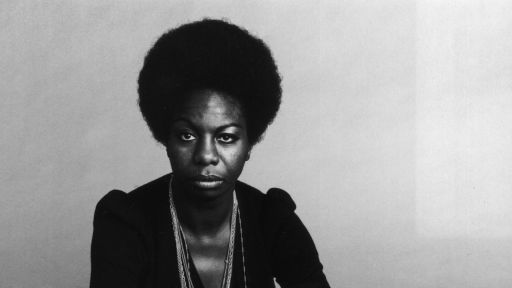

Eunice Kathleen Waymon was not a singer. Her stage persona, Nina Simone, was. Born on February 21, 1933 in Tryon, North Carolina, the young and gifted Eunice was interested only in becoming a classical concert pianist. But through a series of twists and turns that took the budding musician to music schools and eventually clubs around Philadelphia, Atlantic City and New York City, she was compelled to reinvent herself, her music, and message throughout a storied career that spanned nearly 50 years.

Simone was recognized as a musical genius almost from birth. At just six months, her mother realized that her toddler could recognize musical notes on paper, and “it scared her,” Simone said. By the age of three, Simone was already playing complete songs on the piano — blues and gospel tunes at church. But it was really the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and other classical composers that captured the young pianist’s imagination as she began her formal piano lessons.

In 1950, Simone began studying at New York’s famed Juilliard music school and a year later auditioned for a scholarship to attend Philadelphia’s prestigious Curtis Institute of Music. She was rejected. Simone maintained it was racism pure and simple. “I knew I was good enough, but they turned me down. And it took me about six months to realize it was because I was Black. I never really got over that jolt of racism at the time,” Simone relayed in the documentary, “What Happened, Miss Simone?”

The truth of this matter is less certain. In fact, Curtis had accepted Black students to the piano department before 1951, including an 11-year-old prodigy, Blanche Burton-Lyles, who was recommended for early admission in 1944 and 10 years later became the first Black female pianist to graduate, according to the Institute. Nevertheless, the rejection crushed Simone, who vowed to re-audition and started teaching piano while taking her own piano lessons in Philadelphia.

It was an interaction with one of her students that altered Simone’s path forever. That student had a summer gig playing piano in Atlantic City that paid $90 a week. “90 dollars was double what I earned,” Simone later wrote in her autobiography, “I Put a Spell on You,” and so she ended up in Atlantic City in the summer of 1954, “figuring if one of my students could get a job as a pianist, so could I.”

Simone took the leap from classical to jazz and popular music when she began playing at Atlantic City’s Midtown Bar and Grill. There were two issues she had to face head-on at that club that were the catalysts for her first major reinvention. Number one was how to keep from Simone’s strict and religious mother the fact her daughter was performing in a “seedy little bar where old guys go to huddle over a drink and fall asleep”?

“To her that wouldn’t be any different from working in the fires of hell,” Simone wrote.

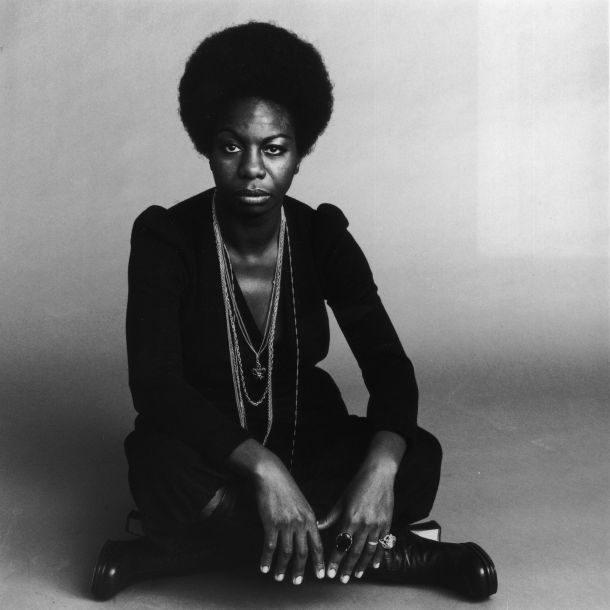

That was the moment Eunice Waymon became Nina Simone — a cloak that would help keep the pianist’s moon-lighting activities under wraps from her mother. The stage name itself was a tribute to the French actress Simone Signoret.

The second issue came later when the bar owner told Simone that in order to keep the gig, she’d have to start singing, too. Just a few years later, Simone’s soulful voice would become known across America with the release of her breakthrough hit — a rendition of George and Ira Gershwin’s “I Loves You Porgy” in 1958. The song was later featured on her debut album, “Little Girl Blue,” and was followed by more recordings, performances at major concerts and festivals, and TV appearances.

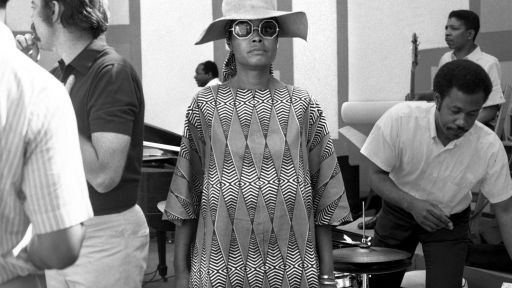

It seemed that Simone had successfully reinvented herself as a jazz singer, although never forgot her classical roots. In numerous performances of jazz standards such as these versions of “All We Know” and “Love Me or Leave Me,” a strong Bach influence can clearly be heard in Simone’s improvisations.

In the early ’60s, Simone’s career took another turn when her music took on a distinctly political tone. Up to that point, she had actively shied away from politics, preferring mostly love songs.

“Nightclubs were dirty, making records was dirty, popular music was dirty and to mix all that with politics seemed senseless and demeaning,” wrote Simone, who also “didn’t like ‘protest music’ because a lot of it was so simple and unimaginative it stripped the dignity away from the people it was trying to celebrate.”

The 1963 bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama changed all that. That racially motivated hate crime killed four young Black girls and lit a fire in Simone. In response, she wrote the song “Mississippi Goddam” to fight back against white supremacy in the only way she knew how.

After her first foray into resistance music, Simone continued to write and perform many more well-known protest songs that invoked elements of jazz, blues, folk, soul, gospel and Afrobeat. These included the tunes “Old Jim Crow,” “Backlash Blues” and “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.”

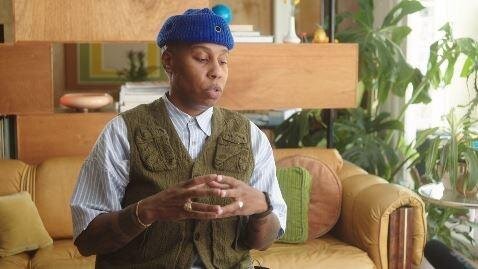

“She’s making such a clear indictment of American racism,” said the activist, scholar and writer Salamishah Tillet. “And she’s doing it through really, really different kinds of musical tradition. She’s coming up with the show tune of ‘Mississippi Goddam.’ She’s using a kind of gospel sound with ‘To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.'”

“I stopped singing love songs and started singing protest songs because protest songs were needed,” Simone famously said. “You can be a complete politician through music. I have become more militant because the time is right.”

Simone continued to write and play a range of music of different influences throughout her career, cementing her status as a ground-breaking and multi-genre performer around the world. She used her talents to speak up for the civil rights movement. Her career reinventions forged a path between classical, jazz and blues, resistance music and beyond, becoming part of the story and evolution of modern American music itself.

“Every song that I sing is important, that it communicates something to someone. It is not just a song. It’s something that says something to someone,” said Simone. “It’s very much like poetry, or like a good play. Something that communicates and gets into the soul of people.”