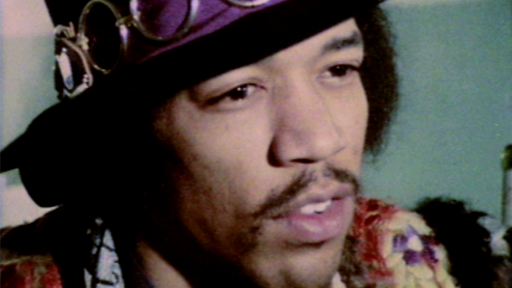

Portrait of Duke Ellington and Sonny Greer, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov. 1946 (LOC)

Photo: William P., Gottlieb

The legendary jazz composer Duke Ellington used music as a subtle, but compelling way to tell stories of racial injustice to wide reaching audiences.

Rising through the ranks from a small time performer in Washington, D.C. and Harlem, to an international sensation adored by white and Black audiences alike, Ellington was a musical revolutionary.

Here are 5 lessons on race, music, and America that we can learn from Duke Ellington.

1. Ellington viewed music as a form of activism.

“You can say anything you want on the trombone,” Ellington said in a 1944 profile in the New Yorker, “but you gotta be careful with words.”

Ellington was born Edward Kennedy Ellington in Washington, D.C. in 1899, to parents James and Daisy Ellington. At the turn of the century, D.C. was a considerably safer place for Black Americans than other parts of the country. The city boasted the largest Black urban community in the country, with 31% Black residents, and racially discriminatory laws were rarely enforced. Still, it was far from an anti-racist haven, and Black communities endured segregation and racial injustice daily.

The teachers at Ellington’s segregated school went out of their way to teach Black history in America, and to instill a deep sense of pride in their Black students. Black community leaders did the same. Ellington and his classmates were taught that the best way to fight injustice wasn’t through violence, but through high achievement. As described in the book “Duke Ellington’s America,” “the community’s Black leaders did not so much fight against the racial system in America as quietly and determinedly circumvent it.” This idea played an enormous role in how Ellington thought about – and used — his music. He used his achievements as a musician to bring attention to the racial injustice and violence in America.

“The music of my race is something more than the American idiom,” Duke Ellington once wrote in an article for British magazine, Rhythm. “It is the result of our transplantation to American soil, and was our reaction in the plantation days to the tyranny we endured. What we could not say openly, we expressed in music.”

Ellington knew that music could reach people in a way that words simply could not. While Ellington knew the power of words (he was a poet and writer himself, though he rarely published his writings), he also knew that white people were more likely to listen to music by a Black musician than read the revolutionary writings of a Black activist. Playing for white crowds gave him the opportunity to spread his message widely to audiences of all races.

2. He wanted to be regarded as an artist first.

When a journalist asked Ellington what he thought of the music of “his people,” Ellington responded matter-of-factly, “That’s a strange question. You know, I was afraid you were going to do this — get me out here on this tape and expose me to my own ignorance or something. My people, now which of my people, you know? I’m in several groups — I’m in the group of the piano players, I’m in the group of the listeners, I’m in the group of those who have a general appreciation of music, I’m in the group of those who aspire to be dilettantes, those who attempt to produce something fit for the plateau.” Ellington pauses, laughs, then continues, “I’m in the group of those who appreciate Bourgogne. I had a strong influence by the music of the people. The people, the people, rather than my people, because the people are my people.”

Ellington wanted to be recognized as more than simply a Black musician. While he was proud of his identity, he felt that being boxed into the category of a “Black musician” was limiting and prevented him from being taken seriously as a conductor. Ellington often waved off questions about his race or his relationship to jazz as a Black musician. Instead, he turned his attention to the music and let that speak for itself.

3. He used his appearance to subvert racist stereotypes.

Ellington went out of his way to look the part of a debonair, elite conductor, complete with dapper suits and slicked back hair. When Ellington’s band was invited to play in big-time Hollywood films, his presentation meant everything.

Duke Ellington graced the screen as a suave, big time conductor – commanding the room with his music. This portrayal in Hollywood films was starkly different than how Black people were usually portrayed. Ellington’s movies became a point of pride for Black audiences.

At that time, Black Americans on the silver screen were portrayed as lowly laborers, household help, or as racist and cartoonish caricatures. In contrast, Ellington’s appearance and his music, which was popular among white audiences, shattered many stereotypes and barriers.

4. He broke down racial barriers with his performance of “Black, Brown and Beige” at Carnegie Hall.

Never was Ellington’s impact more profound than at his Carnegie Hall performance on January 23, 1943. That night, in the highly anticipated premiere of his major jazz composition, “Black, Brown and Beige: A Tone Parallel to the American Negro,” Ellington appeared before an interracial audience from a range of different backgrounds, which included among them working-class Black Americans and celebrities like Frank Sinatra. A Black man in the 1940’s, Ellington commanded the audience’s undivided attention on the world’s biggest stage, dressed to the nines, as he conducted his piece about the horrors of slavery and the post-slavery challenges of Black America.

His performance was revolutionary. By taking the stage as a conductor and performing a piece of music he wrote specifically about the Black struggle, Ellington was making a statement larger than the music itself. He took the lessons he had learned as a child to use his own platform and achievements to fight racial injustice, and put them into practice at the highest level.

5. He used “Black, Brown and Beige” as a means to share the stories of the Black experience.

For years before the Carnegie Hall premiere of “Black, Brown and Beige,” Ellington had hinted at the dream of creating a piece meant to showcase the pain and struggle Black Americans had endured since their capture from the shores of Africa.

In “Duke Ellington and ‘Black, Brown and Beige’: The Composer Historian at Carnegie Hall,” author Harvey G. Cohen writes that Ellington had spent years dreaming of and creating versions of the final piece. He told one journalist in 1941 that he was in the final stages of a libretto about Black history, explaining “I wrote it because I want to rescue Negro music from well-meaning friends… All arrangements of historic American Negro music have been made by conservatory-trained musicians who inevitably handle it with a European technique. It’s time a big piece of music was written from the inside by a Negro.”

After using the stage at Carnegie Hall to introduce “Black, Brown and Beige,” he reworked a longer version, detailing the Black experience in even more depth, for an album of the same name in 1958. The album is commonly thought to be divided into three sections.

The first section, “Black,” pays homage to American slaves. It begins with a work song and sways into a heart aching hymn of longing. The second section, “Brown,” follows the emancipation of slaves into the Jim Crow era, and all the way through the two world wars. The war section is meant to highlight the sacrifice of Black soldiers who valiantly fought for the same country that had stolen their lives and their history. The third section, “Beige,” Ellington explained, is about the Black Americans who “still don’t have enough to eat or a place to sleep,” in spite of the progress that’s been made. Ellington’s hope for the composition was that it would educate and unify.

For “Black, Brown and Beige,” Ellington wrote accompanying essays, consisting of 29 pages of text, in order to make his message clear. Particularly haunting were Ellington’s lines in “Beige,” which read, “Who brought the dope / And made a rope / Of it, to hang you / In your misery…/ And Harlem…/ How’d you come to be / Permitted / In a land that’s free?” Through lyrics like these, Ellington challenged his many white fans to grapple with the segregation and violence that Black Americans continued to face, and reminded them that the fight was far from over, and the voices of Black America would not be silenced.