“There was an old darkey

And his name was Uncle Ned….”

–Little House in the Big Woods

“She did not make one mistake in geography.”

-Little House on the Prairie

By Lizzie Skurnick

We tend to excuse the “Little House” series’ offenses as a product of their times. As a girl, I know I did. The lurid depictions of thieving Indians; the “half-breed” pal Big Jerry; Pa’s exuberant performance in a minstrel show — these images were jarring, and wrong. But they were, I felt, obvious relics of the past.

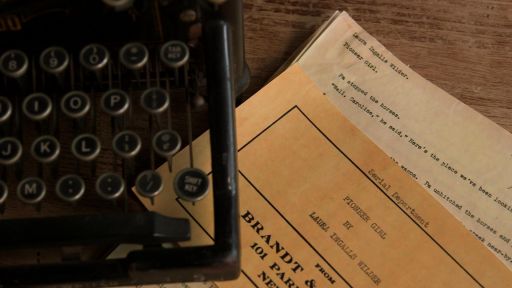

It was only as an adult that I learned the series was not a faithful recollection. Rather, it was Wilder’s fragmented memories, coaxed into a narrative by daughter Rose Wilder Lane. This mother-and-daughter team had a vigorous agenda, excising, embroidering, and inventing events entirely. Which meant that the “savages” and the minstrels were not a product of the 1800s. They were the creation of two adult women living in New Deal America.

And what these women created was one of the most successful campaigns in publishing history: a campaign for the myth of white self-sufficiency. Over the course of nine novels, that myth justifies the taking of land, goods, and power. Its bigotry is not isolated, or incidental. It is the driving force of the narrative.

The extermination of Indigenous citizens and the work of Black citizens were vital to the Ingalls’ enterprise, and Wilder erases them. For the reader who has watched her painstakingly detail how to color a pat of butter and peg a cabin, this inattention to those who sacrificed to make that cabin — this incuriosity — is painful. That I love the books does not make this any less true.

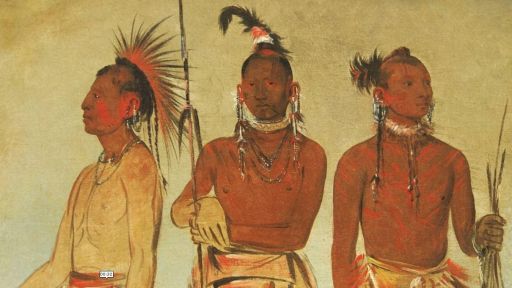

That myth first takes flight in “Little House on the Prairie.” Wilder depicts the family arriving in virgin Kansas territory, but, as the real-life Pa surely knew, the Ingalls were squatters. They had set up camp on the Osage Diminished Reserve, land owned wholly by the Osage and not open to homesteaders.

In Wilder’s novel, the Osage are a troublesome feature of the landscape, not its landowners. Like locusts, they descend on the cabin to strip the family of their goods. Stinking of skunk skins, “dirty and scowling and mean,” they plunder Pa’s tobacco, take all the cornmeal, and nearly make off with an armful of furs.

Only the magisterial Soldat du Chêne, a character drawn mostly from Wilder’s imagination, is, in Pa’s opinion, “no common trash.” At the eleventh hour, the venerable Osage chief convinces a war council bent on massacring the squatters to hold off. (There is little proof any such event took place.) The settlers are saved, and Pa announces, “That’s one good Indian!” unlike their neighbor Mrs. Scott’s remark, “The only good Indian is a dead one.”

Another savior soon swoops in — the very real Dr. Tan. Readers will remember him as the smiling Black man fetched by Jack when the Ingalls are stricken with malaria. In the novel, the doctor cures the Ingalls, then vanishes from the narrative forever.

But the real George A. Tann, known familiarly as Doc Tann, was the Ingalls’ closest neighbor. He lived just across the creek. One of the many Black settlers drawn to Kansas and Indian Territory by the 1862 Homestead Act, he treated all inhabitants of the area — Osage, Cherokee, Black, and white. He was not simply a good Samaritan. He was the family doctor. And in 1870, just in time for the census-taker, he delivered Laura’s younger sister, Baby Carrie.

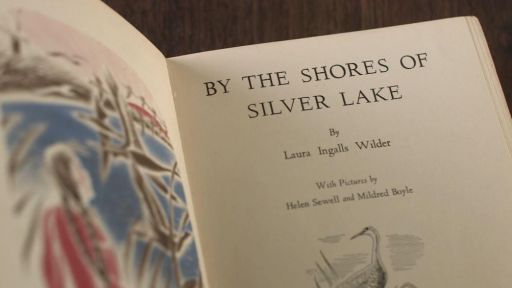

If Tann’s role in the family saga is minimized, the “half-breed” Big Jerry of “By the Shores of Silver Lake” is made mythic. The gambler and rumored horse thief from the railroad camp where Pa works has a soft spot for the Ingalls. He drives off another horse thief. After Pa warns him of an ambush, Jerry ensures no horses are stolen from the Silver Lake camp. And in a final act of valor, he draws off a boisterous crowd bent on ransacking Pa’s store in return for their pay.

There is no record of the real Big Jerry performing any of these feats. Pa was not protected by a kindly American Indian friend. But ironically, the Ingalls were under very real protection — from their despised government. Starting in 1880, the Black soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry were garrisoned in not one but three forts in Dakota Territory: Fort Meade, and Fort Randall, and Fort Hale.

These soldiers were there on behalf of the settlers, and did their work in even more punishing conditions. They protected the railroad crews and telegraph workers from American Indian attacks. They traveled to natural disasters to provide aid. They were called in when settlers became alarmed by the behavior of their American Indian neighbors. In short, they enabled towns like De Smet to exist.

In “Little Town on the Prairie,” the chronicle of Wilder’s De Smet years, the labor of Black soldiers who fought for the Union is invisible. Instead, we meet Pa in blackface in a heartwarming depiction of a minstrel show, where he and the other “darkies” make “everyone weak with excitement and laughing.”

Wilder created that chapter from a show in which Pa did not even take part. That episode was written expressly for the entertainment of American children. This was in 1941, two years after Marian Anderson sang in front of the Lincoln Memorial. A teenage Laura might not have grasped where the offense lay. But the adult Wilder certainly could.

Though the books ended, Doc Tann and the Osage did not march, invisible, into history. Doc Tann became one of the most beloved physicians in Kansas and Indian Territory. When the mineral rights on the land he purchased made him a wealthy man, he opened the region’s first hospital. He is still remembered fondly by his patients’ grandchildren. Though a sign over his grave reads: “Dr. George A. Tann: A Negro Who Doctored the Ingalls for Malaria in 1870,” his life was hardly defined by the episode.

The Osage also did not march off into the sunset. When “Little House on the Prairie” concluded, they were bound for Indian Territory, where the land they purchased turned out to be rich with oil. For a time, the Osage were the wealthiest people per capita in the nation. But this wealth was tainted with tragedy. In a scheme that persisted for decades, hundreds of Osage were married, then murdered, for their oil money.

The Black soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth distinguished themselves in the Indian Wars. They opened the entire West to white settlers — without receiving any of their privileges — then served as the country’s first Park Rangers.

All of this history was available to Wilder, and to Lane. It is a complex history that takes time to unravel, and you can argue it was neither her project nor her point. But for her myth to function, Wilder had to rewrite history into a story in which the Ingalls are neither at fault nor in debt. Rewriting that will be left to her readers.

Lizzie Skurnick is the author of “Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading.” Her latest book is “Pretty Bitches.” She lives in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Bibliography

Bernson, Sara L., and Robert J. Eggers. “Black People in South Dakota History.” South Dakota State Historical Society, 1970.

Charbo, Eileen Miles. A Doctor Fetched by the Family Dog. Springfield, Missouri, Independent Publishing Co., 1984.

Fraser, Caroline. Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Metropolitan Books, 2017.

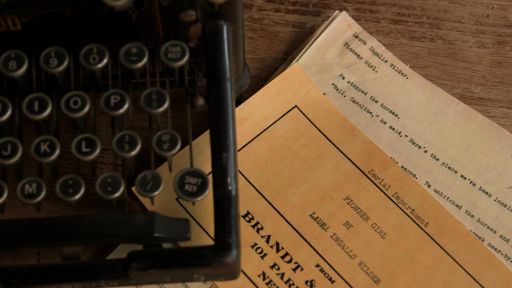

Hill, Pamela Smith, editor. Pioneer Girl. South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2014.

Kaye, Frances W. “Little Squatter on the Osage Diminished Reserve.” Great Plains Quarterly, no. 23, 2000, p. 20. Digital Commons, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/23/.

Linsenmeyer, Penny T. “Kansas Settlers on the Osage Diminished Reserve.” Self Published. Kansas State Historical Society, https://www.kshs.org/publicat/history/2001autumn_linsenmayer.pdf.