Executive Producer and Producer and Eugene B. Shirley, Jr. talks about the making of his thirteenth film with WNET.ORG, I.M. Pei: Building China Modern. In this interview he discusses how he initially became interested in the work of Pei, the multiple trips to China needed to realize the film, and the unique challenges of long term documentary projects.

What first got you interested in doing a film of I.M. Pei?

The project traces back ten years – when PACEM, the company that I co-own with my sister Anne Shirley, wanted to do a film or series on China’s modern development. The issue we were interested in exploring was the tension between modernity and traditional Chinese culture. Problem was, we had an important theme but no story.

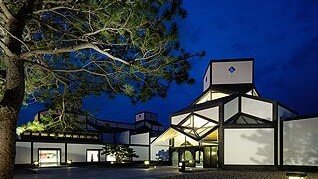

T’ing Pei, I.M. Pei’s eldest son – to whose memory the film is now dedicated – helped us find the story we were looking for in his father’s return to his ancestral home to build a modern museum in the ancient city of Suzhou. T’ing arranged for us to join his father and the rest of the design team on the first site visit in the spring of 2002 – and we followed the story as it unfolded over the next eight years.

The story of I.M. Pei designing and building the Suzhou Museum became the microcosm through which we could view the entire world of our theme.

And the story worked on so many levels – whether it was a matter of architecture, garden design, or Pei’s own personal story, the issue was one of bringing together old and new in way that moved forward without denigrating the past.

When did you first become aware of Pei?

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I tried unsuccessfully to launch a series on postmodernism. The architectural historian Charles Jencks and the philosopher John B. Cobb, Jr. (both of whom play important interpretive roles in the Pei film) were key to that project.

John gave me the tools needed to do a better job of “reading” culture philosophically. Charles helped me interpret architecture – and broadened my awareness of the history of architectural form.

By 2002 when I had the opportunity to make a film with I.M. Pei, I already had a strong interpretive framework in place for using his story to examine some of the cultural tensions between modernity and tradition that I had been so interested in exploring.

While making the film, did you learn anything that surprised you about the subject?

Pei constantly surprised me.

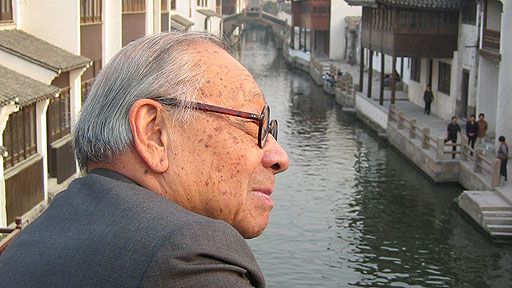

I remember flying 16 hours to meet up with him in China – arriving at approximately the same time he did – only to find our crew, in their 30s, 40s and 50s, running throughout the day to stay up with him, when he was in his late 80s. It seemed he had extraordinary energy. And it seemed to be the case, too, among some of his Chinese contemporaries whom I also had the pleasure to meet – architects and developers.

I remember the first time we were in Suzhou in 2002 – following Mr. Pei was like following after an American rock star. There was the police escort. Tons of photographers and journalists (we were right in there with them, of course). And big crowds. How he could focus in the midst of all those people I’ll never know.

I remember accompanying Mr. Pei to the Four Seasons Hotel/Shanghai one time for lunch, in 2004 or ’05, and by chance a major conference of leading international business leaders was being held there – with bankers, heads of multi-national insurance companies, etc. Of course, no one was expecting Mr. Pei to walk through the lobby because no one knew he was in town. But as we entered the hotel and began to walk toward the restaurant, a receiving line spontaneously sprung up. Every one of the great and good shot to their feet just waiting to shake Mr. Pei’s hand and say a few words. (I know for a fact who these people were because I was standing right next to Mr. Pei and collected their business cards.)

And I was surprised at the way Mr. Pei so boldly took on landscaping the garden areas at the Suzhou Museum – such a difficult challenge, so late in his career, with so many risks. The risks of failure were very real. I think that some of the challenge, and the way Mr. Pei faced the challenges, comes through in the film.

Are there any interesting anecdotes about the filming or the interviewees?

It took something like 17 trips to China to make this project happen. Many trips had to take place at the last minute – and visas secured at a moment’s notice. Nothing like this could have been possible without the strong support of our colleagues and co-producing partners in Beijing.

We were very fortunate that one of our key consultants had had a major position at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing some years back and knew how to connect us in China. He directed us to what he said was the best organization in China to work with on these matters – the China Intercontinental Communication Center, or CICC as they are listed in the credits.

The group is organized under the Ministry of Information, and of course they were careful to make sure that we abided by Chinese law. Sometimes there were tensions, certainly. But the film simply could not have happened without them.

I forged many strong friendships with wonderful people at the CICC over the years who helped us out of tough spots over and over again. Given that we came into the project not knowing the culture, and that we were dealing with high-profile material – that is, Pei returning to China to build this museum – the CICC’s involvement was absolutely essential.

And they stayed with us throughout the course of what became an incredibly long and trying project. We wound up working together for nine full years on this project (including a year prior to when Pei became involved).

Please describe your approach to the film.

I was fundamentally interested in a theme – modernity and tradition – and using Pei’s story to illuminate that theme. So every choice I made was to try to bring this theme into sharp focus.

The first choice was to focus our story about modernity and tradition in China through the lens of I.M. Pei designing and building the Suzhou Museum. This wasn’t easy.

I fought and lost some very tough and expensive battles at the beginning of this project – because not all of my early collaborators on the China-based project I had initially launched wanted to focus on Pei’s story. It’s not that they didn’t appreciate Pei. It’s that they didn’t understand the filmic necessity of focusing a large theme through the lens of a highly specific story – and didn’t see how Pei’s story could do this.

I staked a lot on this choice and ruined some relationships as a result. But I thought that a film about China facing modernity couldn’t do any better than to look at this theme the way I.M. Pei would.

The second big choice was to ask Anne Makepeace to be director. I had directed the film myself for the first two-and-a-half years or so – with my long-time collaborator George Adams serving as Director of Photography. But I felt that the film needed a full-time producer – which I’m pretty good at – and a truly great director – which wasn’t me but it was Anne. Then George and Anne started working together as George stayed on as DP throughout.

The third big choice was to keep the project going when, years in, it had sapped all of our energy and resources and was proving remarkably difficult in ways we never foresaw. The darkest period for this project came after roughly five years.

The film was expensive and taking place half a world away. And every design or construction delay delayed us – in a way that we had no control over.

I made a big mistake thinking that funding a project like this would be relatively easy. It was in fact excruciatingly difficult.

Early on we found wonderful, generous, and unwavering support from our major sponsor the Miho Museum in Japan – and they remained behind us every step of the way. Co-Executive Producer Caroline Courtauld was fabulous and a big help throughout, as were members of our advisory board and board of consultants who played key roles at times. But no one expected the project to go on as long as it did. Or face the sheer number of challenges that a project must face when it goes on year after year after year in a foreign country.

Relationships of various kinds strained – as normal for a project that seemed to go on without end. At one point, Years Six and Seven, we had to augment the team, bring in some new energy, and push ahead. Brian Funck, editor and writer with Anne, was at the vanguard of that new energy

What were some of the obstacles in achieving your vision of the film?

Time. Eight years of production on top of two years of development took its toll.

Distance – our story was happening half a world away.

Money – there’s never enough for documentaries given all that must go into them. Short projects can make do – whatever the financial pain will all be over soon. Long projects are torture.

This begs the question of how the project survived and got completed in the end. In fact, tons of people stepped in at every step along the way – from the woman who loaned us the startup funds in 2002 to the lab that donated its digibeta deck to us in 2010.

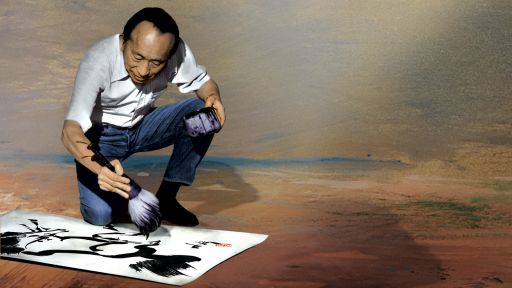

This also says something about Mr. Pei – how everyone wanted to be a part of tipping their hats to him as it were. Artists and craftsmen and businesspeople and scholars of every stripe wanted to do what they could – not for the credit, but to join with others in drawing attention to what he has done and likely just to say thank you.

I’m thinking of that knife-blade edge at the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art that Mr. Pei designed. Four feet up from the ground the limestone is dulled and the color is nearly black from all the people – myself included – who have rubbed the edge.

Perhaps this film became for many, many people another way of rubbing the edge of creativity and design that Pei has bequeathed to us all.

Please describe your background credits, how maybe they led to this film.

This is the thirteenth film I’ve made with WNET – the other twelve as parts of stand-alone series. All dealt with big ideas – and this project is another of the big ideas that I’m passionate about.

I started off my career making films in the Soviet Union, and produced six films there (two stand-alones and one four-part series). Moving on to China seemed almost inevitable.

But whereas in the Soviet Union I was documenting something that was coming to an end, in China I’ve felt I was documenting something much more vital and rising up.

And having tried once to produce a series on postmodernism put me in a position to investigate how China was attempting to bring together modernity and tradition – in the person and work of I.M. Pei.