It was 1929, and Hollywood was facing a conundrum that it had not anticipated, or adequately prepared for.

Sound had rolled in two years prior, with “The Jazz Singer,” and practically overnight, a style of filmmaking that the studios had mastered laboriously over decades was now antiquated.

If you’ve ever seen the movie “Singin’ in the Rain,” with the faulty microphones planted inside shrubs and rustling noisily against costumes and the glamorous silent star played by Jean Hagen revealing an unexpected voice, you might get the picture, if in slightly exaggerated form.

The comedic giants of the silent era wrestled mightily with the advent of sound. Buster Keaton’s career tragically foundered on the rocks of dialogue, and Charlie Chaplin—then the most famous performer in the world—simply chose to ignore the arrival of sound, mostly, releasing two more dialogue-free features (1931’s “City Lights” and 1936’s “Modern Times”) before finally giving in to the inevitable. Screen comedy had been predicated on action and gesture. Chaplin could convey overwhelming feeling in the hunch of his shoulders, or the twirl of his cane. But now performers needed to talk, and be funny, too, and Hollywood did not have the slightest clue how to do that.

Enter Julius, Leonard and Adolph Marx, or as you might know them, Groucho, Chico and Harpo.

The Marx Brothers (usually a trio, although occasionally joined by their brothers Zeppo and Gummo) had been thrust onto the stage as children by their mother, Minnie. Minnie believed her sons had the potential to make a name for themselves—as singers. They began as a group called the 3 Nightingales (soon to become the 4 Nightingales) whose musical numbers were interspersed with rapid-fire patter.

The singing was iffy at best. Harpo was so poor a performer that his mother told him to simply open his mouth when his brothers were singing. Legend has it that a performance in Nacogdoches, Texas was interrupted by a mule that ascended the stage mid-routine, inspiring some hasty banter and causing the 4 Nightingales to give up entirely on singing and reorient themselves as a comedy troupe.

Vaudeville leaned on the expert deployment of familiar stereotypes, and each Marx brother adopted a recognizable ethnic persona. Groucho played German—a familiar comic routine in the years before the U.S. entry into the First World War—and Chico was faux-Italian. Surrounded on all sides by these hyper-verbal masters of the double entendre and the malapropism, the vaguely Irish Harpo, clad in a curly red-haired wig, went silent, letting his horn and his harp (after which he was nicknamed) do the talking for him. The Marx Brothers were themselves Jewish, and part of the joke in adapting these hoary signifiers of ethnic humor was that everyone knew they were no such thing.

“Well, what do you think I am, one of the early settlers?” Groucho would later wonder in 1929’s “The Cocoanuts.”

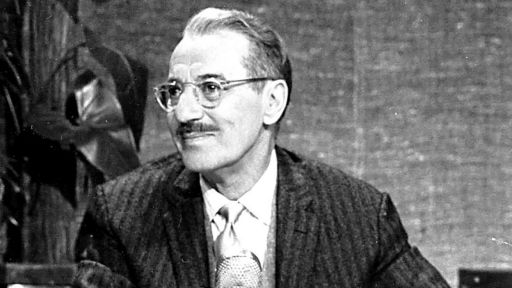

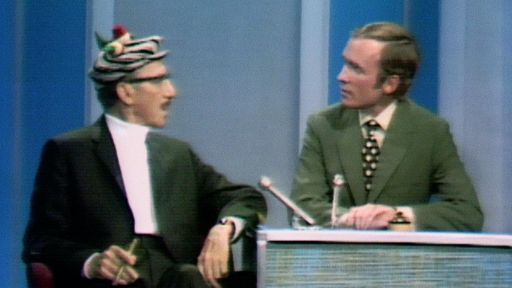

We don’t see The Marx Brothers onscreen until they are middle-aged men.

Chico was 42 when they made their first sound film, Harpo was 41 and Groucho 39. (One silent Marx Brothers film, 1921’s “Humor Risk,” has been lost.) Even in their very first films, we can glimpse the lines on Groucho’s face, testament to half a lifetime spent on vaudeville stages before ever appearing in front of a camera. In this, they share a moment with W.C. Fields and Mae West, similarly recruited from the theater, no longer young but with skills suddenly in hot demand in Hollywood.

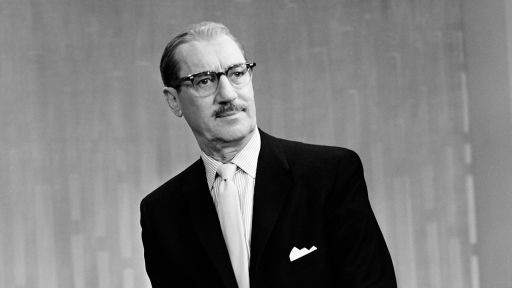

The Marx Brothers arrived with perfectly crafted characters, honed over the course of thousands of nights in front of paying audiences, and their movies are inspired bits of nonsense, designed to tear down all manner of clay-footed idols. Groucho was a silver-tongued incompetent posing as a paragon of society, hoodwinking a straight world represented by stiff-necked Margaret Dumont. He was an African explorer, a university president, a political leader, forever tickled that no one had yet discovered his inaptitude for all manner of authority.

“Hooray for Captain Spaulding, the African explorer!” rang out one musical number in 1930’s “Animal Crackers,” and Groucho responds, concerned: “Did someone call me schnorrer?”

Groucho was indeed a schnorrer, a beggar perpetually in search of recognition from an elite that could never keep up with him. “Your eyes,” he woos Dumont in “The Cocoanuts.” “They shine like the pants of my blue serge suit.” You could take the boy out of the shmatte district,1 but you could not take the shmatte district out of the boy.

The studios, mostly founded by Eastern European Jewish immigrants whose hold on the upper rungs of American society was tenuous, did not much like the idea of explicitly Jewish humor in their movies, and this, too, was folded into The Marx Brothers’ jokes. “All along the river, those are all levees,” Groucho shows Chico, seeking to sell him a piece of Florida real estate in their first film, “The Cocoanuts.” “That’s the Jewish neighborhood?” Chico inquires.

The silent comedy was rooted in its free-floating anarchy, its desire that all manner of pomp and fluff be torn to shreds by the uncontrollable democracy of comedy. The Marx Brothers were like a spoken-word update to the model, with their relentless gusher of petty combat, romantic intrigue, delirious haiku and social satire leaving audiences breathless in an effort to simply keep up.

The Marx Brothers provided the precise thing that Hollywood needed, in these earliest days of sound.

Groucho brought the surreal into the workaday environs of the movie studios, finding humor in twisting and bending a joke until it took on a radically unfamiliar shape. He invites his brothers in for a job interview in their masterpiece, 1933’s “Duck Soup,” and confronts them with a question:

“Now what is it that has four pairs of pants, lives in Philadelphia, and it never rains but it pours?”

“Duck Soup” is the best thing The Marx Brothers ever did, and one of the very best movies ever produced by the studios in their heyday. It is anarchic, savage, unstinting in its satire of combat both political and martial. It is also an unbroken chain of absurdities, culminating in the glorious physical comedy of Harpo posing as Groucho’s mirror image, with the suspicious Groucho testing him by skipping, pogoing, jitterbugging and lifting his arms in praise to the heavens.

Their movies were fast, and no one was faster than Groucho, who gave off the impression of issuing this tidal wave of quips on the spur of the moment. Contemporary audiences may struggle to keep up with the titanic rush of dialogue, pouring out in streams of free-flowing absurdity. Groucho’s monologues often wind up somewhere radically different from where they started, only following the warp and weave of his dazzling comic mind.

“You know who sneaked into my stateroom at three o’clock this morning?” he asks a ship steward in “Monkey Business.” “Nobody! And that’s my complaint. I’m young—I want laughter, gaiety, ha cha cha.”

Groucho is present as master of ceremonies, statesman manque and elder sibling in a never-ending series of battles large and small. For Groucho, talk was all there ever was, and it was more than enough.

1 Editor’s Note: Shmatte means rag in Yiddish. Shmatte districts refer to garment districts often in urban Jewish ghettos.