How It Feels To Be Free, New American Masters Documentary About Trailblazing Black Female Entertainers Lena Horne, Abbey Lincoln, Diahann Carroll, Nina Simone, Cicely Tyson and Pam Grier

Executive produced by 15-Time Grammy Winner Alicia Keys and produced by Yap Films

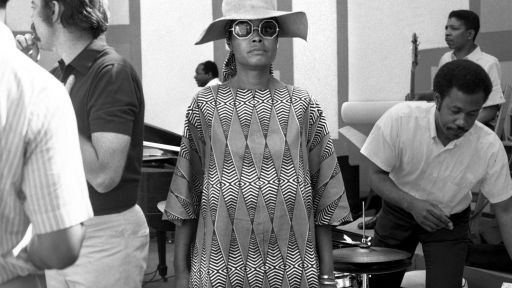

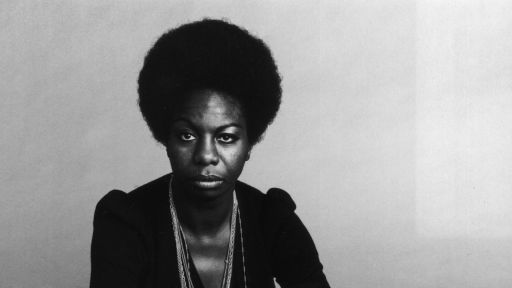

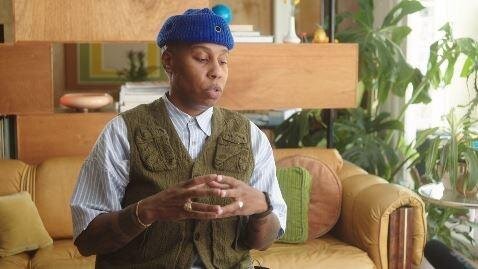

How It Feels To Be Free tells the inspiring story of how six iconic African American female entertainers – Lena Horne, Abbey Lincoln, Nina Simone, Diahann Carroll, Cicely Tyson and Pam Grier – challenged an entertainment industry deeply complicit in perpetuating racist stereotypes, and transformed themselves and their audiences in the process. The film, which is slated to premiere in early 2021 on PBS and on documentary Channel in Canada, features interviews and archival performances with all six women, as well as original conversations with contemporary artists influenced by them, including Alicia Keys, an executive producer on the project, Halle Berry, Lena Waithe, Meagan Good, LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Samuel L. Jackson and other luminaries, as well as family members, including Horne’s daughter Gail Lumet Buckley.

Based on the book “How It Feels To Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement” by Ruth Feldstein, the film tells the story of how these six pioneering women broke through in an entertainment industry hell-bent on keeping them out and situates their activism as precursors to contemporary movements like #TimesUp, #OscarsSoWhite and #BlackLivesMatter. Award-winning director Yoruba Richen (The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, POV: Promised Land, Independent Lens: The New Black) examines the impact these trailblazing entertainers had on reshaping the narrative of Black female identity in Hollywood through their art and political activism while advocating for social change. The film highlights how each woman — singer, dancer and actress Lena Horne; jazz vocalist, songwriter and actress Abbey Lincoln; Tony-winning actress, singer and model Diahann Carroll; jazz, blues and folk singer Nina Simone; actress and model Cicely Tyson; and actress Pam Grier — harnessed their celebrity to advance the civil rights movement.

“These revolutionary Black women embody stories of courage, resilience and heroism. They fought for representation and economic, social and political equality through their artistry and activism,” said Michael Kantor, American Masters series executive producer. “We are proud to share the stories of how each left an indelible mark on our culture and inspired a new generation.”

Director Yoruba Richen said, “At this unprecedented time of racial reckoning and as Hollywood is reassessing its role in perpetuating racist stereotypes, now is the perfect moment to tell the stories of these path-breaking women who have inspired generations of Black female superstars—like Keys, Halle Berry, Issa Rae, Ava DuVernay and Lena Waithe—who continue to push boundaries and reshape how African American women are seen onscreen.”

Executive producer Alicia Keys added, “I am proud to be a part of such a meaningful, important project. Art is the most powerful medium on the planet, and I continue to be inspired by and learn from these powerful, brave and stereotype-shattering women who leveraged their success as artists to fearlessly stand up against racism, sexism, exclusion and harassment. I honor their courage by celebrating their stories and continuing the work they started.”

Harry Gamsu, Vice President of Non-Scripted Content Acquisitions, Fremantle, said, “Throughout the course of history, the stories of Black women have been consistently overlooked and ignored. Now we are witnessing incredible stories like these being told by Black women, and we are honored to be a partner in helping bring these voices to a global audience.”

Launched in 1986 on PBS, American Masters set the standard for documentary film profiles, accruing widespread critical acclaim and earning 28 Emmy Awards — including 10 for Outstanding Non-Fiction Series and five for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special — 14 Peabodys, an Oscar, three Grammys, two Producers Guild Awards and many other honors. To further explore the lives and works of masters past and present, the American Masters website offers streaming video of select films, outtakes, filmmaker interviews, the American Masters Podcast, educational resources and more. The series is a production of THIRTEEN PRODUCTIONS LLC for WNET.

American Masters: How It Feels To Be Free is produced by Yap Films in association with American Masters Pictures, ITVS, Chicken & Egg Pictures and documentary Channel in Canada. Michael Kantor, Alicia Keys, Lacey Schwartz Delgado, Mehret Mandefro, Elliott Halpern and Elizabeth Trojian are executive producers. Yoruba Richen is director. Michael Kantor is executive producer of American Masters. Fremantle holds global distribution rights (ex-US and Canada) to the documentary.