In today’s vernacular, Helen Keller would be called a social justice warrior, but too often people only see her as a seven year-old who learned to communicate at a water pump.

Since her death in 1968, there has been much written about Keller in academic circles, but in popular culture, the play and film “The Miracle Worker,” looms large and tends to freeze the story of Helen Keller as a DeafBlind child struggling to communicate. In fact, she was a prolific writer, world traveler, and advocate for oppressed people everywhere, with teacher Anne Sullivan at her side for 50 of those years. She even had a vaudeville act and starred in a silent film about her life. In the early days of the founding of the NAACP in 1909, Keller, a native of Alabama, was lending her support to African American rights, condemning the unjust treatment, discrimination, and violence that the Black community faced.

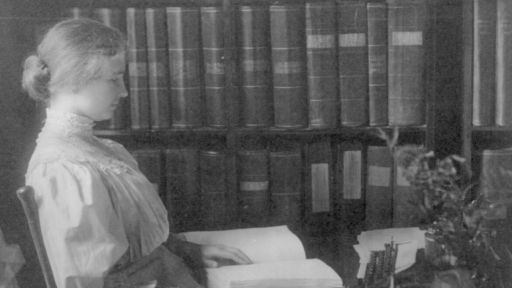

Caption: Helen Keller Radcliffe College graduation, 1904 Credit: The Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (AG Bell)

My personal connection to Keller came in the late 1990s when I was collaborating with a friend who was the research director at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) in New York City. The Helen Keller Archive at AFB was housed physically in paper form at that time, with a traditional card catalogue. As a journalism professor, I quickly focused on card catalogue titles about journalism and magazine writings by Keller. I knew she wrote books, especially the one that would make her a household name, “The Story of My Life” in 1902, when she was still a student at Radcliffe College.

Intrigued by her connection to journalism in the early 20th century, I looked deeper into the Helen Keller Archive and discovered that Keller had a lively freelance writing career for publications as diverse as Good Housekeeping, The New York Times, and The Rotarian and even wrote a monthly column for a women’s magazine in the 1930s. My 2015 book, “Byline of Hope. Collected Newspaper and Magazine Writings of Helen Keller,“ collects and analyzes all her newspaper and magazine articles, as well as her column in Home Magazine from 1930 to 1935. Keller’s magazine column was the most unique find because even her biographer Dorothy Herrmann said she didn’t see it in preparing to write her 1998 book, “Helen Keller. A Life.” I talked to Herrmann on the phone in 2002, and when informed about their topics and the format of the magazine column, Herrmann said she believed those magazine columns in the early 1930s to be some of Keller’s most natural and unaffected writings since she needed little help to create the short one-page columns.

Helen Keller was a woman of diverse interests, but most of all she wanted the world to be a better place for people less fortunate than herself, and those themes can be found in many of her writings. She discussed women’s rights, workers’ rights, disability rights, education equity, world peace, the problem of child labor, and ways to bring social justice to oppressed people. She also knew her audience, who wanted to hear how the famous DeafBlind woman navigated the world, so she also wrote about her sensory experiences with a “world I live in” theme.

Optimism was its own unique theme to both Keller’s life and writings; she even wrote a book called “Optimism (An Essay)“ in 1903.

She was well-known for her positive outlook that combined her iconic status as a disabled person with the hopefulness found in her writings. Her teacher Annie Sullivan attended the Perkins School for the Blind for her own visual impairment, where she learned the communication system for DeafBlind people. In addition to knowing Sullivan’s story of poverty, Keller read widely, and anything that couldn’t be obtained in Braille was read to her. Her own personal successes bolstered her optimism as well. Sullivan saw early on that Keller could be “a symbol of human potential and creativity,” according to Paula Marantz Cohen, who wrote the article, “Helen Keller and the American Myth,” and Sullivan gave her student a belief in herself that she carried into her writing. All of this fed Keller’s core belief system that positive social change could occur.

The monthly column she wrote for Home Magazine in the early 1930s covered all the themes she liked to write about, and her optimistic writing style was the perfect message during the Great Depression. Through Keller’s words, her image, and her iconic status, the Home Magazine column provided a big dose of hope to its readers. The magazine was a unique publishing venture; it was only available in Woolworth stores and advertised products available in Woolworth’s. She produced about 60 columns in a 5-year period. Many of the columns featured Keller’s distinctive signature (she signed in block letters along a straight edge) and a picture of her.

I have always argued that Keller’s writings for these publications, especially during the Great Depression, were valued for the inspirational impact of her byline—a byline of hope—as much as for their content. In the beginning of her magazine columns, Home Magazine explicitly stated (with incorrect facts) that Keller’s role was to provide a positive outlook: “A series of messages to women by a woman who, born blind, deaf, and dumb, is today an undaunted exponent of optimism.”

One of her 1930 Home Magazine columns published less than a year after the 1929 stock market crash has a theme about learning to cope with hardships. She wrote in a column titled “Know Thyself” in February 1930:

“What really counts in life is the quiet meeting of every difficulty with the determination to get out of it all the good there is. I am not advocating a passive resignation to things as they are, but a cheerful resolve to make the best of them.”

It was clear from many of Keller’s columns during the Great Depression that she felt materialistic behavior was immoral and blamed it for the economic crisis. “It has become necessary — or so it seems — to make more and more money at any cost of principles or ideals. Out of this unnatural situation has grown the economic and political dilemmas we are contending with today,” she wrote in 1935 in a column titled, “Our Coming Great Adventure.” She was quite a spiritual person and believed everyone should behave in a fair and ethical way that would uplift their fellow humans, rather than disparage them.

Keller’s columns were a type of public performance of fortitude and optimism in trying times. Home Magazine displayed savvy marketing by having the world’s most famous disabled person appear in the publication monthly, and Helen Keller benefited as well. She “recognized the power of her image. Conforming to it maximized her access to an inhospitable world and monitoring and censoring her own behavior was a constant part of her life,” said Liz Crow in her essay, “Helen Keller: Rethinking the Problematic Icon.” Therefore, the Home Magazine columns gave Keller a way to speak out on her beliefs, while still maintaining her “saintly” image. “The saint was in actuality a spitfire, and her rhetoric was forceful and furious,” according to Susan Fillippeli, who wrote a thesis on Keller’s rhetoric.

Keller also allowed the writings of others to feed her own imagination.

She often acknowledged her debt to other writers for their descriptions and their inspiration to her. In her 1929 autobiography, Midstream My Later Life, she lists many of her favorite authors, calling Walt Whitman her favorite American poet. She said Joseph Conrad was her best-loved author because of his writings about the sea, which she delighted in because of the multitudes for her to smell and touch near an ocean or lake. Following Conrad’s lead, she wrote her own sea tale in a 1934 Home Magazine column about a rowboat ride on a Scottish lake. The column has many visual descriptions that were either relayed to her via sign language or sprang from her imagination.

Keller’s writings have proven extremely quotable over the years. In the 1960s, Hallmark cards began using quotes from her books, poems, magazine articles, and Home Magazine columns. In 2000, the American Foundation for the Blind Press issued a new book of Keller’s quotes, “To Love this Life, Quotations by Helen Keller,” some of which come from the Home Magazine columns. Online, quotes from her writings have become abundant memes, and in 2021, she even had a conspiracy theory associated with her, with young people on TikTok questioning her existence.

Reading audiences could draw inspiration and hope from her writings and her very presence in the world, and I believe her writings of the 20th century can soothe us today. They touch on many of the same issues we face in the 21st century – an unjust and unequal world for many oppressed people, entities that value money over people, and societal barriers that continue to restrict the rights of people with disabilities worldwide.

WORKS CITED:

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Elsa Sjunneson: DeafBlind author [Audio Description + ASL]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2022/03/Rxaa3o7-asset-mezzanine-16x9-JNz2pke-512x288.jpg)

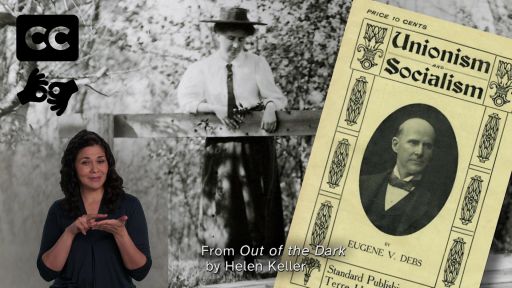

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Helen Keller studied socialism [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/EqPyQ19-asset-mezzanine-16x9-tGsOsJd-512x288.jpg)

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Helen Keller the suffragist [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/yTaS3yJ-asset-mezzanine-16x9-4nbxXU4-512x288.jpg)

![Becoming Helen Keller -- Keller's use of oral communication [Audio Description]](https://pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/files/2021/10/dUfOBIW-asset-mezzanine-16x9-NlZMY6w-512x288.jpg)