Anne Makepeace, who previously worked with American Masters as writer/producer/director of Robert Capa: In Love and War as well as Edward Curtis: Coming to Light, answers questions about the making-of I.M. Pei: Building China Modern. In this interview she talks about the challenges of filming in China, her creative process when interviewing subjects and documenting a story, and her admiration for Pei’s body of work.

What first got you interested in doing a film on I.M. Pei?

When Eugene Shirley, the producer of I. M. Pei: Building China Modern, contacted me back in 2003 to ask I would be interested in directing a film about Pei, I was very excited about the idea. I had seen Pei’s pyramid at the Louvre and other buildings done by him – CAA in LA, the East Wing of the National Museum of Art – and was eager to find out more about the man behind these great works. Eugene had been directing as well as producing up until that time, but found that producing itself was more than full time, especially in China. I was very happy to be asked to take over that role.

While making the film, did you learn anything that surprised you about Pei?

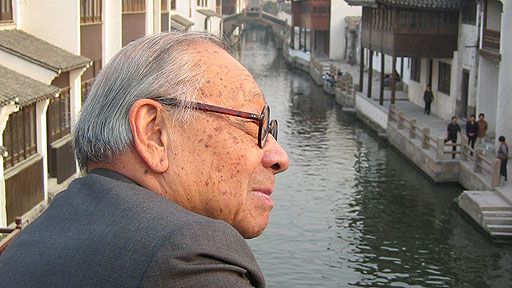

I was amazed at the sheer number and variety of buildings Pei had designed and built. And I found the story of his exile from China very compelling. Pei left China in 1935 at age 17 to study engineering, intending to return home at the end of his studies. For decades his return was interrupted by war and revolution, keeping him in the United States for his whole adult life. Then at the age of 85, he was asked to design an art museum for his hometown city of Suzhou. The story of the “Return of the Native” was very compelling for me.

Are there any interesting anecdotes about the filming or the interviewees?

Suzhou Museum, Night View, I.M. Pei Architect with Pei Partnership Architects. Photo by: Kerun Ip

Filming in China presented huge challenges for the production. We were constantly shadowed by friendly but strict representatives of the Communist Party, including our translators, so we were not able to hear any negative points of view about the museum, which after all was extremely controversial in that it required destroying neighborhoods in an area protected by UNESCO, which had designated that part of Old Suzou as a World Heritage Site. When interviewing officials, we were required to adhere to a very strict list of questions. Filming Pei at the Louvre was a joy, however – he seemed very free and happy to be there, and that shoot provided an opening to the film that enabled audiences to enter into the story of tradition vs. modernism, our focus in China.

Please describe your approach to the film.

During interviews, I like to prepare a list of questions, but then to be spontaneous and open to following interesting threads that I may not have foreseen. I also like to get as much verité footage of everything that is happening around the subject of the film, and then to discover the story in the footage during editing.

What were some of the obstacles in achieving your vision of the film?

This was one of the rare films that I directed but did not produce, and Eugene’s and my visions were not always the same. I was more interested in the biographical and personal aspects of Pei’s life and how these influenced his design of the museum; while Eugene’s focus was very much on the theme of the film – tradition vs modernism – as reflected in the in the creation of the Suzhou museum. In the end, we created a film that we are both very proud of.

Please describe your background credits, how maybe they led to this film.

Eugene contacted me in 2003 after seeing my recently completed documentary, Robert Capa: In Love and War, which I had written, produced and directed for American Masters. Apparently, he liked what he saw there, and I had also been recommended to him by people at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, and elsewhere. The Capa film, as well as my previous film on Edward S. Curtis, which was also broadcast on American Masters, gave him confidence that I could direct a strong film about an artist and his work.