Historian Bill Doggett reflects on the influence of Black women on American music, from the earliest recorded spirituals to today.

. . . Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

. . . Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

. . . a long ways from home.

The poignancy of the opening words of the Negro Spiritual belie a deeper multigenerational trauma experienced by enslaved African women and children. It is a trauma that represents a collective cultural memory forced into a state of transformative resilience by generations of enslaved African women who dared to survive. Stolen African women who survived the Middle Passage in dark, disease-ridden bellies of slave ships did so against all odds. They embraced an audacity of hope to believe that uncertain futures might be found in a strong faith anchored in the cultural memory of song and spirit God tradition left behind but never forgotten.

West African songs of worship, celebration, work and sorrow found a transmigration in the diaspora of Cuba, Haiti, Brazil and the Colonies. The Slave Song later known as the Negro Spiritual is a song and statement of resilience and belief in a better day often sung by women in the fields, the secret brush harbors and after sundown gathering places. These songs were coded with messages inspired by biblical Old Testament stories of the Hebrews. Enslaved Africans required to attend church services of their masters identified with the stories of the enslaved Hebrews, seeing their own plight as those of the biblical Hebrews.

“Go Down Moses,” “Steal Away” and “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” are coded spirituals. They were associated with courageous women, abolitionist former slaves Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and other women who escaped slavery only to return to the Deep South as “Underground Railroad” operators.

Although early recorded sound prioritized the documentation of Black male quartet ensembles, women had always been at the epicenter of the singing in the fields and in the slave cabins. Black women would break the gender glass ceiling in early recorded sound in 1919 with the first recording of the Negro Spiritual, “Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen.” It was performed by the turn of the century classically trained soprano, Florence Cole Talbert.

Talbert was the first Black woman to make a sound recording for the short lived boutique label of Boston area Black businessman and classical music aficionado, George Broome. For Broome Special Phonograph Record, Talbert recorded three sides, two of which were Art Songs by European composers.

Talbert’s recordings would inspire a whole generation of Black women to record, beginning in 1921 with the founding of Black Swan Records, the first significant Black record label focused expressly on documenting black talent. Talbert made her next recordings with Black Swan Records in the 1922 Red “Concert Swan” series.

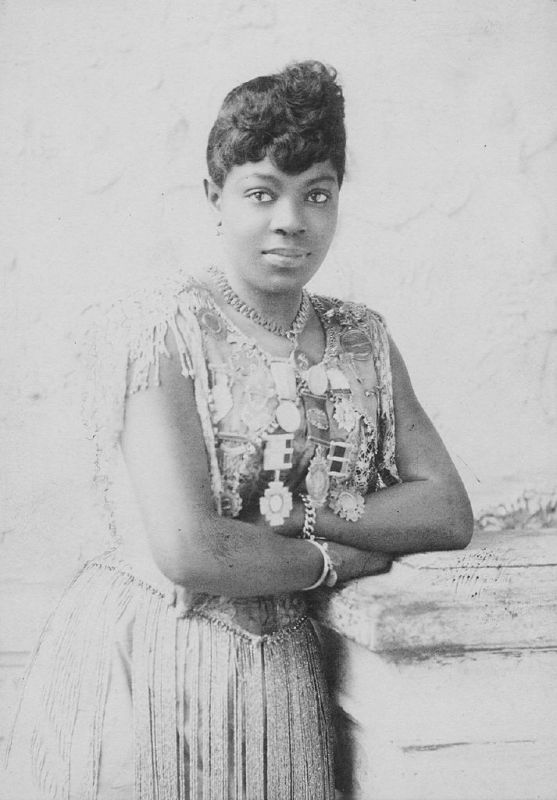

Talbert and Garnes were the operatic stars of Black Swan Records’ “Concert Series.” Women’s voices played a central role in the recorded catalog. Artistic exceptionalism of women as a source of racial pride is at the epicenter of the label name, Black Swan. Black Swan was the name given to the most important classically trained Black woman who concertized in pre-Civil War America, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield. Greenfield inspired Sissieretta Joyner Jones, a Black concert singer who defined artistic exceptionalism at the dawn of the 20th century. Although Jones never made a sound recording, her artistic reputation inspired a new generation of Black women, from Florence Cole Talbert, Revella Hughes, Antoinette Garnes and Hattie King Reavis to Marian Anderson, who emerged out of the shadow of the Great Migration and the first World War.

Although the young Marian Anderson, whose reputation as “the baby Contralto,” was significant during 1921-23, she did not record for Black Swan Records. In December 1923, Victor Records recorded her in two Negro Spirituals: “Deep River” and “My Way’s Cloudy.” These recordings launched a critical legacy that signaled the most consequential Black woman to record in the 20th century. Yet sound recordings by Black female ensembles remained few and far between. Notable in that exception are two: the Virginia Female Jubilee Singers and the Wheat Street Female Ensemble.

The Virginia Female Jubilee Singers recorded two songs in September 1921 in New York, according to “Discography of Okeh Records, 1918-1934.” Described as a “colored female quartette,” their vocal style is associated with a famous style of singing connected to the Tidewater region in Virginia. On a single two sided Okeh 78rpm recording, they performed the Civil War associated Slave Song, “Mary Don’t You Weep,” and “Lover of The Lord.”

Tragically, little is known about their history or names. Yet their voices and contributions survive through these recordings. A similar story also befell the Wheat Street Female Quartet, an ensemble based in Atlanta, Georgia’s historic Wheat Street Baptist Church. They were the nation’s pioneer in the emergence of women in the hitherto male exclusive Jubilee Quartet genre.

Their first recordings for Columbia Records were recorded in Atlanta in 1925. Although there are no records of their names in the recording logs and their names have yet to be identified in the church’s historic documents, the Wheat Street Female Ensemble recorded for Columbia Records in 1925 and Okeh Records in 1926.

The Wheat Street Baptist Church later became known for featuring various gospel and quartet programs in the 1940s and 1950s. Like The Virginia Female Jubilee Singers, their sound mirrored the sound of the all male Jubilee Quartets with the female Jubilee version of tenor, baritone and bass.

In three sessions, they recorded the Negro Spirituals such as “Go Down Moses,” “Wheel in the Wheel [Ezekiel Saw the Wheel],” “My Way is Cloudy,” “Religion is a Fortune,” “When the Saints Go Marching In” and “Oh Yes.” The Wheat Street Female Ensemble set an important precedent for Black women as song evangelists who as solo artists or as Jubilee ensembles would impact ideas about the role of women in recorded song, in the recording industry and most importantly, the sound and substance of American music.

Solo Gospel artists emerging in the late 1930s-40s, such as Mahalia Jackson and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, made their mark for artistic exceptionalism of Black women as solo artists. It was not until the early 1950s that all female Gospel Harmony ensembles including Sallie Martin Singers, the Angelic Singers, the Clara Ward Singers, Dorothy Love Coates and the Original Gospel Harmonettes and Doris Akins and The Simmons-Akers Singers would correct the invisibility of the 1920s Wheat Street and Virginia Female Singers with a critical media presence through recordings, radio and TV show broadcasts.

These dynamic ensembles set the stage for the arrival of Sweet Honey in the Rock in the 1980s-90s. With an audacity of hope and an undeterred resilience, Black women as concert singers, musicians, gospel and popular music artists transformed the landscape of American music. Collectively, they broke glass ceilings of gender limitations that inspired the opening of new doors of aspiration and transformative leadership by Mary McLeod Bethune, Coretta Scott King, Dorothy Height, Shirley Chisholm forward to Michelle Obama.