Madonna—celebrating her 65th birthday with a victory lap of a tour this year—has been an enormous pop icon for so long that it’s sometimes difficult to remember that there was a time before.

But that time before offers some illuminating insight into the Queen of Pop—particularly her time in New York City on the cusp of stardom as she sought to find her voice and footing as an artist.

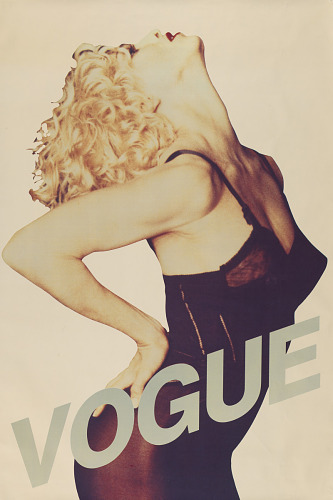

Madonna, 1983 by Kate Simon. Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

A 19-year-old Madonna arrived in New York in 1978 having dropped out of college in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she’d left a dance scholarship to pursue real-world work experience in the field. She got a six-week work-study scholarship at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, took classes at the Martha Graham School and apprenticed with renowned choreographer Pearl Lang. These were rare opportunities, and her teachers saw immense potential and talent in her. But the wild child chafed at the strict, formal rules of the world of prestigious professional dance, and her interests began to shift to stage and film, then to music.1

Madonna had an apt musical teacher in her boyfriend Dan Gilroy, who she met in the spring of 1979. Gilroy and his brother Ed performed together as the Acme Band with a music-satire act called the Bil and Gil Show, living out in Flushing Meadows, Queens, in a building that had once been a synagogue. There, they had a home studio and practice space. Gilroy taught Madonna the rudiments of drumming—a natural leap for a dancer used to eight-counts and open chords on the guitar.2 Her connection with Gilroy would also lead to her first big break—and her first instructive experience in how she didn’t want her career to go.

Belgian producers Jan Vanloo and Jean-Claude Pellerin had “caught a performance of Dan and Ed’s Voideville show at Theater for the New City on Second Avenue,” biographer Mary Gabriel writes. Vanloo and Pellerin were in town holding open auditions for backup dancers to tour with French disco singer Patrick Hernandez, whose “Born to Be Alive” had just gone global. Gilroy tipped off Madonna, who tried out and caught the Belgians’ eyes immediately; they offered to bring her to Paris to develop her as a pop star. (Even as a teenager, the shrewd young businesswoman had a lawyer get involved before she signed anything.) Vanloo and Pellerin took her from the hardscrabble life of a young artist to a world of incredible wealth.

Belgian producers Jan Vanloo and Jean-Claude Pellerin had “caught a performance of Dan and Ed’s Voideville show at Theater for the New City on Second Avenue,” biographer Mary Gabriel writes. Vanloo and Pellerin were in town holding open auditions for backup dancers to tour with French disco singer Patrick Hernandez, whose “Born to Be Alive” had just gone global. Gilroy tipped off Madonna, who tried out and caught the Belgians’ eyes immediately; they offered to bring her to Paris to develop her as a pop star. (Even as a teenager, the shrewd young businesswoman had a lawyer get involved before she signed anything.) Vanloo and Pellerin took her from the hardscrabble life of a young artist to a world of incredible wealth.

She was given a vocal coach (though Gabriel notes that she “only met with him a few times” because she disliked him), dance lessons, and an introduction to the international elite. But she was stifled by the lack of creativity. She didn’t want the pre-written songs offered to her; she wanted complete control of her art and work. When Gilroy asked her to return to New York, she claimed she wanted to return to the U.S. for a vacation, getting Vanloo and Pellerin to pay for a round-trip ticket on the Concorde. “She left her clothes in Paris, as if she planned to return. She did not,” writes Gabriel.

Returning home, Madonna resumed her musical training with Gilroy and picked up the drums in Acme Band when their drummer, Mike Monahan, quit. By that time, they’d been getting gigs at hot spots around town like CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City. Eventually, hanging out at the old synagogue with that group of musicians and friends led to the formation of a new band—Gilroy, Ed Gilroy, and their friends Angie Smit, Gary Burke and Madonna became The Breakfast Club, named for their jaunts to the Flushing Meadows IHOP after studio sessions together.

And though Madonna was behind the drums, she yearned to sing, to occupy the limelight. She tried on a range of vocal styles, patterning herself after women she admired—Ricki Lee Jones, Patti Smith, Chrissie Hynde. When Monahan returned, she was able to switch to keyboards. And she was writing her own songs on guitar too. Her overwhelming desire to be the star of the show was ultimately what would lead to its breakup, at least in that form; it had already been causing tension in the band. When she asked to be the lead singer, the Gilroys refused.

She left the group, wanting to start her own band—and that’s when her friend Stephen Bray—who would go on to write many of her biggest 80s hits with her—returned to her life. They’d dated back in Michigan, and he’d gone on to study at Berklee College of Music. Neither of them having anywhere to live, they moved into the Music Building, a rehearsal space in Manhattan still operational to this day. They jammed all day, writing and experimenting. For a while, Madonna played with twins Dan and Josh Braun, who Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore notes were two of the first members of Swans, in a no wave band called Spinal Root Gang.

Bray and Madonna’s songwriting solidified into a band called Emmy—sometimes Emmy & the Emmys—with Madonna taking lead and Bray and Burke with a rotating cast of players backing her up. In an interview with Vinyl Maniac cited in Gabriel’s book, Madonna described their sound as “deranged punk with minimal funk,” which is accurate enough.

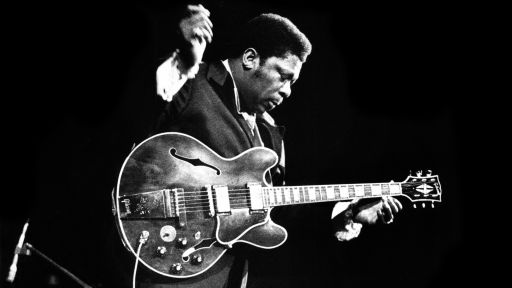

Madonna, 1985 by Francesco Scavullo. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Time magazine.

But while she worked hard at developing an intense rock persona, including working with manager Camille Barbone of Gotham Sound to craft an image, Barbone was steering Madonna towards a more pop-rock style—away from the more avant-garde world she’d been steeped in. Though pop is where she would break through, that partnership blew up in 1982 due to differing visions. Barbone does not remember it favorably: “I risked my own career on Madonna and she nearly destroyed me,” she told writer Christopher Andersen in 1991 for “Madonna: The Unauthorized Biography.” “But I don’t hate her—I miss her.”

Back to square one, Madonna and Bray began making tapes on their own and bringing them directly to DJs. Boundary-breakers like Larry Levan at Paradise Garage, Kool Lady Blue at the Roxy and Mark Kamins at Danceteria were the new tastemakers of the downtown scene now that punk was waning; the new sound blended electro, disco, hip-hop, R&B and Puerto Rican rhythms for a style that felt positively futuristic at the time. Madonna had always felt comfortable in gay clubs going back to her youth; her first dance teacher and mentor, Christopher Flynn, had brought her out with him as a teenager and watched her take over the floor, reveling in the feeling of freedom. On the post-Stonewall club scene, she flourished. You could be untamed; you could be freaky; you could be yourself. And you could dance. (For inspiration, as she would famously exhort at the beginning of “Into the Groove.”)

Over the next couple of years, she would attract a crew of friends who, along with Bray, would shape the image with which she would burst into public consciousness—actor Debi Mazar; dancer and choreographer Erika Belle; artist and club kid Martin Burgoyne; designer Maripol (who worked at Fiorucci and designed Madonna’s iconic early looks); artist and hip-hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy. (The infamous “Boy Toy” belt worn in the Like A Virgin era was actually a nod to her graffiti tag of the same name.) She dated Jean-Paul Basquiat for a bit and befriended Keith Haring.

And this is where she stood in 1982, on the precipice of fame—about to release “Everybody,” surrounded by like-minded vibrant young artists, bright and brash and raring to go.

It’s remarkable how similar her story is to so many artists who never achieve even a scrap of her stratospheric fame—one can feel the genuine desire to Make Something that Matters thrumming through this era. Yes, there’s the clear vision of stardom. But not just any road to fame would do. It had to feel right to Madonna on her own terms. It had to be her art, her way. And, through massive hits and critical pans, that is one of the things that continues to set her apart.

1This time is beautifully chronicled in Mary Gabriel’s 2023 biography Madonna: A Rebel Life, from which much of the information here is derived.

2He notes in the documentary Madonna + The Breakfast Club