TRANSCRIPT

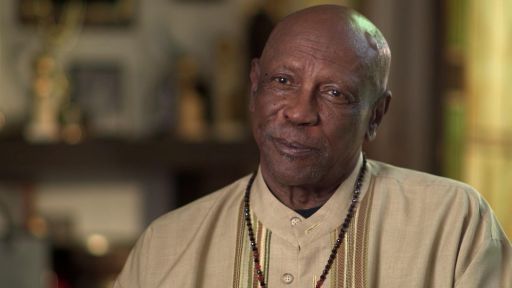

I think that anybody who is African American is born into a set of circumstances that are hugely suffocating and extremely difficult to live in.

And I think all of us are put upon to find out ways and methodology to survive and to get through and to overcome those conditions.

When I was a boy growing up, and for that matter, almost all of America, was consistently and persistently being fed a diet of image that was wholly unacceptable to us.

In the movies, we were servants.

We were second class citizens.

We were buffoons.

We were the brunt of and the object of everyone's disdain and benevolence.

We seemed to have always been portrayed as a people without intellect, without purpose, without history, without dignity.

And I think anyone who was born into those circumstances, who saw the slightest glimmer of opportunity to change that canvas, would have to make the commitment, at least morally and ethically, make the commitment to try to use that opportunity to in fact, change the canvas.

'Cause usually when that opportunity is afforded you to make that change, it's a double edged sword.

It's either an opportunity that can be used to be self-serving, to just do what is minimally necessary, to get on with life, but sustaining some kind of relationship to the dominant community or to those whom you were serving that would never wrinkle them, would never cause them any discomfort.

So what you did was you became the good house, and that famous word, you know, you became somebody who was always going to behave in a way that would make you acceptable.

Well, sometimes that was not enough.

Being acceptable more often than not meant that you robbed yourself of your birthright.

You trampled on your dignity and you turn your back on your own struggle and your own people.

This was more or less the broad images that were out there, constantly being referred to as 'the Negro'. That is what they do.

That is how they are.

And very few people walked a walk that was different to that cadence.

Along comes Paul Robeson, along comes Joe Lewis, along comes Duke Ellington.

Handful of people in that time who rose above that image, who had purpose, who had intellect, who had dignity, who had talent, and decided to put it on the line.

I did not come to meet Paul Robeson until shortly after my service in the United States Navy during the Second World War.

I had been honorably discharged, and like a host of young men, African Americans, we had had huge expectations that America would be more friendly and a more compassionate and a more rewarding place to be.

Especially since we had demonstrated our courage and our willingness to fight for this country and for the ideals that it had set for itself.

And when I came out of the Navy, I discovered that that generosity was not quite as available as we had hoped.

As a matter of fact, it was quite distant.

And in looking for where to put my life and what to do with it, a set of coincidences led me to the theater.

And when I was very young, I walked into a community theater in Harlem called the American Negro Theater, made up of a host of wonderful people who were writers and directors and actors and scenic designers.

And as a member of that group, we had undertaken to put on a play written by a great Irish playwright by the name of Sean O'Casey.

And we had translated his work into the Black environment.

It was a play written about Ireland and the Irish rebellion against the British.

I played a role in it.

And during the first week of the play, one evening, word came backstage in this tiny little theater that Paul Robeson was in attendance.

And just the thought itself overwhelmed us.

And I'm not quite sure how we got through the play.

Anyway, at the end of the evening, Paul Robeson stayed behind.

He was introduced to the cast.

He spoke to us in powerful, warm, embracing terms.

He applauded the work we were doing.

He felt that the kind of theater we were trying to put out was just what the Black community in America needed.

And that art in the service of that kind of theater was art its best.

And that he himself had tried to use his life in exactly the same way as we were attempting to do, although we were all much younger.

At the end of that evening, he spent a bit of time with us.

At the end of when he left, I remember that for many weeks thereafter, his words and his presence and his gentility had a profound impact on me.

I was still in the search for life.

Here I was, 20 years old, 1920, wondering where to go, looking for whom I could identify as the person to most light the way, so to speak.

And all of a sudden this person landed in the middle of my life that brought an awful lot of solution to a lot of annoying and nagging questions.

Where do Black people go?

How do we use ourselves?

What do we do?

Can you beat the overwhelming odds of what's out here?

Everything you could possibly think of, that were questions for those of us who'd like to get on with life, came answered in the embodiment of this one man.

The first positive sounds I ever heard about Africa came from Paul Robeson, along with Dr. Dubois, were the only two, but Robeson as an artist was the one who sang songs in Swahili that came from Africa, who spoke of the noble nobility in African history, of kings and emperors and conquerors and men who designed the charts that could put the world in mobility, the stars, and talked about Timbuktu.

And all of which I never heard of, knew very little about.

Outside of slavery and slave history from which all was measured, it was Robeson who had put on the table for me that there was a linkage somewhere in the past that had never been available to me, that had to do with the nobility of Africans.

There were two choices that one could make.

Maybe there were more than two, but there were certainly two very clear ones.

One was to do the art of Eurocentric, a choice, the Eurocentric value, the Eurocentric roots which many chose to do, and try to do that art in as perfected a way as you possibly can.

There's one thing that's gonna always be true about that fact or that choice.

And that is that you'll never touch the soul of who you are, because that's not what you inner soul is experiencing or where your inner soul lives.

Every attempt to do something that spoke to the greater truth and the greater glory of what our inner souls were about were always being denied us.

'Cause it was what the other society did not want to hear.

When Robeson came upon the scene, he clearly was able to do the former, easily.

Could read music, he could sing.

He had a voice, he could do Othello, which was written by William Shakespeare, and he could certainly do other things.

But when it came to his own art of his people, when it came to that which he understood more profoundly than anything else, he had to find a way to put that before, not only the people from whom the music came themselves, who had never had a chance to hear it, in many of the ways it should have been heard, 'cause they were hearing it also the way white folks wanted them to hear it, or the other society wanted them to hear it.

So it had to be interpreted for them as well.

What Paul did very consciously, was to go into that world of Black life, Black art, extract from it those songs that he felt most comfortable with, and he felt were the one that most demonstrated our history, our struggle, and our dignity as a people.

Certainly embodied in the world of spiritual music, of religious music was an awful lot of that for the simple reason that since it was in fact the only music that we were permitted to develop that the white world, that our slave masters would permit us to perform, we had to use it to house all of our aspirations and all of our thoughts, 'cause it was the only vehicle.

So that when you look at spirituals, you look at religious music from the Black community.

It is not just about the praise of God and the presence of Jesus.

It is also about how we were pained, how we were crucified how painful life had been to us, how we struggled, what our hopes and aspirations were, were all contained within the spiritual.

We sang with metaphor.

We sang with double meaning.

So when I began to integrate experiences that were very close to my own life.

I was born in New York in Harlem, but on and off the first 12 years of my life were deeply rooted in the island of Jamaica.

And those early years left a huge impression on me with the culture of the region.

And when I started to sing about it, I had to take a lot of things into consideration.

(coughing) Excuse me.

First of all, the popular definition of the music of the Caribbean was that they were happy-go-lucky people.

The men loved to drink and sit onto the coconut trees, lazing their time away, completely preoccupied with their genitalia.

And they would like to sing about their sexual powers.

And mostly they also dislike their history.

They dislike their Blackness, and they speak about women in really rather demeaning and derogatory terms, which was central to the humor of the Calypsonian art.

In fact, there was a whole other side to the culture of the West Indies that nobody paid very much attention to, except those who lived in the community.

So that whenever I talked about singing the songs of the West Indian, of West Indian life and people, people always thought, oh the calypso is coming, and there's gonna be some song filled with double entendre and about the sexual delights and drinking delights, of experiences in the Caribbean.

No, but I, knowing what Paul had done with the songs of the workers, with the songs of those who were rebelling against depression, gave me an opportunity to find the songs in that repertoire from the Caribbean that would help me do the same thing.

As beautiful and as powerful as 'The Banana Boat Song' has become, it was a conscious choice.

'Day-o, day-o, daylight come and we want go home.'

'Work all night on a drink of rum.'

It is a classic work song, it spoke about the struggles of the people who are underpaid, who are the victims of colonialism.

And in this song, it talked about our aspirations for a better way of life.

This is central to the story of 'The Banana Boat Song.'

Its delight is the fact that it was done so skillfully in the poetic way in which evolved, and the music is so lilting.

This then led me to other songs, 'Jamaica Farewell,' certainly the first song, one of the first songs I ever attempted to write and co-author with two other men, one by the name of Bill Attaway and the other by Irving Burgie, was the song called 'Island in the Sun,' which became hugely popular.

But it was a song that spoke to the hopes and aspirations of the people of the Caribbean region who were of African descent.

All of this existed and held for me great clarity because Paul Robeson had set a glorious pace from which we could all draw sustenance and draw example.

He had extended to me the invitation to help his son, Paul Jr., and others celebrate his 75th birthday.

And he petitioned to see me.

And I went to Philadelphia for the first of a series of meetings that stayed in place until his death.

And I saw him for the first time in a very, very long time.

And he was still Paul, but he was physically very different, much thinner, bit older, the illness and the emotional stuff he was going through was obviously taking its toll.

His speech was clear, but halting, and he sat and went into moments of reflection, and you worked with his rhythm.

And as saddened as I was to see this being part of the way in which his life was being concluded, it was also very rewarding to have had the opportunity to not only see him again, but to know that behind all of this physical, disintegration is too hard a word, but with this physical recession was a soul and a spirit that was still very vibrant.

And in that context and looking at him, I said to him, 'Paul, you've been through an awful lot, 'and you've made some significant sacrifices.

'When you look back at all of it now, 'do you think the journey was worth it 'for the price you've paid?'

He said, 'Harry, let me tell you 'that there's just no question in my mind 'that even with the many victories we've not achieved, 'along with all the victories we achieved, 'one way or the other, the real essence of all of this, 'the essence of life was in fact, or is in fact 'the journey itself, the experiences, 'the men, the women, the children I've met on the way, 'the things that I've heard, 'the lives that I've touched and have been touched by, 'would've made me do this all over again 'and maybe even do it better.

'There's only one thing I wish I knew then that I know now 'that might have made it a little better for me.'

And I said, 'What was that?'

And he said, 'I wish I'd really understood how true it is 'that in the final analysis, 'every generation will have to be responsible for itself.'