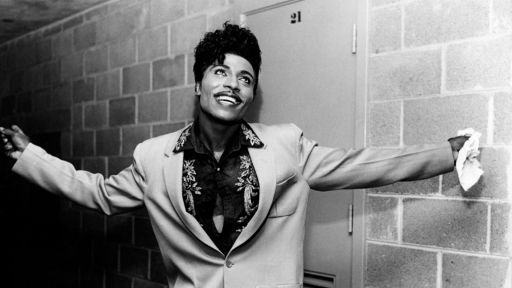

by Mikal Gilmore

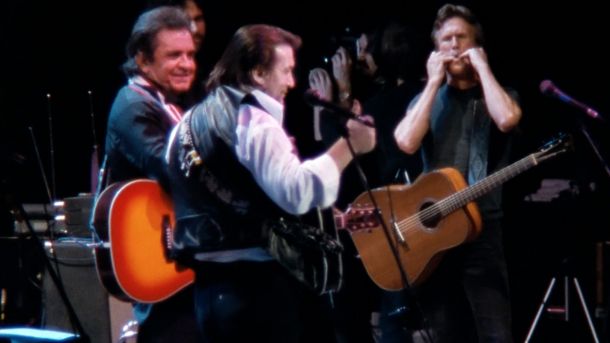

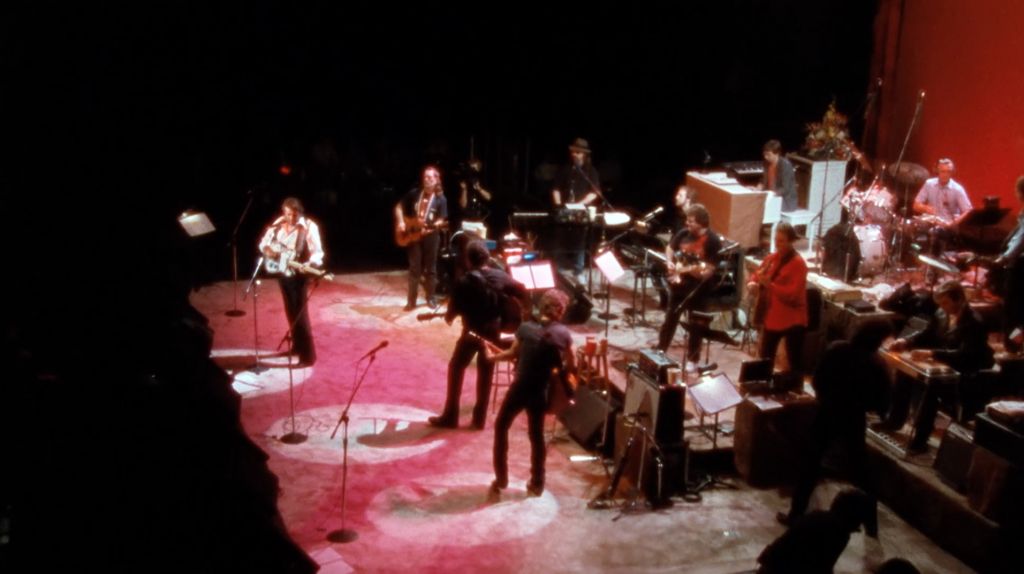

The Highwaymen performing at Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., in 1990. Screenshot from The Highwaymen: Friends Till The End. Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

There is a moment around midway through this set’s Nassau concert that focuses the group’s fellowship: Kristofferson, Cash, Jennings and Nelson take turns at Kristofferson’s “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33.” The song is similar to “Sunday Morning Coming Down” — another look at a man who is “Never knowin’ if believin’ is a blessin’ or a curse/Or if the goin’ up was worth the comin’ down…./Runnin’ from his devils, Lord, reachin’ for the stars/And losin’ all he’s loved along the way.” The man is a poet, he’s broken, he passes out on sidewalks, yet his waywardness is essential to the truths he’s searching for—truths that, ultimately, might serve somebody else’s life better than his own, if he can only get his words sober and voice right. It’s a beautiful and heartbreaking performance, and at its end Kristofferson points at each of the other singers and smiles, in a moment of loving friendship and faith. There are several such stories and gestures of fraternity during the concert, including “Desperados Waiting For A Train” — one man’s elegy to a dying friend—and “The Last Cowboy Song,” a requiem for “another piece of America’s lost.” There’s also the heartening looks the singers give one another, the roughhewn grain of their solo and harmony vocals—all testaments to the pleasure and purpose found by standing on a stage together, taking part in having deepened American musical tradition with their indomitable vision and determination. “This night, on the Nassau show,” says Jessi Colter, Jennings’ wife and frequent singing partner. “They were really on it. They were always on it, don’t get me wrong—but that one…fantastic. Maybe it had to do with the moon, the night, the sound system, everybody’s energy,” says Lou Robin, “Johnny was suffering from immense jaw pain throughout the night — he could only be filmed from one side of his face. But everybody knew this would be the show to film. We knew there would be a big crowd, and the guys had now played together for a while.” Willie Nelson agreed. “We wanted to work it out,” he said. “I think it’s one of the best things that’s ever really happened to me, to be able to work with these guys, because these are not only friends of mine; these are heroes. Every day is just wonderful on this tour. Even the bad things that we won’t talk about.”

When you watch backstage interviews with the band members, or their conversations from a later documentary, Live Forever, Kris Kristofferson seemed invariably to be of modest temperament. “That was always very humbling to me,” he said recently, “to look down the stage and see John and Waylon and Willie. To be up there with them — you know, it was one of the wonders of my life. These guys were my heroes.” Still, Kristofferson was as formidable as any of the other Highwaymen. Cash, Jennings and Nelson championed and recorded his songs in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when several others on Nashville’s Music Row regarded him with suspicion, even hostility. “When I first heard ‘Bobby McGee,’” Willie Nelson says in an interview here, “I thought, Well, why didn’t I write that? It had all the ingredients of the things I like to see or hear in a song, from all about freedom and traveling, even down to the red bandana, so naturally I related to that song a lot…. Kris must’ve lived a thousand other times in a thousand other places, because he seems to be able to describe all these stories so vividly. That makes him one of the greatest writers of our time.” On another occasion, Nelson said, “Kris gave us a deeper look into the human being, and that added respectability to country music.”

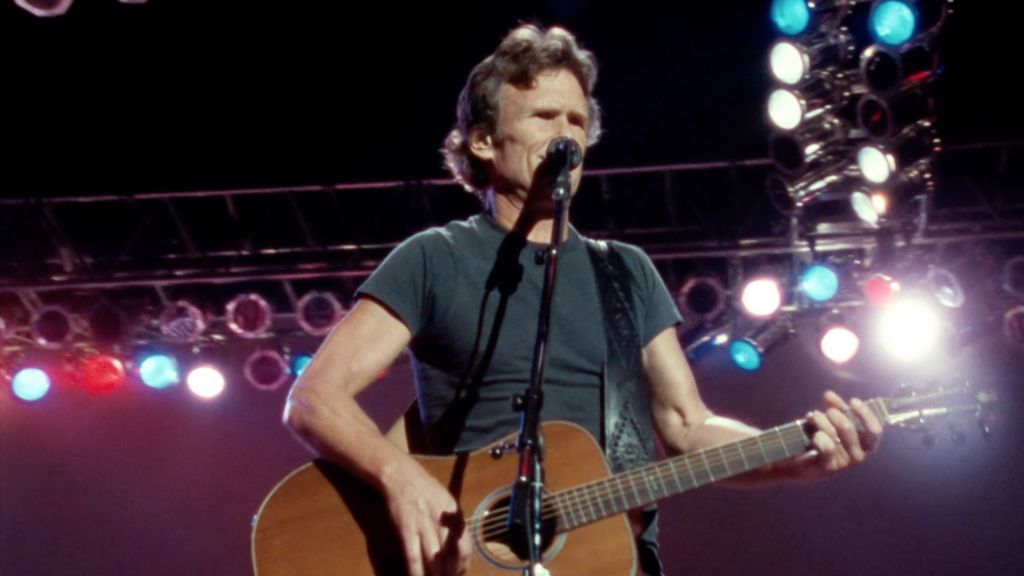

Kris Kristofferson performing at Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., in 1990 with The Highwaymen. Screenshot from The Highwaymen: Friends Till The End. Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

But Kristofferson’s humility didn’t make him reticent when it came to some matters, and the respect of his friends didn’t spare him of their tempers. “We all have our idiosyncrasies,” Johnny Cash said in the documentary Live Forever. “We never had an argument over religion or our faiths. If we’re treading on strange ground we don’t say anything about it. Politics,” Cash added with a laugh, “is another thing. I like to see Waylon and Kris talk about politics.”

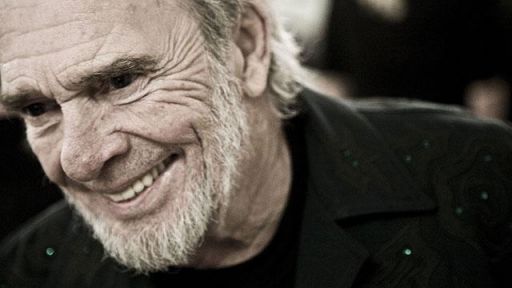

Johnny Cash performing at Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., in 1990. Screenshot from The Highwaymen: Friends Till The End. Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

Cash recalled an occasion when Kristofferson was performing “Slouching Toward The Millennium”: “Kris started making a speech about how many babies have we killed in Iraq with the bombing? And we’ve destroyed the infrastructure of the country. I didn’t know it at the time but Waylon said General Colin Powell was down in front, just standing there, listening to Kris. I guess Kris knew he was there, but I didn’t until we came off, and Waylon said something to Kris. That really started it. We’re not talking about coming to blows, but we’re talking about keeping the blood flowing.” Jennings later said, “We came pretty close to punching it out. I didn’t say he was all wrong. Main thing I was saying was he shouldn’t have been doing it onstage with three other people on there who didn’t share all of his thoughts.” Mickey Raphael, Willie Nelson’s longtime harmonica player, was present for the incident. “Kris Kristofferson was the rebel,” he says. “Some of his songs were almost protest songs, about Sandinistas, about migrant workers. He was saying, ‘Look at our faults, we can do better.’ Kris would get a little too far left, Waylon would want to reel him back in. ‘You can’t say that to our fans.’ Willie, meantime, would say anything he could to get them all crazy, to stir fire. All opposites. Johnny was a father figure to Kris, but they were polar opposites—alike, but different sides of the spectrum, Johnny Cash, with a picture of Nixon; Kris Kristofferson, Che Guevara. The four covered the hemisphere politically. Sometimes there was tension. Maybe Kris said something, pissed off Waylon. They’d get each other’s goat, mess with each other as brothers would. But from the outside they would band together. ‘Me against my brother, all against the infidel.’”

“It wasn’t so amazing that Kris said that with Colin Powell in the audience,” says Annie D’Angelo Nelson. “It’s the fact that the Highwaymen were so diverse, they touched so many people’s lives, that Colin Powell was in the audience. The bottom line was, all these guys believed in peace, but maybe some of them had different ideas about how to attain it.”

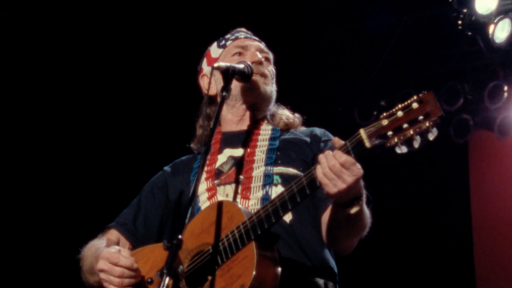

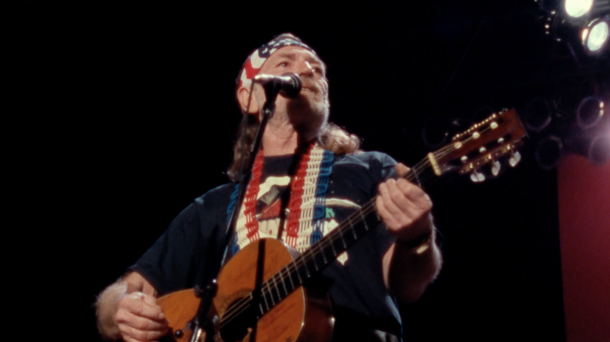

Willie Nelson performing at Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., in 1990 with The Highwaymen. Screenshot from The Highwaymen: Friends Till The End. Courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment.

Indeed, the Highwaymen were big enough to contain America’s truths as well as its arguments. One night Kristofferson sang “Johnny Lobo,” about native American activist John Trudell who had served in Vietnam but felt so dishonored back home that he burned an American flag on the steps of the FBI building in Washington, D.C. Right after “Johnny Lobo,” Johnny Cash—introducing his song “Ragged Old Flag”—told the same audience, “I thank God for all the freedoms we’ve got in this country. I cherish them and I treasure them—even the rights to burn the flag. I’m proud of those rights. But I tell you what, we’ve also got…” He paused, because the crowd had started booing loudly enough to drown him out, then he confidently hushed them. “Let me tell you something — shhh — we also got the right to bear arms, and if you burn my flag, I’ll shoot you. But I’ll shoot you with a lot of love, like a good American.” It was a statement full of extraordinary twists and turns, genuine pride and dark-humored irony—and only Cash could get away with weaving such disparate stances and affectionate sarcasm together. When all was said and done, Johnny Cash looked at America the same way he looked at himself: with forthright regrets and unrelenting hope.

One night backstage, Cash overheard Kristofferson’s young son tell another child, “I’ll shoot you.” When Cash learned that the boy had picked up the phrase from Cash’s own speech on stage, Johnny said, “That’s wrong. “I’ll never do that again.” And he never did.