American Masters Online presents an interview with “Luce” producer, writer, and director Stephen Stept.

Q: What was the genesis of this project?

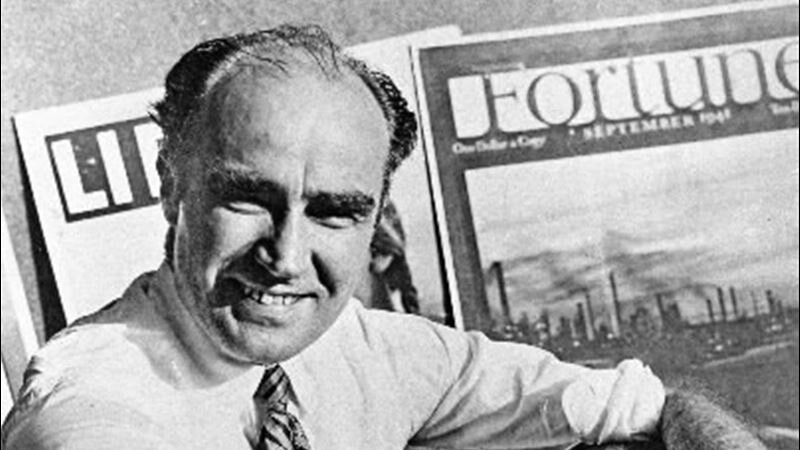

Stephen Stept: The idea of doing an American Masters on Henry Luce came from Susan Lacy, the series creator and executive producer. Susan and I had been talking about doing a project together for a while, and she thought this was an appropriate one for me to do for her. So we embarked on a series of NEH grant applications for script and production that ultimately obtained partial funding to do the show.

I loved working with American Masters. Susan really trusts her filmmakers. While she is ready to jump in with her considerable talent if help is needed, she is also perfectly willing to give you her notes and stand back if things are going well. Happily, things went extremely well on this. We had a terrific working relationship throughout. What is also great about American Masters is its 90-minute format, which really allows you to explore the character and his or her work with a depth that shorter shows often lack. And the shows are all different – no cookie-cutter formula. Susan matches filmmakers with subjects and lets the individual personality of each shine through.

Q: How much did you know about Henry Luce before you started this project?

SS: Not a whole lot, it turns out. I knew that he had founded Time-Life and was a powerful conservative political voice. I grew up in one of those households where my liberal parents cursed Time’s conservative slant, but still read it cover to cover every week. I always turned to the “People” section first, so I thought Time Inc. was really on to something when they started publishing People magazine. Who knew then that they were spawning today’s monster of vicarious journalism?

Q: So what were some of the most surprising discoveries for you?

SS: Oh my, there were so many. I think the first thing was how few people under the age of 40 or even 45 even know who he was. I realized this early on — when I would tell people I was doing a film about Henry Luce I’d usually have to add “the founder of Time and Life magazines” for them to know whom I was talking about. Even the mention of Life magazine would sometimes get a vacant nod. Anyway, as powerful as I may have thought Luce was, I had no idea how commanding a presence he was in the American political conversation throughout the middle of the 20th century. It wasn’t just Time and Life. Millions of people saw The March of Time newsreels in theaters every month. And there was Fortune and Sports Illustrated too. Before television news really came into its own in the 60s, a huge portion of the images people saw, and the way they got their news, fashion and lifestyle was from Henry Luce’s media.

What I also came to understand was not just that he owned and wielded these kinds of media, but to a large degree he invented them. There was no real national news magazine before Time emerged in 1923, and Life, in the way it brought the world into people’s living rooms through its pictures, was as big a revelation as TV would become. Life was as much of a so-called water-cooler phenomenon as TV is today.

Q: What about the man himself?

SS: Fascinating. Complex. Impossible to pigeon hole. As conservative as he was in his day, many of today’s conservatives might consider him downright liberal. He used his platform to shine a light on the racial inequities in this country long before the rest of mainstream media. He was a generous employer who believed benefits were an integral part of compensation. He was a benevolent dictator in that sense, a devout Presbyterian, Republican and super patriot, though he was born in China and didn’t come to live in the U.S. until he was 14 years old.

What I found most captivating was his insatiable curiosity about anything and everything in this world. And his magazines reflected it. His own writing and speeches cover a wide variety of subjects. He thought deeply about so many issues – politics, religion, art, history, economics – and to some degree it all ended up in his magazines. It was Luce who coined, or at least popularized, the term, “The American Century,” in a Life editorial back in 1941, ten months before Pearl Harbor. He had a vision of America’s role in the War and in the post-war world that many Americans continue to embrace today. This was what we were thinking of when we titled the show “A Vision of Empire.” This and his vision for the media empire that he was building.

Luce was a missionary’s son and he brought a sense of mission to journalism – it was a calling, and he approached Time Inc. as both capitalist and missionary. His goal was not only to have the most successful media enterprise, but he took very seriously his responsibility to inform and educate his readers, to raise the level of discourse in this country. Whether he succeeded or not is subject to debate, but there is no denying the depth of his commitment.

Q: Tell us about making the film?

SS: This was a real treat. Imagine spending your research days going through old Life magazines. It’s a dirty job but somebody’s got to do it, right? When you spend enough time with them you understand – through the choices of photos, the juxtaposition of photos, ads and text – Luce’s editorial vision of the world. I really enjoyed the challenge of conveying that in an exciting and vibrant way to our viewers.

And Fortune magazine – oh my God. When I first started doing the research for the NEH proposals [that funded the script and production], I thought that somewhere in there we’d have to do something on Fortune, thinking that as a business mag it would be of limited cinematic interest. And then I finally got my hands on the original issues from the 30s and 40s. You have never seen a magazine like this! Gorgeous cover art, inside pages on thick textured paper, exquisite photos, and brilliant storytelling in a hand sewn binding – an issue today would cost in the neighborhood of $15, and no publisher would dare do it. There is nothing else like it. It tells you a lot about Luce: his insistence on quality, his artistic approach to business and journalism, and his supreme confidence in the capitalist enterprise. The first issue came out two months after the stock market crash of ’29.

Q: What do you want viewers to take away from the film?

SS: As a filmmaker, my goal is to engage viewers, tell a good story, and show them a good time, not unlike Life magazine used to do. As a biographer, I want to convey the complexity and inner workings of this brilliant, infuriating, influential and visionary figure. As 21st century America continues to define its role in the world, his ideas and attitudes still resonate in a striking and meaningful way. I want people to understand, to some degree, its origins. I hope the film will stimulate discussion about what journalism at its best and worst can achieve and convey. It has the power to clarify and to distort in both subtle and blatant ways, all of which is apparent in Luce’s media. But most of all, with all that some might find disagreeable in the way Henry Luce wielded his power, one can’t help but admire his genuine commitment to his craft and to his fellow man.