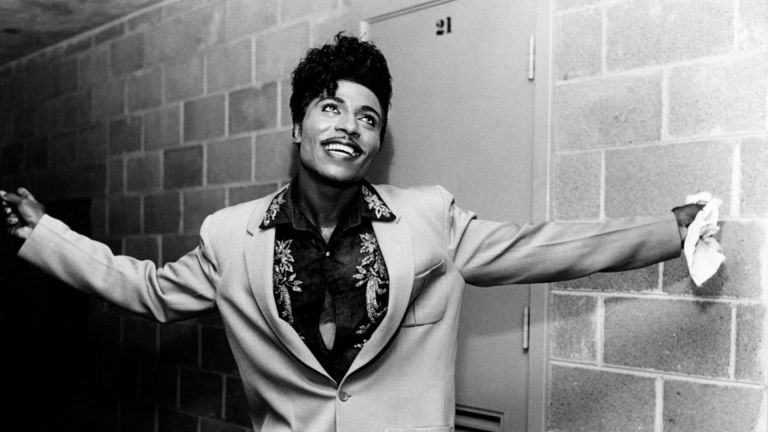

When Little Richard stepped onto the stage of the Radio City Music Hall on March 2, 1988, he came with something to prove.

He had been tapped to co-present the award for Best New Artist at the 30th Annual Grammy Awards in New York City. That evening, he took the stage with Buster Poindexter, the alter-ego of New York Dolls lead singer David Johansen. As a lifelong Little Richard fan, Johansen was excited to co-present with one of his idols. That excitement waned as Little Richard addresses him and the audience. Pointing to Johansen’s towering pompadour, he reminds the crowd, “I used to wear my hair like that.” The playful moment quickly turns into a protest: “They take everything I get. They take it from me.”

Johansen responds with a half-hearted attempt at Little Richard’s famous whoop, immortalized in 1950s songs like “Tutti Frutti,” but the elder performer dismisses the imitation: “He can’t get that, though.” Johansen recalled decades later, “I was really excited, and then he kind of went crazy on television. He was telling me to shut up.”

But Little Richard was on a mission. He wanted everyone to know that he had not received proper credit for his influence on rhythm and blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

Born Richard Wayne Penniman on December 5, 1932 in Macon, Georgia, Little Richard left school to play music in medicine shows and perform in drag in vaudevillian theater troupes.

After making some records with RCA Victor and Peacock Records in the early 1950s, he scored his first hit with “Tutti Frutti” on Specialty Records in 1955. A string of hits followed in the next year, and in 1957, Specialty released his first album, “Here’s Little Richard.” Yet he watched Pat Boone’s covers of his records chart higher than his originals. He saw Elvis Presley crowned the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll. By the time he appeared at the 1988 Grammys, the 54-year-old veteran wanted the Recording Academy and the American public to recognize his role in shaping modern music.

After opening the envelope containing the winner’s name, he proclaims, “And the best new artist is . . . me.”

He continues as the audience laughs, “I have never received nothing—y’all never gave me no Grammys, and I’ve been singing for years! I am the architect of rock ‘n’ roll!” As the crowd leaps to its feet, he finishes like a Georgia preacher reaching the climax of a sermon. “And I am the originator!” He then lets out a whoop to show us how it was supposed to be done.

I was only 12 years old when Little Richard made his headline-grabbing statement at the Grammys, but I was already a fan. My grandfather, noticing my burgeoning love for music, gave me a Little Richard greatest hits compilation when I was in second or third grade. I was enthralled by the voice that spilled from my cassette player. The music was energetic, hard-driving and oozing with youthful exuberance. Although Little Richard had recorded songs like “Rip It Up” and “Lucille” thirty years earlier, I enjoyed his music alongside my 80s favorites like Janet Jackson, New Edition and Prince. So, I paid attention when he appeared on television. And he seemed to be everywhere—award shows, commercials and late-night TV.

In the 1980s, Little Richard had embarked on a new kind of tour, one designed to secure his legacy.

He spent much of the decade reminding the world of how much he had influenced the pop culture landscape we inhabited. He even managed to honor himself while celebrating his peers in the industry. While posthumously inducting Otis Redding into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1989, he pointed to other icons who had toured with him over the years—Jimi Hendrix, The Beatles and Mick Jagger.

Little Richard also noted his influence on artists who reveled in gender nonconformity, something that had made him threatening in the early years of the Cold War. He frequently mentioned his sexuality, claiming to be “one of the first gay people to come out” during an interview with David Letterman in 1982. And in Charles White’s 1984 authorized biography, “The Life and Times of Little Richard,” he openly discussed sexual encounters with men. Yet he struggled to reconcile his sexuality with his Christian religious convictions. By the 80s, he had once again left the rock world for the church, and he repeatedly told interviewers that he was no longer gay. As he explained to Richard Harrington in a 1984 Washington Post interview, “you cannot be gay in my church.” But as “the first androgynous superstar,” as Harrington described him, he had paved the way for the next generation of gender-bending performers.

“Michael [Jackson], David Bowie, Boy George, they’ve got my spot now,” he proudly proclaimed.

Little Richard also fought for financial retribution in the 1980s.

While his music had made him a household name, he had not earned much money from those records. Art Rupe, owner of Specialty Records, reportedly bought the rights to “Tutti Frutti” for $50 and Little Richard signed a contract that gave him half a cent per record sold.

“I was a dumb Black kid and my mama had 12 kids and my daddy was dead,” he explained. “I wanted to help them, so I took whatever was offered. Rock ‘n’ roll was an exit for me.”

In 1984, he sued three record companies, including Specialty, saying he had not received royalties since 1955. He settled for an undisclosed amount.

As his speech at the 1988 Grammys indicated, though, the industry owed him more than money.

He also wanted the recognition. The Recording Academy finally honored him with a Grammy in 1993 when he won a Lifetime Achievement Award. He was also one of the first class of Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees in 1986, and he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003.

Little Richard was always convinced of his own greatness. And by the time he died on May 9, 2020, the rest of the world had acknowledged it, too.