by JAMES L. BAUGHMAN

by JAMES L. BAUGHMAN

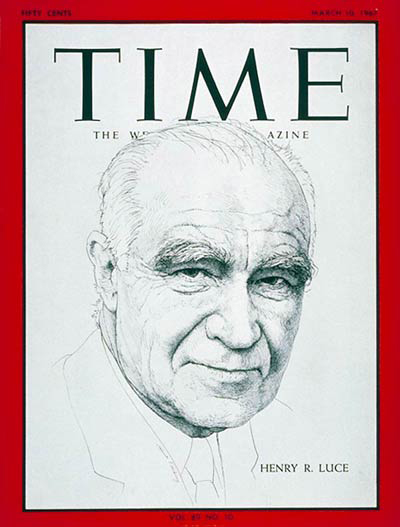

He stood just over six-feet tall, had pale blue eyes and, in his early forties, receding sandy-colored hair, just starting to gray. Although he chain-smoked cigarettes, he rarely drank or ate to excess. Such moderation combined with an overabundance of nervous energy kept him trim. Aside from a habitual seriousness of expression, his most distinctive features were bushy eyebrows. If not so overwhelming as those of such famous contemporaries as labor leader John L. Lewis and Attorney General Frank Murphy, the beetle brows were the physical characteristics that those meeting him for the first time invariably noticed immediately. Newcomers might note, too, odd speech patterns, such as speaking too quickly, his mind racing ahead of his words, or sometimes, a stammer, due to a boyhood speech defect.

In the late 1930’s, he was America’s single most powerful and innovative mass communicator. During the preceding decade and a half, with several other young men fresh from the nation’s Ivy League colleges, Henry Robinson Luce had started distinctive and popular magazines. Taken together these publications provided a more gripping and coherent view of the world than was to be found in similar periodicals and daily newspapers. They had also transformed Luce’s company, Time Inc., into a substantial concern. Luce and his partner had raised eighty-six thousand dollars to start their first magazine, Time, in 1923. In 1941, the revenues from Time, and other Luce enterprises reached forty-five million. (1)

Although up to one out of every five Americans might look at a Luce periodical during a given week, his magazines in 1940 commanded greatest favor among journalists and the middle class. More correspondents in Washington read Time than any other magazine; there and elsewhere many admired and modeled their own work after Time’s peculiar and omniscient mode of news writing. It commanded an audience well outside the federal city. Younger, better-educated members of the middle class had begun to consider Time required reading. Their wealthier neighbors not only took Time, but Fortune, Luce’s lavishly illustrated business monthly.

The most read of any Luce publication in 1940 was his latest creation, Life. Published weekly, Life introduced its readers to photojournalism. Life used pictures to accomplish what Time labored to achieve with words: offer a compelling summary of the week. In barber shops and beauty parlors, on trains and in two million homes, Americans thumbed through the glossy-paged picture magazine. Pollster George Gallup discovered, according to one Time correspondent, “that the biggest publicity break a movie can get is a two-page layout of stills in Life,” – better, indeed, “than a page-one news break in all U.S. newspapers.” (2)

More and more Luce found acknowledgements of his rank as a minister of information. At his Hyde Park home President Roosevelt was sufficiently annoyed by Time’s coverage of election night 1940 to demand a correction. The writer’s details were all wrong, the president complained, and yet the story had been written in the “know-how” style characteristic of Time that persuaded the reader of its veracity (3). A year later, Luce loomed in a screen biography based on one of Luce’s failing rivals, newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst. Only two decades earlier, as Luce and Briton Hadden began planning Time, Hearst published newspapers in virtually every major American city. He was widely regarded as the nation’s most powerful and dangerous publisher. Citizen Kane, however, showed Hearst’s empire in decline and a new one emerging: Time Inc. “With the breaking up of the old personal newspaper empires,” Business Week reported later, “Henry Robinson Luce comes as close to being Lord of the Press as America can now produce.” (4)

The Missionary, 1940-1967

Had Luce died in 1940 he would have been remembered for his inventions. Instead, he lived another thirty-seven years and came to be hated, even after his death, for his prejudices. Until the late 1930s, Luce’s publications could convey contradictory points of view. Liberals and radicals at Fortune and Time swiped at capitalism and imperialism; one foreign affairs editor at Time could not disguise an infatuation with fascism. More frequently, Luce’s magazines seemed merely smug. All of this started to change as Luce himself turned his attentions more toward public affairs. It was perhaps inevitable. Born in China, the son of an American missionary educator, Luce regarded journalism as a “calling,” a positive, educative force. Then, too, his father’s career had symbolized to his son America’s potential for good works. The son’s material success reaffirmed a boyhood appreciation for capitalism. Starting in 1940, Time Inc. publications at times deliberately presented the news in ways that revealed Luce’s preoccupations. The magazines continued to summarize events in typical Time fashion, but after 1939 they regularly ridiculed opponents of certain policies Luce advocated. The intellectually dishonest or simply mediocre champions of Luce’s causes more likely obtained good coverage. Years of editorial cleverness were now being used to promote the foreign policies of Henry Luce. “No restraint bound him,” recalled one of his correspondents, “in using his magazines to spread the message of his conscience.” (5)

Luce’s concern for the world began with the Second World War. Like many members of the Eastern Establishment – an informal collection of publishers and political and financial leaders – Luce viewed the early victories of Nazi Germany with alarm. No longer, Luce argued, could America afford her traditional isolation from the world. Even if Britain stopped Hitler, Luce correctly surmised, the war would leave her too exhausted to play the great world power. Americans had to be made to accept the “inevitable”: armed intervention to save Europe and a new postwar order dominated by the United States – Luce called it the American Century.

Luce’s vision of America hegemony still faced obstacles. Some powerful conservative elements within the Republican party and some newspapers, most notably the Chicago Tribune, fiercely opposed Luce’s new imperialism. Abroad, the Soviet Union began late in the war to assert its own will over Eastern Europe. Even before the disintegration of the U.S.-Soviet alliance. Luce’s magazines, in 1944 and 1945, started to question Russia’s intentions for the postwar world. Stalin, like Hitler, seemed bent on upsetting a balance of power favorable to the United States.

Once again Luce’s magazine framed news stories to leave little doubt that America must face up to this new aggressor. In the 1950s, Time Inc. publications fostered a consensus enveloping and deadening discussions of American foreign policy. Critics of America’s containment of the Soviet Union – on the left and right – were brutally handled, and every confrontation with the Communist world and even the neutral block celebrated. Luce himself told a Senate committee in June 1960, “I do not think there can be a peaceful co-existence between the Communist empire and the free world.” (6)

The Costs of Commitment

Luce’s magazines had been attacked sine the 1930s. Time’s initially unusual style pained some critics; Life appeared to make too many compromises to achieve greater circulations. In the 1950s and 1960s, such criticisms increased; both periodicals were accused of cultivating “middlebrow” cultural tastes and Time, of highly prejudiced political reporting, presented as objective synthesis. Time, remarked one former editor, “is the most successful liar of our time.” (7)

Nevertheless, it was Luce’s close association with a vigorously anti-communist foreign policy that cost his reputation dearly. Luce became, wrote Joseph Epstein, “a great grey eminence whom everyone, with tar brush in hand, painted black.” (8) No other publisher of his rank had offered, in his own words, such resolute calls for American hegemony. And to those in the late 1960s outraged over the cost of that globalism in Vietnam, Luce and his magazines bore much of the responsibility. “The Lucepress had led, not followed, the nation into war,” biographer W.A. Swanberg wrote. Luce stood guilty of “manipulating 50 million people weekly.” (9)

Such appraisals can be misleading. Most Americans did not regularly read a Luce magazine; in a given week, far more were likely to scan a daily newspaper and listen to a radio newscast than to examine an issue of Life. Nor did every subscriber absorb whole the arguments in all the articles in each issue. Luce’s publications alone did not frame or structure readers’ view of the world; for many, they served as supplements to friends and neighbors, newspapers, and broadcast news services. These other voices, in turn, often echoed Luce. By the late 1940s, virtually all the popular press shared his hostility toward the Soviet Union. But not all advocated what came to be Luce’s moralistic approach to foreign policy. Nor were Harry’s ardent views on China found in every national and local news service. Nevertheless, rival mass communicators had come to accept the fundamental premises of the American Century.

Then, too, Luce’s role was most often limited to that of a publicist, not an initiator, of policies. When the Roosevelt administration refused to place him on a special commission reviewing postwar economic policy, he could only publish, as opposed to participate in, its determinations. Later in the decade, his lobbying for China, under siege from Communist insurgents, went largely unheeded until it served the political needs of Republicans in Congress; they and Luce then watched helplessly as the United States abandoned any attempt to save China from the Communists. In the 1950s and 1960s, Luce received more attention from both Republican and Democratic presidents. Yet they approached him after making decisions, not before. Luce served as an information minister, not foreign secretary.

The Press Revolutionary

To note the limits of Luce’s power and the representative nature of his opinions is not to diminish the importance of his journalism. His most severe critics would blame him for what he argued. Too conveniently of self-servingly they ignore how many not on Luce’s payroll shared his basic assumptions about the Cold War. It is not, then, so much what information he conveyed as how he did it. Time and Life, and to a lesser extent Fortune and “The March of Time,” helped to change the practices of American journalism. Luce and his collaborators deliberately sought to create new ways of relaying the news. And by succeeding, Luce helped to alter the profession forever.

Luce’s formula involved little more than cleverly summarizing the week’s news in print (Time) or pictures (Life) in ways that left the readers with a concise, entertaining, and frequently inadequate version of an event or trend. Complex “running” stories were simplified. Normally, the Time entry emphasized “personality.” Time, in fact, invented the newsmagazine “cover story,” usually on an individual as metaphor for what was or should be happening. “Knowing,” if irrelevant, details flavored an entry. Above all, Time, Life and Fortune stories possessed “omniscience,” an all-knowing point-of-view. Often Luce’s journalism offered little but the illusion of information. Readers, knowingly or not, surrendered to Time writers the right to sift through facts. Some subscribers wanted Time and other Luce publications to “mediate” information for them. Working in business increasingly dependent on national and international events, they sought a succinct or “efficient” view of the world. Other readers experienced a crisis over information ineffective newspaper subscribers, ones whose inability to absorb the news left them with a fear of inadequacy. The whole realm of knowledge, of government, technology and business, had expanded and complicated life. Although more Americans had gone to college than ever before, most institutions of higher education at the turn of the century had begun to abandon the idea that the whole of human endeavor could be understood. An increasing number of college students, like Luce and his classmates at Yale, had begun to “concentrate” in certain fields. Work itself became more focused, with people accordingly less aware of more things. To this ignorance, Luce and his partner, Briton Hadden, consciously played. Time would summarize and explain trends not only in politics and diplomacy, but in the arts and sciences, clearly, cleverly, knowingly. Analyzing a 1934 radio program that assessed literature and the theatre, historian Joan Shelley Rubin saw Swift’s Premium Hour fulfilling a similar function. The programs “did not pretend to provide literary analysis or to teach the audience to arrive at its own critical judgements. Their function was instead to create in the listener the sense that she or he was ‘in the know’ about the arts.” (10) The Olympian Time writer would similarly determine what a weekly news item “meant.” “The dream,” a former Time writer observed, “was that an external truth exists this week and can be expressed in 500 words by a talented writer after he had read the week’s New York newspaper clippings.” (11)

In time, Luce’s formula of the directed synthesis could be seen in competing news services: in radio and television news reports, in an increasing number of newspaper columns and analyses. His legacy thus concerns a transformation of American journalism form information to synthesis, and another episode of what Raymond Williams has called “the long revolution,” the centuries-long struggle, first through literacy, to gain access to the printed word, and then , through new mass media, to achieve a mastery of a more complicated order. The most successful mass media managers devised forms that rendered a more complex and crowded world comprehensible. By succeeding, the mass communicator created a harmony, whereas individual experience or physical isolation might only have fostered faction or worse – to the purposeful Luce – disengagement. (12)

Because Luce’s publication sought to create and control a national consensus, he chose his causes more carefully than some detractors have admitted. Most of the time he looked to others within the establishment or government, or to commentators like Walter Lippmann, before committing his publications. Deeply ambitious, he hated to lose. “He could, and often did, mount sustained campaigns,” wrote William F. Buckley, Jr., “but the goals were carefully chosen, and above all they were realizable. Luce had an aversion to lost causes.” (13)

Luce’s career, then, took two stages. The first and more vital involved the evolution of new types of information media, the news magazine, the thoughtful business periodical, the photoweekly. By the very late, 1930s, these inventions had become innovations, popular and profitable. At this point, the publisher began to assume an interest in public affairs. Although still a publisher, never a politician, Luce became a “public man,” more concerned about presidential politics, world affairs, and the quality of life of the American middle class. For him, this second act was more frustrating. Not until his last years did he overcome a restlessness about his works, his country, even his personal life. Yet he never lost the confidence he had as a young man that his journalism could inform millions and hold the modern state together.

Footnotes:

1 Robert T. Elson, The World of Time Inc., 2 vols. (New York: Atheneum, 1968-73), 1:447-48.

2 W. Rich to Frank Norris, 5 July 1940. Daniel Longwell Papers, Box 29, Columbia University, New York City.

3 Roosevelt to Luce, 20 November 1940, Roosevelt Papers, President’s Personal File, Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York.

4 Business Week, 6 March 1948, 6; PaulineKael, “Raising Kane,” New Yorker, 27 February 1971, 49-50, 52, 57.

5 Theodore H. White, In Search of History (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), 126.

6 U.S., Congress, Senate, Government Operations Committee, Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery, Organizing for National Security, Hearings, 86th Cong. 2d sess., 1960, 923.

7 Ralph Ingersoll, quoted in “Time: The Weekly Fiction Magazine,” Fact 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1964): 3.

8 Joseph Epstein, Ambition: The Secret Passion (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), 147. Compare with Epstein, “Henry Luce and His Time,” Commentary, November 1967, 35-47.

9 W.A. Swanberg, Luce and His Empire (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972), 472.

10 Joan Shelley Rubin, “Swift’s Premium Ham: Wiliam Lyon Phelps and Redefinition of Culture,” in Mass Media between the Wars: Perceptions of Cultural Tensions, 1918-1940, ed. Catherine L. Covert and John D. Stevens (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1984), 12.

11 David Cort, “Once Upon a Time Inc.,” Nation, 18 February 1956, 134.

12 Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution (London: Chatto and Windus, 1961); James W. Carey, “The Communications Revolution and Professional Communicator,” Sociological Review Monographs, no. 13 (January 1969), 23-25.

13 William F. Buckley, Jr., The Jewler’s Eye (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968), 340-43.

This essay was adapted from the book “Henry R. Luce and the Rise of the American News Media” by James L. Baughman.