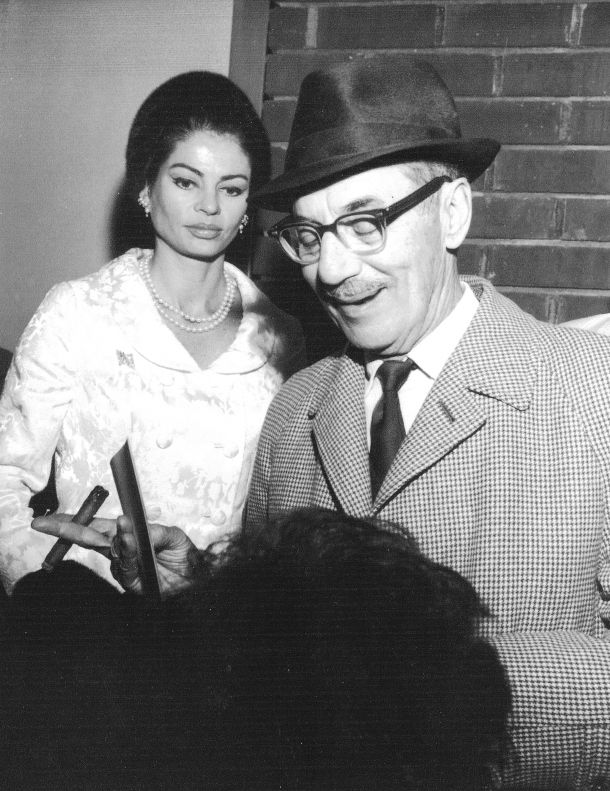

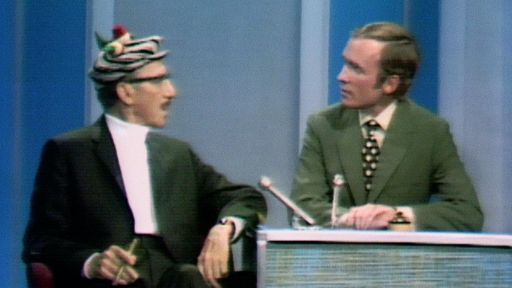

They’re good questions. Because let’s face it: Brilliant though he may have been, Groucho was notorious for breaking boundaries and insulting people, in character, certainly, and in real life as well. He had three wives; the older he got, the younger they got. During his 11 seasons as host of the comedy quiz series “You Bet Your Life,” he flirted and ogled and double-entendred his way around comely young female contestants in tight-fitting sweater sets. The joke, of course, was that he was a harmless old codger, an impish prankster just having fun.

But as his late daughter, Miriam Marx Allen, the oldest of his three children, said in the 1991 documentary “The One The Only Groucho,” “He liked to pal around with women, but he was sexist.”

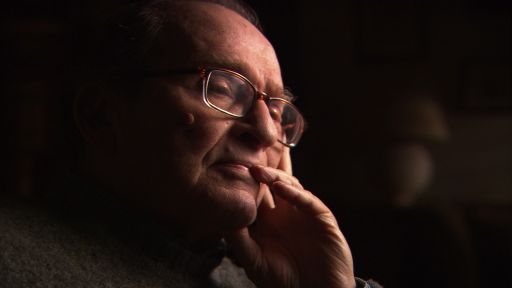

Steve Stoliar, who worked for the comic from 1974 until Groucho’s death three years later, corroborates this. “He married women he could dominate,” said Stoliar, author of “Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho’s House.”

Groucho’s characters thrived on insults, especially against women. One of his frequent foils was Margaret Dumont, his straight woman in seven Marx Brothers films, including “Animal Crackers,” “A Night at the Opera” and “Duck Soup.”

A sample exchange:

Groucho (as Rufus T. Firefly): Not that I care, but where is your husband?

Dumont (as Mrs. Teasdale): Why, he’s dead.

Rufus T. Firefly: I bet he’s just using that as an excuse.

Audiences ate it up, though not everyone finds it funny today. “His misogyny is relentless and thoroughgoing, and it’s very hard to tolerate,” Lee Siegel, author of “Groucho Marx: The Comedy of Existence,” told NPR.

But the reality is that this was simply the way the comedy world was at the time. “Groucho was structured by the world he lived in as are we,” said film critic Brandon Judell, a lecturer in the Department of Theatre and Speech at The City College of New York.

Before the 50s, stand-up comedy was the purview of men.

Mother-in-law jokes were di rigueur; women—fat women, thin women, ugly women, gorgeous women, women who could whip up a tuna casserole in five minutes and women who burned water—were fair game. (Even animated characters got in on it: Bugs Bunny, impersonating Groucho, tricks Elmer Fudd in a satirical game show called “You Beat Your Wife.”)

It wasn’t until a 37-year-old mother of five who looked like she’d collided with a clown and a lightning bolt debuted “The Homely Friendmaker” that the comedic plates shifted. Her name was Phyllis Diller, and her way into the comic scene was to poke fun at herself. “I once wore a peekaboo blouse. People would peek and then they’d boo.” No man needed to insult her; she beat them all to the punch.

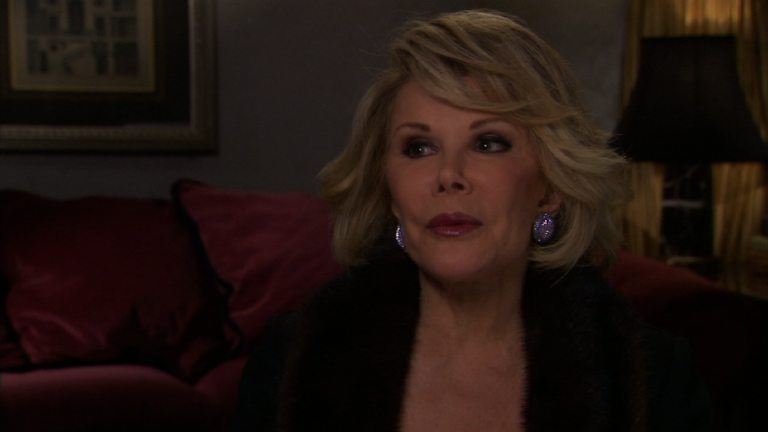

10 years later, Joan Rivers appeared in pearls, a dainty black sheath and a bouffant. But while she looked more refined than Diller, she lobbed as many barbs at herself: “I have no sex appeal. If my husband didn’t toss and turn, we’d never have had the kid.” (She was equally brutal to Elizabeth Taylor: “She’s the only woman to stand in front of a microwave oven and scream, ‘Hurry!'”)

Female comedians have clearly evolved.

As comedian Wendy Liebman pointed out, “Groucho’s lascivious humor towards women, which objectified and belittled us, is evidence of the evolution of equality.”

Today’s female comics are owning their sexuality, chronicling life’s absurdities and commanding center stage. Like Sarah Silverman, who jokes about performing a sexual act and and thinking, “Oh my God—I’m turning into my mother!”

Or Amy Schumer, whose mother is “always saying really smart things . . . like, you probably heard this one, ‘Why buy the cow when the milk has HPV?’ Wish I’d listened to that one.”

Or Chelsea Handler, who notes that women who sleep with men on the first date “probably don’t want to see them again, either.”

Groucho most likely would have attempted to test out that theory. But he also would have appreciated them. As Stoliar notes, he worshipped clever. A dirty laugh, to him, was a cheap laugh.

Up-and-coming female comics credit Groucho Marx with helping their own humor.

Comedian and screenwriter Zarna Garg acknowledges that aspects to his comedy would probably be considered “anti-feminist” and a form of “toxic masculinity.” But she also believes that he would have (perhaps grudgingly) adapted with the times.

“Groucho’s comedy is so foundational to American comedy that you could dig him up and stick him on a stage right now and he’d still be fresh,” said Garg, who came to the U.S. from India at as a teenager.

It’s because of Groucho that she decided to wear a bindi as her signature feature. “For him, it was the eyebrows and the cigar,” she said. “I learned that as a comic having one identifying trait is valuable.”

And the joke always, always came first.

It’s worth nothing that when Groucho won an honorary Oscar in 1974, not long after suffering a stroke, he made sure to thank Margaret Dumont and his mother, Minnie: “Without her we never would have been anything.”

Let us hope that no one ever tries to boycott the boychick. As Gina Barreca, an English professor at the University of Connecticut and author of the best-selling “They Used to Call Me Snow White But I Drifted,” puts it:

“There’s simply an artistry that comes through. Groucho Marx is part of the canon. Everyone’s trying to dismantle it, but if you’re going to know what you’re going to do next, you have to know what comes before you.”