TRANSCRIPT

♪♪ [ Wind blowing ] [ Haunting music playing ] ♪♪ -He is one of the greatest of American 20th-century artists.

He is absolutely of his time and of his generation.

-In the ways in which he shows figures alone, figures interacting with others, Hopper's art mirrors his life from beginning to end.

-One can look at these pictures and take from them meanings and stories and feelings and impressions that are, in some ways, endless.

-Hopper was aware of, and responding to, a kind of isolation.

What happens when one is alone?

That can be psychological, that can be physical, that can be social.

And I think that was definitely part of the human condition that he wanted to articulate.

-He was solitary.

He wouldn't speak to her for, in some cases, days on end when he was working.

It was a volatile marriage.

-It's hard for the layman to understand what the painter is trying to do.

The painter himself is the only one that can know, really.

If I don't have something to say, I don't try to say it.

♪♪ ♪♪ [ Soft piano music playing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Birds chirping ] Nyack, which is 30 miles north of New York City, was a shipping, working town, and Edward Hopper's family was among a merchant class.

They had family money that helped to sustain them in hard times.

The outside came in through books, but it also came in through periodicals and magazines that they received.

That was part of the fabric of this house.

So, it was an open family.

It was open to new ideas.

I think this is a room that probably shaped him and had a formative influence on his interpretation of light, of windows, of space, of interior and exterior and the views directly to the river.

Edward Hopper loved to sail.

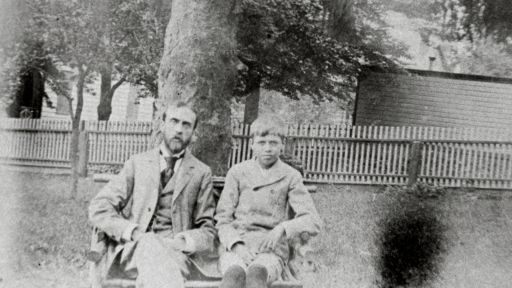

There's a beautiful photograph of him as a young child, maybe 7 or 8, in a rowboat.

Here he sits alone but content on the water.

His mother knew how to encourage him to draw.

He was curious and was given notepads to walk the town to capture the people's expressions.

I think he just was allowed to be creative and that was something that really set his family apart, rather than pushing him to business, pushing him to a profession.

-The major impact his father had on his life was clearly the love of reading.

He was described as bookish.

He said, "My father should have been a poet or a philosopher."

The other major factor was a growth spurt.

By all accounts, he grew approximately an entire foot in eighth grade.

So, at one point, he was 6'4" as an adolescent, and that had a great impact.

There were descriptions of him having painful discomfort as a result of this growth spurt, but also his self-image suffered.

He was taunted by children at school.

They bullied him.

-Edward Hopper was in high school and working as the artist of his high school newspaper.

He realized there was a role that an artist could play.

There are people that are just born to be what they're going to be.

And I think he is a rare example of someone that was born to be an artist.

He intrinsically had the talent and had the drive and the proximity to New York really allowed families to be exposed to more culture.

So, the Hoppers were known to go into New York to cultural events.

And I think that exposure enabled Edward Hopper as a youth to consider going into art school, going into New York, as he knew that that was the center that he needed to be to become the artist that he wanted to.

♪♪ ♪♪ -I've always been interested in approaching a big city in a train.

There is a certain fear and anxiety and a great visual interest in the things that one sees coming into a great city.

-At the moment that Hopper is moving through art school, he is studying in New York, he's studying under William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri.

And even that, in and of itself, signals how art is shifting and responding to European influences.

Hopper began his career as an illustrator, and he knew how to record that which was in front of him, but he wasn't interested in recording the American experience at this time.

He's not invested in that, at all.

-I think that the confines on his creativity as an illustrator is what challenged him, which made him fight, because I think he wanted to create on his own.

He wanted to say, "This is my work."

[ Ship horn blowing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Horse neighs ] -I do not believe there is another city on Earth so beautiful as Paris nor another people with such an appreciation of the beautiful as the French.

-Young artists were all going off to Paris, and most of them wrote about living the bohemian lifestyle, staying in boarding houses, cafes, spending time, perhaps, with women of ill repute.

Hopper went to Paris with his parents' permission.

They supported him, but only if he dwelled in a church mission.

-The artists we think of as the artists of Paris, at that time, were Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani, all congregated up the hillside in Montmartre, and that was not Hopper's patch.

-Other young artists in Paris are out sowing their wild oats, so to speak.

Whereas in Ed's case, under the matriarchal thumb of his mom, is off in Paris literally living with the church ladies.

And so that certainly would have impacted how he interacted with women.

The romance that Hopper pursued with Alta Hilsdale, largely in Paris, spanned 1904 to 1914.

We did not know about her presence in his life until the letters recently emerged from the attic of the house here in Nyack.

And on all three occasions that he traveled to Paris between 1906 and 1910, I believe, she was there.

It is very clear that the relationship at best was dismissive.

So that really describes pretty much the whole tenor of the relationship.

-"My dear Mr. Hopper, I am very sorry you were so bored, and also that I cannot possibly see you until Thursday."

"I cannot go out to dinner with you tonight.

I'm very sorry, but I have another engagement."

"My dear friend, I do wish you wouldn't take everything so alarmingly seriously.

I don't think you at all reasonable.

You are the type of a man who does not believe a girl can be platonic indefinitely."

"My dear Mr. Hopper, I am to be married soon.

I cannot tell you how sorry I am to have made you unhappy."

-How overwrought and crestfallen and devastated Hopper was upon the news that Alta was, in fact, marrying this other man.

Apparently, he tried to go see her and she said no, and there was this sort of heated exchange back and forth.

It's pretty clear that there were romantic, perhaps sexual, overtures that were not welcomed.

So basically, the whole tone of the relationship for 10 years is him pursuing her and her sort of putting him off.

-One of the most enigmatic paintings he ever painted is called "Summer Interior," which shows a partially clad woman; she's naked from the waist down, slumped on the floor.

She clearly is the victim of a sexual trauma of some kind.

It was painted right after he returned from Paris after his most recent heated exchange with Alta.

You can no longer look at that painting and divorce it from the context of everything we know about what's going on in his emotional life at the time.

In fact, another scholar said she's sure that that ashamed, embarrassed, traumatized, victimized, sexually distressed figure on the floor is him.

It is deeply uncomfortable.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -3 Washington Square North was kind of a famous building within the artistic community.

It had been really turned into a studio building, a number of artists before him, writers before him, a center of cultural activity.

It really was one of the most New York of places, in many ways, a perfect spot for an artist.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -His tour-de-force painting at that time is the painting "Soir Bleu," which is a painting that, for him, he painted in 1914, which was about four years after he returned from his last trip to Europe.

-So, basically "Soir Bleu" is an outdoor-cafe scene, and it's a place that he actually went with Alta.

We see a figure of a clown painted in white.

We know that that's Edward Hopper.

We have a prostitute who is there procuring business.

It appears as if her pimp is sitting at the table across from the clown figure.

So, he's basically gone back to a place that he went with Alta and played this scene of despondency, sexual distress or sexual misbehavior.

So, the word that's often used to describe it is cynicism.

-This was a painting that, in many ways, kind of synthesized his own admiration for Degas, early Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec.

The "Soir Bleu" was castigated for being a very French-looking painting.

He was highly criticized for it.

And, basically, he rolled it up, and it was never shown again until the Whitney unrolled it.

♪♪ -In every artist's development, the germ of the later work is always found in the earlier.

The nucleus around which the artist's intellect builds his work is himself, the central ego, personality, or whatever it may be called.

This changes little from birth to death.

What he was once, he always is, with slight modifications.

♪♪ [ Waves crashing ] [ Melancholy music playing ] ♪♪ ♪♪ -Edward Hopper first comes to Gloucester in 1912.

At that time, he's still making his way.

He hasn't even sold his first painting.

When he returns in 1923, he meets Jo Nivison.

We know they were attracted to one another, and they both remember the moment where Edward Hopper began reciting, quite slowly, poetry by Paul Verlaine, his favorite symbolists, and without missing a beat, Jo picked up where he left off and recited the poem in French.

So that was where they cite the beginning of their understanding that they were more than painting partners.

They were gonna become life partners.

-In 1923, Hopper had not sold a painting in 10 years.

In the Armory Show in 1913, he sold an oil called "Sailing."

But in the ensuing 10 years, he had exhibited work and had no sales.

Jo, at the same time during that period was probably at her most productive.

She was showing her work in numerous exhibitions, with the other modern painters of the day and also selling her work.

-She recommended him to gallerists and got him some interest in his work, from which point on, his career soared and hers sort of seemed to collapse.

-At Gloucester, when everyone else would be painting ships and the waterfront, I'd just go around looking at houses.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Mansard Roof is a house that still stands today on Rocky Neck in Gloucester Harbor.

But it seems to me the most joyous that we think of Edward Hopper ever.

And when it is shown at the Brooklyn Museum exhibition, that becomes the first sale of any work Edward Hopper has had since 1913, so in a decade.

And they pay $100 for it to enter the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

And it's on that basis, Jo's advocacy, her painting side-by-side with him in Gloucester, that then he's off and running on his career.

So, they come back to Gloucester and, after some great heated debate, Jo convinces that she's not coming back unless they're married, and they do come back as a married couple in 1924.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -It becomes clear that they painted side-by-side.

This is a husband-and-wife painting team.

And, again, they have chosen the identical locale and they're sitting next to each other.

So, the compositions are identical.

-It's clear that his style changes under the influence of Jo, specifically his palette.

Jo's colors are much more spontaneous, much more expressive, and so he starts to take on those same qualities in his palette.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Hopper's New York is so silent, it's almost eerie, but it's almost welcoming in that it's another vision of Manhattan.

We don't have the cacophony of the subway, of the voices, of the peddlers on the street.

We don't have the crush of bodies.

We have an artist who is stripping out his canvasses, imagining a city that is very much of his own creation, not doing anything any New Yorker or other artist is really doing at this time.

-Well, I like buildings and I like people... somewhat.

I like landscape, somewhat.

They all go together in my mind.

I'm a painter of rather wide range of subject, really, if you know my work.

Perhaps more than any painter I know.

I've done an awful lot of different kind of things.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -You have to remember he is coming to maturity at the time that the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building are built.

You would think every building in New York City was no more than three or four stories.

That is pretty extraordinary.

So, he is trying to escape the city as much as he is trying to preserve the city.

-I think Hopper was aware of, and responding to, a kind of isolation.

What happens when one is alone?

That can be psychological, that can be physical, that can be social.

And I think that was definitely part of the human condition that he wanted to articulate.

♪♪ ♪♪ -He had the just uncanny ability to paint pictures that have a lot of details that don't quite add up.

We know it's an automat because that's the title of the picture.

But we don't see any of the little doors with the pieces of pie behind them.

We don't see any other people, even though they were incredibly popular restaurants in Hopper's day.

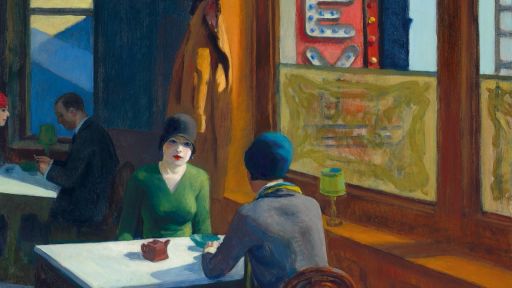

♪♪ ♪♪ If you look at his pictures, the values of contemporary society are reflected in them.

One of my favorite Hoppers is a painting called "Chop Suey," and it's two women sitting.

It must be at lunchtime because there's a lot of sun outside.

They're in a Chinese restaurant.

And extraordinarily, they are out on their own without male escort.

They are dressed up and they have a lot of make-up on, which in an earlier generation, might have indicated that they were available.

In fact, what Hopper's commenting on is a social change that had been coming for a while but that had affected women of his generation who were more independent.

So those kinds of quieter social comments are in his work.

♪♪ -I spend many days usually before I find a subject that I like well enough to do and spend a long time on the proportions of the canvas, so that it will do for the design as nearly as possible what I wish it to do.

♪♪ I am fond of "Early Sunday Morning," but it wasn't necessarily Sunday.

That word was tacked on by someone else.

-"Early Sunday Morning," of course, 1930, not only being a year where the city was absolutely in this kind of devastating moment, the Great Depression, but also, in this total New York way, the Empire State Building was being built, the Chrysler Building was being built.

The city is both, at this moment, in financial despair and still soaring higher than anywhere else in the world.

And you see the much-talked-about dark, kind of looming rectangle in the top right corner that would signify a building being built, some kind of hovering presence around it.

So, I feel like, in many ways, this painting kind of captures all of what's going on in the city at that particular moment.

-The world kept changing.

The world kept moving.

Yet his vision was apart from the world.

You never see crowds of people.

You never actually see more than usually a few people in a room at any given time, maximum.

You never see people of color.

On one hand, it's totally of its time.

And, on the other hand, it ignores other things of its time.

I think it's in those contradictions that are its strength but also it makes you see that he was in a bubble of his own.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -The idea for "Room in New York" had been in my mind a long time before I painted it.

It was suggested by glimpses of lighted interiors seen as I walked along the city streets at night, probably near the district where I live, although it's no particular street or house, but rather a synthesis of many impressions.

More of me comes out when I improvise.

♪♪ -His relationship with Jo was very, very fraught.

He was a very aggressive person in his quietness.

He overshadowed Jo in many ways.

And the kind of classic notion of the wife supporting the husband, that was clearly the case.

She was a serious artist in her own right.

It was also a very jealous relationship.

She didn't allow Edward to paint from any other model except herself.

-And so having her pose for him was easier than him having to go and procure the services of someone else.

So, depending on what he needed a woman to do or what role he wanted a woman to play, Jo was conveniently present.

♪♪ -Sometimes talking to Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well, except that it doesn't thump when it hits bottom.

Everything must work according to his personal reactions, prejudices, point of view.

It wears me down but doesn't wear me out.

-Their temperaments could not have been more different.

She was a non-stop chatterbox.

Every account of everyone who knew her, she was gregarious.

She was outgoing, she was chatty, she was fun-loving, she was sociable.

So just a very, very outgoing personality.

And he was the opposite.

There are also some friends who have described his dry spells in using language that could be used to describe clinical depression, by our standards.

Whether or not he was depressed, we don't know, but at the same time, taciturn, quiet.

-Oh, it's a long time between canvases.

I have to be very much interested in the subject.

It's a complicated process.

It has to do with personality, of course.

It's very difficult to explain.

When I don't feel in the mood for painting, I go to the movies for a week or more.

♪♪ ♪♪ -I think the influence of movies on Hopper was tremendous.

Even the phrase that he used where he talked about projecting his feelings onto a canvas.

One movie he always talked about would be the movie "Marty" with Ernest Borgnine, a man who, on the surface, seems to be a very nice, happy-go-lucky kind of a guy.

But underneath, there's tremendous anger and repression.

And, actually, I think he probably identified with the figure of Marty.

But also, if you look at movies like "Strangers on a Train," which is early Hitchcock, the early Hitchcock you see influencing perhaps Hopper.

And then you see later Hitchcock, with something like "Psycho," which Hopper was very amused about actually, where Hopper had influenced Hitchcock.

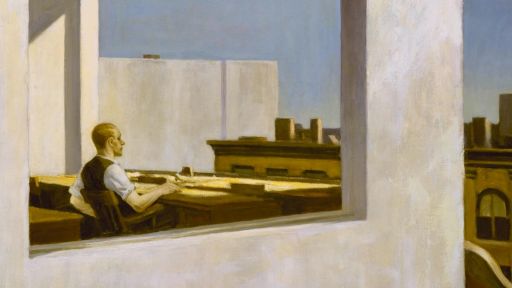

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -The idea for the painting is probably first suggested by many rides on the El train in New York City after dark glimpses of office interiors that were so fleeting as to leave fresh and vivid impressions on my mind.

-"Office at Night" is a remarkable painting simply for the possibility that is there.

What is happening that has allowed these two people to be in this office at the same time?

We are able to build a story around them based on the choice of shoes, the quality of their dress, how tightly it hugs the body and how much is revealed, how sexualized the figures might be based on that.

They are little points of direction.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Jo is turning up in every possible guise.

She had studied drama and she poses like an actress.

She becomes whoever he needs for that particular painting.

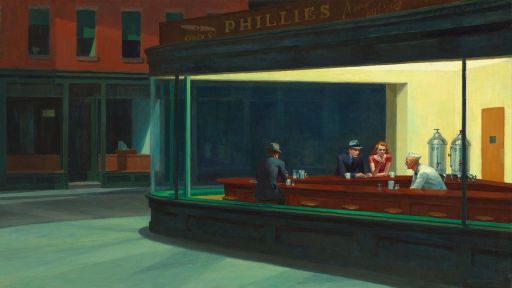

The usherette in New York Movie-House, the girl leaning on the counter in "Nighthawks."

She plays her part.

-"Nighthawks," I think, is probably Hopper's best-known painting.

It's been parodied many times.

And people just love it because there are so many things that don't add up.

And the longer you look, the more puzzling it becomes.

And it's not only, "What are those people doing there in the middle of the night?"

There are no signs on the windows identifying the establishment.

There's no door.

There is no way to join the people in that diner.

And I think its attraction has to do with that enigmatic quality.

-I think he absolutely thought about the viewer in his works.

I think we can think about that in terms of the space.

You are often quite clearly kind of brought into the space.

But also you are rewarded from looking closer and longer.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature.

If this end is unattainable, so, it can be said, is perfection in any other ideal of painting or in any other of man's activities.

♪♪ ♪♪ We like it very much here at South Truro and have taken a cottage for the summer.

Fine, big hills of sand, a desert on a small scale with fine dune formations.

A very open, almost treeless country.

I have one canvas and am starting another.

I'm very much interested in light and particularly sunlight.

Trying to paint sunlight without eliminating the form under it, if I can.

I would like to do sunlight that was just sunlight in itself, perhaps.

♪♪ -They built the house in Truro in 1934.

She inherited some money from an uncle and they used the money to build the house.

They spent half the year there.

The house is very isolated and out on a sandy road.

So, their social engagement, their social life, in Truro was much less than what it was in New York.

They went there primarily for him to work.

And you could tell Jo would fret if they'd been there too long without him having started a canvas.

-In the box are 24 diaries that span the Hoppers' time on Cape Cod.

These are the much more personal viewpoints of Jo Hopper and her way to, I would say, vent about her life with Edward Hopper.

Typically when she's in a good way with Edward Hopper, she calls him Eddy, E-D-D-Y.

If she's not happy with him, she refers to him as the letter "E.," a capital letter "E" with a period, and you will find many more capital E's than you will Eddys in this.

But there are a few instances where she will say something sentimental or nice about him.

But that doesn't happen all the time.

♪♪ -If I could only get to feeling like painting.

I've been out of it so long.

If E would only care!

He keeps saying no painter ever can really take much interest or concern in another painter's output.

Heaven knows I've taken enough concern in his.

♪♪ A little dispute over parking.

E. wouldn't let me finish the job.

I maintained I'd never learn to do anything if he always shoved me away from the wheel when there were any little feats of common sense to be pulled off.

So E. hauled me out by the legs while I clutch the wheel, but he clawed at my arms and I all but sprawled in the road.

♪♪ What has become of my world?

It's evaporated.

I just trudge around in Eddie's.

He'd keep it strictly private if he could, but I have to go somewhere and push hard against the bars.

Privacy!

What becomes of me when he retires into his privacy?

How much better if I still could paint.

That at least would dispose of me.

But he didn't want me to have my ivory tower, lest it in any way hinder him.

-He would be solitary.

He wouldn't speak to her for, in some cases, days on end when he was working.

It was a volatile marriage.

But by all accounts, by the people who knew them, they were a loving couple very devoted to each other.

The volatility of the marriage certainly surfaced over professional matters.

At the same time, she readily embraced the role of his business manager, caretaker.

They never had children.

They married in their early 40s.

So, she fully managed his professional life.

-The studio where Edward Hopper painted was actually in the living room of the actual house.

In the drawings, for example, this is a drawing by Jo Hopper of the potbelly stove that they had inside with a teakettle on the top.

They did not have an actual oven or stove in the house.

They had a little hot plate.

She didn't cook, she didn't like to cook.

If you ran into them in the street, you would probably think that they were at the poverty level.

Their house was very simple and plain.

They lived unbelievably frugally.

I don't think he was a very nice person, especially to his wife.

I don't think he was very nice to people in general.

-I was a houseguest here of Nana and Grandpa Marshall.

When I realized that Mr. Hopper was in the room, that he was one of the guests, I immediately went up to him and introduced myself and told him that I had just finished studying about him in a humanities class that I took at school and I was just so thrilled to meet him.

And his response was so gruff and cut me off in such a way that I just decided that perhaps I'd overstepped my bounds.

-They'd stop by the house, especially around cocktail time.

They'd just kind of show up.

And Josephine would knock on the door and say, "Marie, is it all right if we come in?"

And they'd come in and he never said anything.

I mean, he would talk once in a while, but not very often, and he just let her do her thing and he would, you know, come into the house, sit, have his drink.

Jo, you couldn't shut her up.

♪♪ -E.H. is such a hard-shelled one when it comes to competition.

He has a will to destroy anything that competes with him, if he thinks he can.

I'm such a queer choice to sharpen his claws on.

But a lesser hellcat would give no satisfaction to spend energy on.

♪♪ -People in his paintings rarely interact and rarely touch or anything like that.

I mean, they -- they are separate.

Frequently they don't even look at each other.

And there's this kind of absence of a human narrative.

And that is again, fundamentally, the mystery of how these paintings can be so evocative.

♪♪ -I wish I could paint more.

I get sick of reading and going to the movies.

I'd much rather be painting all the time.

♪♪ -We drove through much wild country going west, marvelous views of miles and miles of sky and mountainside and valley below.

-The Hoppers definitely traveled.

One of the things that they would do is take cross-country road trips from New York to California.

And one of the things that they would do is they would stay in hotels.

And I think a lot of these trips were organized around visits to museums, which were potential places for acquisition.

I think when they're pulled out of their normal routines of, "Here we are in the Cape or we're in New York," they're actually seeing new things that potentially could be inspiring or different.

-From the 1920s through the 1950s, American culture is about movement.

So whether African-Americans are leaving the south to go north, whether you have an increase in immigration and populations wanting to enter the United States, whether you now have highways and cars and motels and the opportunity to travel, this is part of the conversation.

It's very much part of the American dream.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -I love the painting "Seven A.M." Like most of his paintings, you cannot get entry into it.

There is a kind of matter-of-factness and an unimportance about the whole thing.

It's about the idea that so much of our lives are frankly pretty unimportant.

He is talking about the quotidian, the ephemeral.

And, you know, in the end, what does it all add up to?

♪♪ -The loneliness thing is overdone.

From my point of view, she's just looking out the window, just looking out the window.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Hopper's process is so slow and methodical.

It typically took Hopper often about a month to realize a canvas.

Much of the time in between was the thinking, the determining the subject, the sketching, the compositional sketches, and his output is so minimal as he gets older.

Throughout the decades we know from the journals that he would finish a painting and one, two days later would be bringing it to the gallery.

So, there is a sense that, immediately after completion, it was destined for somewhere beyond lingering in the studio.

-The content of your pictures -- I think that some people have seen a lot of psychological elements in it -- loneliness, isolation, modern man in his man-made environment.

-Those are the words of critics, and I can't always agree with what the critics say, you know?

It may be true, and it may not be true.

It's how the -- probably how the viewer looks on the pictures, that they really are.

Could that be?

♪♪ ♪♪ -I think that Hopper painted the city that he felt needed to be or should be represented.

No more, no less.

I don't think Hopper really thought too much about the diversity of the United States.

He didn't think about the migration of people from one region to another.

He painted what he wanted to as an artist.

-The new Negro movement beginning, really, kind of burgeoning in Greenwich Village, the protests that would have been happening through the '50s and '60s.

It's just almost comical for me to imagine Hopper still in his button-down at his easel when you have this great, like, bohemian culture happening right outside the window.

And it's not really reflected in the work.

-I think, in the end, what he really cared about was that his work was shown and that he got recognition and that he was able to sustain himself.

I mean, both mentally and physically.

He did not like being the star in his own movie.

He had no interest.

He would have been happy to disappear.

The only thing is, if you're a 6'5" person, it's very hard to disappear.

-It's hard for the layman to understand what the painter is trying to do.

The painter himself is the only one that can know, really.

He doesn't make any conscious effort perhaps to reveal himself to the public, but that is the aim of painting, eventually.

For many years after I left art school, I had to do commercial drawings, illustrations to make any money at all.

I couldn't sell any paintings.

Then there came a time when I did sell paintings.

Now I sell quite a few.

[ Chuckles ] ♪♪ -The pictures are, in a way, our children, and I always like to know who gets them.

They, these people, are sort of in-laws, but pictures acquired at the gallery, we seldom meet them and are glad to know their names and hope the pictures are happy, hung on white walls if possible and kept out of sunlight that would fade the color.

♪♪ -The whole answer is there on the canvas.

If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.

-Hopper was fortunate.

He lived a long time and remained active through much of that time.

His late work has a number of incredibly profound and moving paintings.

One of my favorites is called "Sun in an Empty Room," and it is exactly what its title says.

It is about light.

It's as abstract as Hopper gets.

It is Hopper's austerity and his distillation of human experience down to the bone.

Somebody asked him, thinking he was being clever, "So what are you after here?"

And Hopper looked at him, and I can only imagine in an exasperated tone, said, "I'm after me."

♪♪ -Hopper has an artistic continuation in terms of influence, how he affects people, artists, painters, visual artists of all kinds, filmmakers.

But in some ways, if you make the metaphor of the subway line, he's a one-way track.

I mean, he's going one place and he did it and he did it brilliantly.

But in terms of the tree of art history, of modernism, Hopper's line really doesn't go anywhere.

It is -- It's its own line.

♪♪ ♪♪ -The "Two Comedians," to me, of 1965, is a capstone for him.

It is the last painting he ever finished that came off his easel before he died.

It is definitely his statement of saying, "I may have not been as supportive as I could."

I think he finally realizes now's the time to really acknowledge all that she contributed to my success as Edward Hopper.

And hence it really is a statement of their creative partnership where she was very much part of the story in producing Edward Hopper for the public, for the audience, and so that public sense of they're taking a bow.

-You know men are not grateful creatures.

-You think not?

-No, I don't think so.

It's women that are grateful.

-Really?

-And who cares -- "Who wants it?

Who cares about it?"

It seems to me that women are the ones that show the gratitude for the little things and big and who remember.

Over the years, they remember.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪