Marian Anderson looms large in history not only for her achievements in classical music, but also for the strides she made for Black artists in the mid-twentieth century. Since her career took off in the 1930s, she has become a beloved cultural figure and achieved icon status in the realms of music history, civil rights, and—to an extent—fashion. In recent years, Anderson has been celebrated for her sartorial prowess and her gowns exhibited at prominent arts institutions.

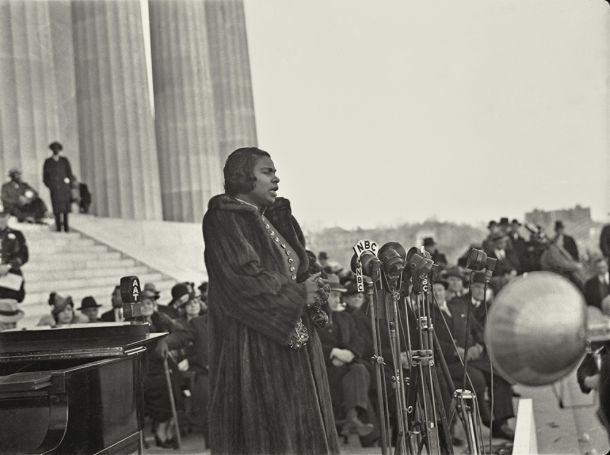

As a performer, Marian Anderson implicitly understood the power of clothes. People flocked to concert halls to hear her melodious voice, but she also recognized that “the first impression on an audience is the visual one.” From the mink coat she wore for her landmark Lincoln Memorial concert in 1939, to the lace gown she wore for a 1955 Carnegie Hall recital, Anderson always appeared well-appointed and the apotheosis of sophistication. As a celebrity songstress, her cultural identity was imbued with a requisite air of glamour. Her illustrious career, which consisted of international travel and audiences with high-ranking members of society, afforded her the lifestyle of a true diva. And yet, as she states in her 1956 memoir, “My Lord, What a Morning: An Autobiography,” “No one needs to tell me that I am not a glamour girl, and I do not try to dress like one.” How then, has she come to be perceived as such?

“Marian Anderson” by Laura Wheeler Waring. Courtesy of Smithsonian.

Looking back on Marian Anderson’s sartorial legacy from a twenty-first century perspective reveals the elegant trappings of a bygone era—one with an elevated sense of formality, especially in the world of the performing arts. True, there is an indisputable sense of refinement in the way Anderson dressed—immortalized in portraits by painter Laura Wheeler Waring and photographer Yousaf Karsh. And yet, the actual garments depicted in these images are relatively understated when compared to the fashions of the period. While Anderson’s performance ensembles generally followed the reigning mode of the time, to her they were more akin to stage costume than actual fashion. She often referred to her wardrobe of concert gowns as her “working uniform”—a component of her job as a classical singer. She confessed in her memoir: “I pay much more attention to my concert costumes than to my everyday clothes. I have threatened at times to spruce up my daily wear, but somehow have not succeeded.”

Throughout her career, Anderson kept record of which gowns were worn at different venues while on tour, so as to not repeat the same gown in any particular locale. She came from humble beginnings, and shopped ready-to-wear from department stores in her early days of performing. Even then, she recalls that she “tried to have clothes that were simple in design but made of good material and effective in appearance.” For her debut performance with the New York Philharmonic in August 1925, she purchased a dress from Wanamaker’s (a department store in her hometown of Philadelphia where her mother worked as a cleaner) that was “very smart without being gaudy.”

As Anderson’s singing career was elevated to new heights, so too was her performance attire. She began working with costume designers like Ladislas Czettel and Raoul DuBois, who designed her tour gowns at the top of each season. These were constructed by Barbara Karinska and other New York-based theatrical costume houses like Eaves Costume Company. One gown in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York dates to 1938 and bears an Eaves label. It is made of gold lamé, and lined in peacock blue silk with iridescent sequins—materials that seem to contradict Anderson’s self-proclaimed preference for “simple, tasteful clothes.” Still, the gown is modestly cut, with long sleeves and a high neckline. The elongated bodice and sweeping train recall the proportions of late-19th century fashionable dress. A similar nod to historicism can be seen in another gown from the MCNY collection—this one of emerald green silk taffeta embellished with black jet embroidery. The pleated fullness in the back of the skirt is reminiscent of the bustle, which was a prominent feature in Victorian-era fashion.

These historical references in Marian Anderson’s concert gowns harken back to the 19th century and the era of the grand opera diva. In those days, leading female vocalists took to the stage in extravagant costumes that fashioned their glamorous personas. Jenny Lind, one of the most highly regarded singers of her time, was so known for her operatic roles that a series of paper dolls were manufactured around 1850 to commemorate her most beloved stage costumes. Italian soprano Adelina Patti enjoyed fame in such a conspicuous manner that she became known for appearing on stage bedecked with precious jewels given to her by wealthy admirers. Her equally fabulous American counterpart, Sissieretta Jones (sometimes called “The Black Patti”), found international success and became the first Black woman to headline a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1892.

It is not a stretch to see why Marian Anderson has been given such close cultural proximity to these women who came before her. And yet, it was the very aspects of her identity as a performer that made her so unique which ultimately prevented her from participating in the grand tradition of opera diva-dom. For one thing, Anderson was primarily a concert artist—not an opera singer. Due to discriminatory practices within the industry, she was barred from the opportunity to sing operatic roles until 1955, when she became the first African American singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera. She played the sorceress Ulrica in Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera,” a part which was not particularly glamorous. Though Anderson had a three octave vocal range, she was billed as a contralto (the lowest female voice type). The flashiest roles were written for sopranos—and therefore, she was excluded from embodying any of the great operatic leading ladies that defined the careers of the divas that came before her. However, Anderson used her lower register to produce a rich tone that expanded her musical repertoire beyond opera. Hers was a voice well-suited to art songs and spirituals, which tend to forgo ornamentation in favor of solemnity.

The same could be said for Marian Anderson’s sartorial sensibility. Throughout her career, she made deliberate choices regarding her appearance that ultimately helped shape her persona as a distinguished trailblazer in the world of classical music. She saw clothing as a necessity of her craft, and always prioritized elegance over glamour—choosing to outfit herself in a manner that was dignified above all else. In her memoir, she demonstrates a keen awareness of her position as a standard-bearer for her race, saying, “I think that my people felt a sense of pride in seeing me dressed well.” And though she insisted that she was “not a dazzler” when it came to matters of dress, her use of performance costume as a tool for social change has proven to be the ultimate fashion statement.