You could start with her piano playing. In “The Ballad of Sad Young Men” from her debut album “First Take” (1969), you could say it’s warm, but wistful, holding on to jazz roots and torch songs played in quiet rooms. You could say it’s funky and bluesy, the way it is on “Compared to What” from that same album. You could start with her voice. Her version of “What’s Going On” from the 50th anniversary release of her 1971 album “Quiet Fire” is contemplative, soft but forceful.

Her extended cry as she elongates the phrase, “Mother, mother everybody thinks we’re wrong.” Or say it’s heavy with love and regret like “I (Who Have Nothing)” from her 1972 album with Donny Hathaway, tinged with gospel, blending into the sound that made her and Hathaway such a powerful duo.

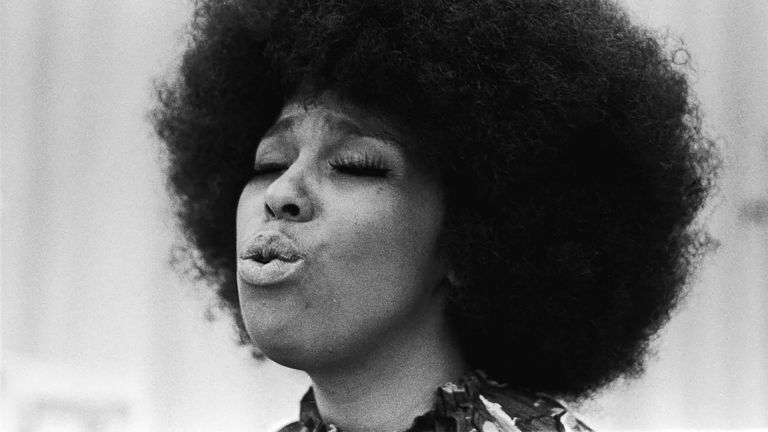

The thing about Roberta Flack is that she is all of those things, all of those voices, all of those sounds. She is an artist that has been defying, crossing and blending genres from her very first album. She is truly and authentically herself in everything she does.

“You have to unzip yourself, say, ‘Here’s what I’m like inside,’” she told Vogue in 1970. “Then all tensions, aches, disguises, holdbacks are gone. This is me, world; you can dig it or not.”

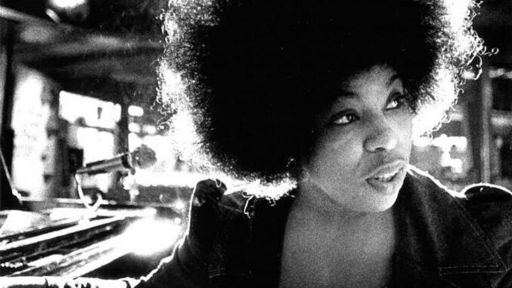

Bill Eaton has a theory. The singer, songwriter and one-time arranger for Roberta Flack believes that one way you can tell a great artist, a really great artist, is that “the audience leans forward.” Maybe that’s in anticipation, waiting on the edge of a song for the next note. But for an artist like Roberta Flack, that lean forward is something more. That lean forward is because a boundary has fallen away, and the audience is shifting, coming closer, her to them, them to her, until the song, the singer, the spectator, the moment is all one.

Roberta Flack has a way of erasing spaces.

It’s not that she is us or we her. It’s that, for a brief second, it’s all everything. It’s soul, jazz, funk, classical. It’s gospel, blues, rock, folk. The audience leans forward to take it all in, to breathe it all in.

Roberta Flack is at once intimate and inviting, a moment you shouldn’t see, but one you have to see. In his essay “The Sound of Velvet Melting: The Power of ‘Vibe’ in the Music of Roberta Flack,” writer Jason King calls it “her ability to use her voice and complementary musical skills to traffic in ‘vibe.’” And that vibe is the thing you can’t see, but you can hear it, feel it. The vibe is the leaning in, closing in the space between you and the music.

It’s been like that since the beginning of her career, a career that, intellectually, we know was the result of hard work, but emotionally feels like she appeared from the ether, landing at just the right musical moment. There was just something special about her. In a 1970 article in Essence Magazine, Les McCann, pianist and the one credited with bringing Flack to the attention of Atlantic Records, said her voice “touched, tapped, trapped, and kicked over every emotion I have ever known.” When it feels like that, when it sounds like that, it’s called soul.

But even something so beautiful and expansive as soul hardly feels big enough to contain her music.

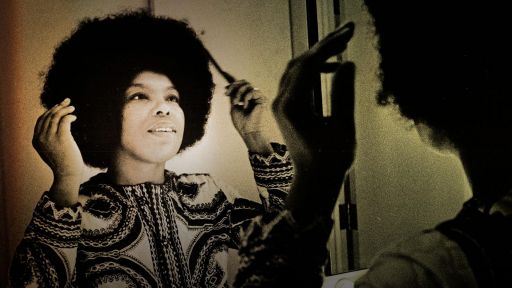

Just three years before her 1969 debut “First Take,” Roberta Flack hit singer was Roberta Flack music teacher. After leaving Howard University, Flack began teaching in her home state of North Carolina. It was an underfunded, under-resourced Black school in Farmville. “There was no piano in my classroom,” Flack recalled in a 1971 interview in Ebony, “I went from room to room with a pitch pipe and autoharp, teaching them music.” Music was always something she shared, whether it was classroom to classroom in rural North Carolina, or in her trips back to Washington, D.C. that she made every weekend. There, she studied to get her teaching certification in the District, and picked up various music gigs. She directed choirs, taught voice lessons, and in the job that could be considered her origin story, filled in as the piano player to accompany opera singers at the Tivoli Opera Restaurant in Georgetown.

She could do that. She was classically-trained, after all, studying the masters—Bach, Beethoven, Rachmaninoff. “I studied voice with opera singers, and studied classical piano,” Flack said in a 1973 interview with NME. “I’m saying this because I want people to know that I’ve worked hard.” But the space at Tivoli became too small for a talent as expansive as hers. The restaurant was bought by Henry Yaffe, and once he heard her voice, he knew. He invited her to play every Sunday at the newly-renamed Mr. Henry’s, each week her crowd and reputation building. He eventually built Flack her own space in the club, a space where she could mesmerize audiences night after night with her blend of sound and emotion.

Here’s where the words get difficult.

Here’s where they fail, again and again, to describe her music. It’s easy to slot her into “soul” because that’s where you feel it. That space where the music fills all of the empty, warms the cold, eases the painful—that’s soul. But as a musical genre, soul is more complex. In her book “The Sound of Soul: The Story of Black Music,” music critic Phyl Garland puts it this way: the sound of soul is “manifest in the overlapping forms of blues, jazz, gospel and popular music. Its essence is indisputably Black.” And without even much thinking, that’s Roberta Flack.

Listen to “Gone Away” from her 1970 release “Chapter Two.” She comes in with a heavy softness, contradictory, sure, but that’s what it sounds like to cross boundaries. A slinky, jazz-inflected bass plays against dramatic strings, then the song eases into an easy funk groove, pushing and pushing to a joyful choral-like ending punctuated with psychedelic guitar. It’s evident in her gorgeous, nearly 13-minute rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “I Can See the Sun in Late December” from her 1975 album “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” A musical journey so thoroughly intense that it’s easy to see why Les McCann’s emotions took the ride they did.

You could almost imagine being in that audience, the one perched there on the edges of their seats, in that upstairs room at Mr. Henry’s, feeling her shifting musical boundaries note by note. How do we describe the sound of a person who is undeniably soulful, yet has these curves and edges that were honed, not by just soul, but by classical, by pop, by opera, by folk? Flack herself explained it this way in her Essence interview, “I grew up just loving music. All kinds.” And that’s what you hear in her music, an artist shaped by the sounds around her.

“When I played, that’s when I felt the presence of God,” she told an interviewer once. And maybe that’s what her sound is—ecstasy in its most pure sense. Maybe that’s why the audience leans in; they want to bear witness to an artist seeing the face of something powerful, and for just a minute, maybe even for just one note, they feel that power too.