In the first grade, during circle time, when my teacher asked the class what we’d eaten for breakfast, students piped up “Pancakes!” “French toast!” — dishes that had never crossed the threshold of our home, dishes that I’d seen on television and read about in books.

For my immigrant Chinese parents, and much of the world, what you ate for breakfast was what you eat at other meals — you ate what was available, in often lean times.

None my classmates mentioned Campbell’s beef barley soup, a dish my parents considered hearty and convenient, what they could quickly put on the table before they commuted to their engineering and science jobs.

But if I told the truth, I’d be singled out — yet again — as the weird Chinese kid in the suburbs east of San Francisco.

And so, I lied. “Cheerios.”

A few years later, as I began middle school, I paged through the latest issue of Seventeen Magazine, the arbiter of taste for American teens and tweens. To my shock, in between the usual glossy fashion and makeup spreads, I discovered Amy Tan’s “Fish Cheeks.”

In her 1987 story, the narrator’s crush — a white minister’s son — comes over for Christmas dinner with his family. She’s mortified when her parents reach across the table to dip into platters, instead of passing them. Then her father burps to signify his approval of the meal. Only later does she realize that her parents served all her favorites, squid with the look of bicycle tires and a whole rock cod whose head disgusts the squeamish guests.

It was the first time I’d read a short story about a Chinese American teenager. Later, I would learn that Tan is roughly a generation older than me. Her parents were adults during World War II, while mine were very young. Even though the details of our lives differed in significant ways, certain contours were familiar, those of shame and pride and love.

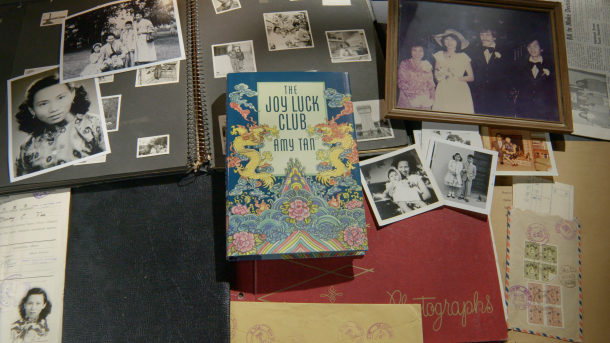

“Fish Cheeks” is now widely taught in classrooms. Within two years of its publication, Tan would debut “The Joy Luck Club,” landmark, interlinked stories about four mothers and four daughters struggling to bridge cultural, language and generational gaps.

With the premier of Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir, I’ve been reflecting upon the impact of her work on my life and many others in the decades since.

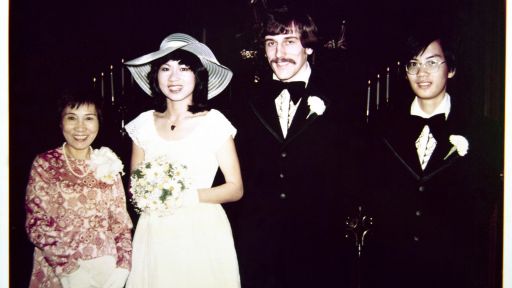

The documentary — which includes poignant photos, home movies, and haunting animation — arrives amid a terrifying surge in anti-Asian violence in this country. The last president and his associates stirred up hate against our community, trying to shift blame for their botched response to the pandemic by variously dubbing Covid-19 the “Wuhan virus,” “Chinese virus” and “Kung Flu.”

It was only a matter of time until the xenophobia would explode into ever greater violence. In March, a gunman killed eight people at Korean spas in Atlanta — six of them Asian women. He couldn’t see them for who they were.

Asian Americans have long been cast as perpetual foreigners, strange and diseased, less than human. From early on, I could sense that suspicion. It was why I lied in circle time and why I would read and re-read the mass market paperback edition of “The Joy Luck Club,” its cover featuring two yellow dragons, stylized waves and flowers, giving me inspiration and hope that I might someday write my own book.

I’d already begun writing stories; like Tan, in my childhood, I would win local writing contests. Becoming a published author — as far-fetched as that seemed — entered the realm of possibility, with the proof of her books in my hands.

My freshman year of college, most of my dorm went to see the film adaptation, which Tan co-wrote.

Lines of dialogue became shorthand, inside jokes for me and my friends, even now, even decades later. Much vividly seemed to involve food: the peanut butter pie that one of the daughters, Rose, intends to make for her soon to be ex-husband — former teen heartthrob Andrew McCarthy. Her mother tells Rose to stand up for herself instead.

The crab missing a leg that another daughter, Jing-Mei, tries to serve herself until her mother intervenes.

Everyone else at dinner took the “best quality” crab for themselves, her mother says while they’re cleaning up. “You took worst. Because you have best-quality heart.”

Is it any wonder that so many of us sobbed in the movie theater?

Tan inspired me and so many others who followed to write the stories that only we could tell.

Eventually, I became a writer, publishing “Deceit and Other Possibilities,” a short story collection, and a novel, “A River of Stars.” My next book, “Forbidden City,” is forthcoming.

A couple years ago, I met Tan at the Community of Writers, a conference where we both got our start as aspiring novelists, decades apart. I still had that battered copy of “The Joy Luck Club,” that I’d carried with me on several cross country and career moves.

Heart pounding, I approached her one night, not wanting to bother her, but she graciously signed it, as she has signed countless copies of her novels, children’s books, and memoirs for fans who felt made visible, made whole by her work, whether or not they shared a similar background.

Recent Chinese American narratives have moved away from World War II as a defining historical moment in the lives of their characters. History has marched on, contemporary economic and social forces are giving rise to a new generation of diasporic literature — including C. Pam Zhang’s “How Much of These Hills is Gold,” Charles Yu’s “Interior Chinatown,” Kirstin Chen’s forthcoming “Counterfeit,” Celeste Ng’s “Little Fires Everywhere,” K-Ming Chang’s “Bestiary,” Yang Huang’s “My Good Son,” Jean Kwok’s “Searching for Sylvie Lee,” and movies — such as Kevin Kwan’s “Crazy Rich Asians” and Alice Wu’s “The Half of It.”

Recently, Asian America cheered when the Beijing-born, U.S. educated Chloé Zhao became the first woman of color to win an Oscar for best director for “Nomadland,” which also won as best picture, and Korean star Youn Yuh-jung, whose two sons are Korean-American, won as best supporting actress in “Minari.”

The more examples I consider, the more I realize I’m leaving out, including stunning Chinese American poetry and nonfiction, and the vast wealth of Asian American writing. This narrative plenty — riches I could only dream of when I was a child — lessens the burden of representation saddled on a work when it’s considered the first of its kind.

May these stories give rise to even more.