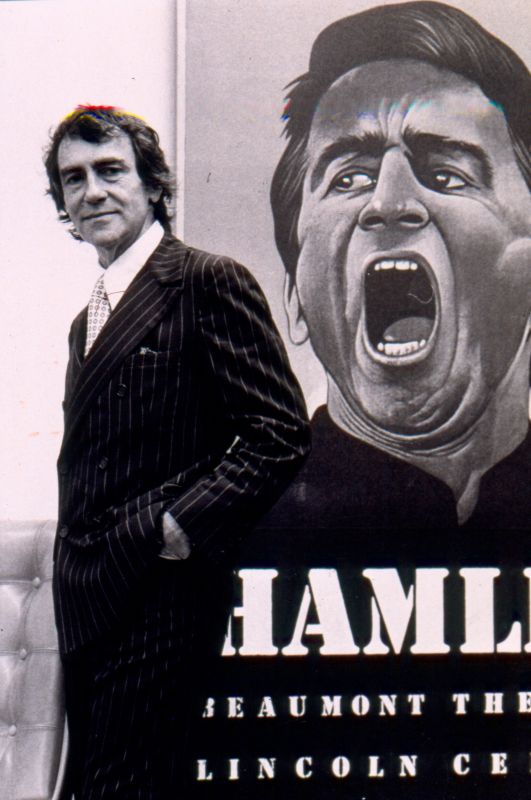

Theater critic David Cote explores the legacy of Joe Papp, the man who brought free Shakespeare to Central Park and nurtured new talent in the American theater.

The visionary and benevolent tyrant

The visionary and benevolent tyrant

Shakespeare would be shocked to learn that 400 years after he’d shuffled off his mortal coil, his plays were being presented in the New World for free. Not even a penny for the groundlings?! The Swan of Avon’s shrewd business mind would boggle at such liberality. Joe Papp’s legacy, you see, fixed Shakespeare as its foundation stone, but reached beyond the Bard—all the way back to ancient Greece. In the years after World War II, Papp was chief architect of an American theater culture that was radically accessible and profoundly civic.

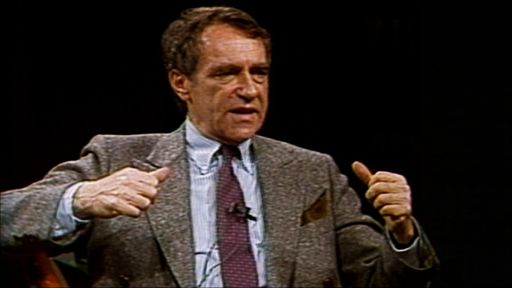

Papp’s storied career—a rags-to-riches arc that spanned several wars and decades of cultural upheaval—rested on (at least) three core principles for which he never stopped fighting. He believed in the inherent civic virtue of noncommercial theater. Second, he stood for the primacy of the producer as visionary and benevolent tyrant. Last, he held up Shakespeare as the gateway to better citizenship and artistry.

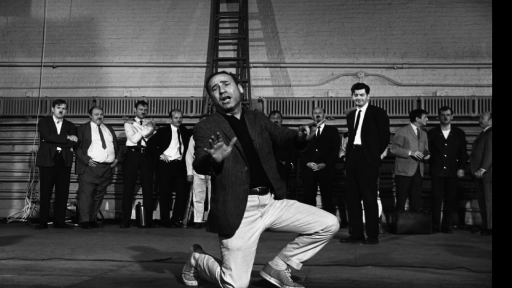

Each of these values guided Papp as he built an empire across four decades, from squatting in a pickup truck in Central Park to carving six Off-Broadway venues out of an abandoned public library, and finally striking gold on Broadway with risky hits such as “HAIR” and “A Chorus Line.” He was an idealist as well as a financial shark. He respected a free press yet frequently harassed critics. Today, Papp would no doubt be a controversial figure—either as Eurocentric apologist or as bullying boss. But his vision of theater for all still earns our “standing O.”

“I am interested in a popular theater—not a theater for the few.”

–Joe Papp

In 1950s America, Shakespeare was not exactly a marginal figure, but the idea of putting on his plays in a distinctly American style, for free, outdoors, was audacious. It was also a threat to cultural gatekeepers as diverse as Parks Commissioner Robert Moses and the theater critic Walter Kerr. The former deemed Papp a Communist who would bring riff-raff into the Park; the latter thought no serious company could sustain itself without ticket sales. In an open letter to Kerr’s New York Herald Tribune published on March 16, 1958, Papp defended his vision as both fiscally and artistically prudent:

“It would be an act of irresponsibility on my part to subject the organization to the chaotic gambling of show business. … I am trying to build our theater on the bedrock of municipal and civic responsibility—not on the quicksands of showbiz economics. I am interested in a popular theater—not a theater for the few.”

A theater uninvolved in Broadway’s lottery mentality, Papp argued, is one free to innovate and excel. Recall that Papp issued this manifesto before Off-Off Broadway had become a vibrant movement (the year Papp’s letter was published, Caffe Cino on Cornelia Street began presenting work). Even though the New York Shakespeare Festival was coeval with La MaMa and Theatre Genesis, its mission was arguably more radical. Papp’s vision for a free and civic theater was essentially Greek, as neoclassical as the architecture in Washington, D.C.

A theater uninvolved in Broadway’s lottery mentality, Papp argued, is one free to innovate and excel. Recall that Papp issued this manifesto before Off-Off Broadway had become a vibrant movement (the year Papp’s letter was published, Caffe Cino on Cornelia Street began presenting work). Even though the New York Shakespeare Festival was coeval with La MaMa and Theatre Genesis, its mission was arguably more radical. Papp’s vision for a free and civic theater was essentially Greek, as neoclassical as the architecture in Washington, D.C.

Theater and democracy have shared the global stage for millennia. From about the sixth century BCE, Athens would hold the City Dionysia festival in the spring, during which Athenians from all walks of life could see great, elevating tragedies by Aeschylus and Sophocles or biting satires by Aristophanes and his peers. In the early days admission was free, but eventually the entrance fee became two obols. (It’s still free at the Delacorte. Sorry, Euripides!) Attending tragedies and comedies was not viewed as an idle pastime; it was the duty of citizens to hear how their great poets translated society back to them.

Papp believed everyone had a right to Shakespeare in Central Park

He conceived of theater as a public utility, like tap water, city parks, or the library. In that sense, he resembles the early evangelists for the Internet, who predicted that the information superhighway would usher in a great new age of educated citizens and transparent authority. Let’s agree that Shakespeare in the Park is doing better at improving society.

“Why Shakespeare?” Papp himself asked in “Free for All,” the oral history about Shakespeare in the Park and the Public Theater compiled by Kenneth Turan. “In terms of theater, he is a master, there is no greater writer for the stage in the English language, and that happens to be a fact. You can’t be an educated person unless you have more than a passing familiarity with the works of William Shakespeare.”

Theater cultures are historically intertwined with national identity. England’s National Theatre shaped postwar British playwriting; in Japan, centuries-old theatrical forms such as Noh and Kabuki are maintained as a matter of national pride. And in America, birthplace of jazz, vaudeville, and the Broadway musical? By the mid-20th century, Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams had emerged as our native dramatists, but we still derive a great deal of our theatrical energy and inspiration from Shakespeare. He was, for better or worse, the go-to dramatist for generations of American actor-managers in the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Democracy in the theater is ridiculous. I don’t believe in it.”

–Joe Papp

(T-B) Actors Christopher Walken as Iago and Raul Julia as Othello in a scene from the NY Shakespeare Central Park production of the play “Othello.”

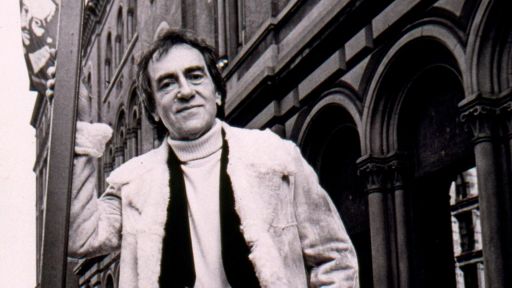

You could say that Papp was the last of the great American actor-managers. Although not an actor, he carried himself like one: proud, pugnacious, painfully alert to how he was represented in the press. He led a troupe of players inspired, cowed and awed by his bravery. They followed Papp wherever he went, even to Central Park when the place was dangerous and untamed and the stage was a pickup truck. He led them to the dusty interior of an abandoned public library on Lafayette Street and saw venues. He was the people’s producer.

And he was tough. Elsewhere in “Free for All,” Papp recalls the dissolution of the first theater group he was part of, the Actors’ Lab in Los Angeles: “[W]hat killed the Lab was the lack of strong leadership,” Papp says:

“Although there are some theaters that operate on this principle, democracy in the theater is ridiculous. I don’t believe in it. Imagine you’re in a military situation, the enemy is firing at you, and every time you want to do something you have to say, ‘Let’s have a meeting.’ … Someone has to be in a position to make a decision.”

Joe Papp’s model endures to this day. The Public Theater still presents free Shakespeare every summer at the Delacorte, and a full season of work on Lafayette Street. It still serves as an incubator for Broadway hits, most recently with “Hamilton.” Today, New York City is full of robust, nonprofit troupes that would not have existed without Papp’s example.

And yet, one has to ask: Would Papp thrive today? Would his browbeating of colleagues and tendency to abruptly fire staff be condemned as a workplace corrupted by toxic masculinity? Even though Papp was a pioneer in colorblind casting, his insistence on dead, white Shakespeare as cultural apex is wide open to criticism. Would his politics be thought too extreme? Not extreme enough? Looking at his life and work, one thing is abundantly clear: There is no drama without conflict, and Joe Papp loved a fight.