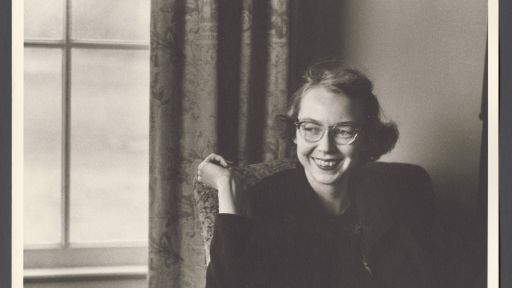

Flannery O’Connor in the driveway at Andalusia, 1962. Photo: AP Photo/Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Joe McTyre

The writer Flannery O’Connor was known for her dark, funny and sassy stories about misfits, outsiders and the types of offbeat characters she encountered while living in the American South. O’Connor herself could be considered a sort of outsider. Plagued by symptoms of lupus in the latter part of her life and mostly bound to the farm where she lived with her mother and many peacocks, she often wrote about themes of isolation and created characters driven by desires to connect with each other, society at large, or with God. Her stories, which have inspired many writers and readers over the years, were also imbued with a kind of dark humor and exploration of faith and mortality that was often attributed to her illness.

“Flannery O’Connor’s life in some ways could have come out of a Flannery O’Connor story,” said contemporary writer Alice McDermott, who was influenced by O’Connor’s work. “It was the illness I think that made her the writer that she is.”

Born Mary Flannery O’Connor in Savannah, Georgia, to an Irish Catholic immigrant family, the young writer was largely encouraged to write and draw by her father, who died of lupus when she was 15 years old. There remains no cure for the disease – only treatment of its symptoms. It was a turning point for O’Connor.

Devastated by her father’s death, but also motivated to pursue her literary ambitions, O’Connor began studying writing during World War II in Georgia before attending the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and then being admitted to the famed Yaddo writing program in Saratoga Springs, NY. O’Connor dropped her first name, Mary, around this time. After her time at Yaddo, O’Connor remained on the East Coast for a while longer to write her first novel, “Wise Blood” (published 1952).The family she was boarding with at the time, Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, remembered that one day, O’Connor told them: “I think I’d better see a doctor, because I can’t raise my arms to the typewriter.”

When O’Connor returned to Georgia to see a doctor, he diagnosed her with lupus, but only told the diagnosis to O’Connor’s mother, Regina.

“Her mother, knowing that the father had died of the same disease, thought that the shock would be too great for Flannery and decided not to tell her,” said Sally Fitzgerald. “[Flannery] lost her hair. She was rather disfigured by the medicine. It could be combated, although not cured, by cortisone. This is the way she was able to live as long as she did.”

In 1951 when O’Connor became intensely ill, she continued to think it was merely arthritis that was bothering her. She moved out to the family’s dairy farm with her mother. By then, O’Connor was using crutches to get around. Both women lived on the ground floor of the home so that O’Connor had no need to climb the stairs.

At the farm, O’Connor continued writing religiously. Every morning, seven days a week, never taking a single day off, even Sunday. Being confined to the farm, O’Connor also began finding her material and characters in her environs.

“After she got sick, she was a prisoner of her body. I think she loved writing so much because it freed her from the corporeal,” said the writer and theater critic Hilton Als.

“She realized that she didn’t have to sit in New York and lose her ear for Southern speech, that she had it everywhere. The farm women, the farm people,” said Fitzgerald.

One day, as Fitzgerald was driving O’Connor around to do errands, Fitzgerald revealed her lupus diagnosis.

“She said something again about her arthritis. I said, ‘Flannery, you don’t have arthritis. You have lupus.'” Fitzgerald recalled. “Her hand was shaking. My knee was shaking on the clutch.

“We drove back up and down the road, and a few minutes later she said, ‘Well, that’s not good news. But I can’t thank you enough for telling me. I thought I had lupus. And I thought I was going crazy. And I’d a lot rather be sick than crazy’.”

O’Connor launched herself into writing with even more fervor. Her friends and acquaintances who knew her around this time noted that she rarely complained about her illness and was usually in good humor.

“One of the few signs of Flannery’s lupus was the fact that after the midday meal, you could see her tiring,” said friend Louise Abbot. “The cortisone derivative that she took, which saved her life, had softened the bones and also had put her on crutches and this had altered her appearance. But she was wonderfully animated when she was interested in what she was saying, when a good question was asked and she could answer with zest.”

“I’m making out fine, in spite of any conflicting stories,” O’Connor wrote around this time. “I have enough energy to write with, and as that is all I have any business doing anyhow, I can with one eye squinting take it all as a blessing.”

While outwardly coping with her illness, O’Connor’s writing began reflecting the suffering, both physical and mental, she was undergoing at that time. The work that came next, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find,” a collection of short stories, was a critical and literary success that changed O’Connor’s reputation and popularized her work.

“She looks at the darkness unflinchingly and she approaches it with clarity and with precision. And that I think is her greatness,” the writer Mary Gordon said of O’Connor’s work. “I think that it’s inevitable that her dark view of the body and not nature, but the bodily world as being only a source of dark things, has to be connected to her lupus. The deformed body, the broken body, the afflicted body is very much a theme that recurs in her work.”

Her work reflected flawed characters who interacted with disabled characters in what she herself referred to as “grotesque” scenarios and often violent narratives. But O’Connor also used that violence as a vehicle for internal transformations for her characters who were in pursuit of God’s grace — a way to explore religion and morality through the grotesque.

“Grace changes us and the change is painful,” she wrote in one of the letters she exchanged with a friend during this time.

“In some ways, I think we can say now thank God for her suffering, because it allowed her to produce the work that she produced,” said McDermott.

By 1965, as O’Connor was putting together her collection of stories, “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” her editor Robert Giroux said he knew he was “working with a dying writer.”

“She was in the hospital in Atlanta. It was, in a way, it was in kind of a horror story because she was so anxious to get the last story, ‘Revelation,'” Giroux said. “She wanted that to get in.”

O’Connor died on August 3, 1964 at the age of 39, some 12 years after her diagnosis. Her body of work includes two novels, at least 32 short stories and numerous essays. There have been multiple film adaptations of her work and she even won a posthumous National Book Award for Fiction in 1972 for the “Complete Stories” book that was compiled after her death, providing an enduring legacy for this unique writer for generations to come.