TRANSCRIPT

(number beeps) (clapperboard clacks) (horn blaring) (heavy, dramatic music) (chanting in foreign language) - Ask me about the Mauna, and I will tell you about 30 Kanaka huddled, shivering in an empty parking lot, praying that La Hui would answer the call.

I will tell you about two nights, hot sleeping directly under a sky scattered in stars and air so clear, every inhale is medicine.

(horn blaring) How every morning, I woke to ala hui kanaka growing, as if we were watching Maui fish us, one by one, from the sea.

Ask me and I will tell you how on the third morning, I watched as 30 became 100, then 100 became 1,000, then 1,000 became us all.

Ask me and I will sing the song of our manoa hine, linked arms and unafraid, who stood in the face of a promise of sound cannons and mace.

(distant shouting) Ask me and I will tell you that I have been transformed here, but I won't have the words to quite explain.

I will say, 'I don't know exactly who I'll be when this ends, but at the very least, I'll know that this aina did everything it could to feed me.'

And that will be enough to keep me standing.

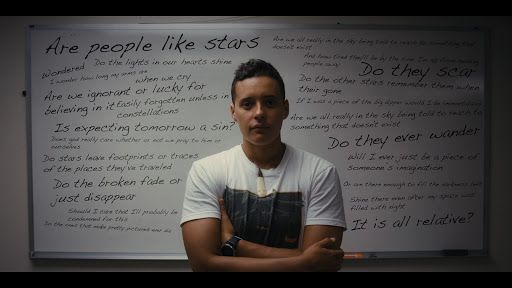

(simple, dramatic music) (flag fluttering) I think about my role as the poet, as having power to make people feel. (marker scribbling) If it doesn't bring a tear to your eye, if it doesn't conjure a memory, if it doesn't give you chicken skin, the poem's useless to me.

(marker scribbling) A poem is as good as it resonates.

And when I find resonance with people, I feel affirmed.

I feel a pilina with them.

Pilina is the word that we use to describe any kind of relatedness, but it also means to be like (claps) stuck to something.

I think we're starving for intimacy, generally.

As Hawaiians, even more so.

There has been this incredible disruption of pilina in ourselves, our land, and the people around us.

(simple dramatic music) (film rolling) Between 1778, when Captain Cook arrived, and the overthrow in 1893, we lost 90% of our population due to disease.

90% of our population just died.

That's an apocalypse. (planes whirring) The world transformed and the ones who lived struggled through this incredible transformation of land and resources and rights and privileges of living on their land.

- We are alive, people, leave!

This is our life!

(overlapping shouting) - Sellouts!

- So there is a history of exploitation that mirrors what's happening on the mountain.

(heavy, ominous music) For the last 10 years, a conglomerate was trying to build a telescope on top Mauna Kea.

This would be the 14th telescope on that mountain, built without the consent of the Hawaiian people.

Mauna Kea, the fight to protect her.

I don't think any of us are anti telescope, but I will say that Hawaiians understand that science that requires desecration is not ethical and it's not science, it's development.

(engine rumbling) - We are not American!

We are not American!

We are not American!

Say it in you heart, say it when you sleep.

We are not American.

We will die as Hawaiians, we will never be Americans!

(crowd cheers) - Raise your hand if before reading for this class, you had never heard of or experienced the wonderful, exciting trauma that is (speaks foreign language). It's a travesty the way that I grew up being taught about poetry because I thought it was the dumbest thing in the world, I thought it was useless.

I thought it was old white dudes meditating on their perfect old white dude life.

So why would that have meaning?

It's not relevant to anything I was experiencing, it couldn't talk to me as a young, queer, Hawaiian woman and helped me understand that I was okay.

Then when I was 16, a friend introduced me to slam.

(light tapping) And a whole new world of poetry opened up for me.

I was hooked.

By the time I was 18, 19, I was writing almost exclusively about Hawai'i, so colonization, the overthrow, annexation, the loss of our language, the loss of a lot of our cultural practices.

For a long time I didn't ever want anyone to read my poetry.

Because I grew up in Hawaiian language immersion school, my concept of my spelling and my grammar is like that (beeps) atrocious, and that used to really bother me 'cause I thought it meant that I was stupid.

So I didn't want people to read the poems.

I just wanted to perform them. (crowd claps) The sea is rising and in my tiny Honolu town, that means underwater homes, there was a wall of water, taunting my homa. (mystical, ominous music) And I was really lucky that got pulled into this slam poetry competition.

Three in life, we come in three stunners.

At the finality of the pattern, one stop, two think.

(gasps dramatically) One stop, two think, three!

(crowd claps and cheers) (dramatic, expectant music) Is there still a way out!? (crowd cheers) The poems were so close to me that I wanted to perform perfectly, not just to win, but to do justice to the poem.

At some point, it became really clear that I could talk about Hawai'i on a microphone.

And if I did it as a poem, people would listen.

Like I could get a lot of people to listen.

What happens to the ones forgotten, the ones who shape my heart from their rib cages?

I wanna taste the tears in their names, trace their souls onto my vocal chords, so that I can feel related again.

But our tongues feel too foreign in our own mouth.

We don't dare speak out loud.

So we can't even pronounce our own parents' names, and who will care to remember mine if I don't teach them?

This is all I have of my family history that's real.

And now, it's yours.

(speaking foreign language) Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio.

Do not forget us, my poena.

(crowd cheers and claps) (cheering drowns out voice) Took 10, 15 minutes to write.

(resonant , ringing music) So the good poems come (snaps) fast.

They just fall out of you.

(pen scribbling) To write from a place of inspiration, it's fast paced, your heart rate shoots up, like there's actual adrenaline involved.

That can feel really invigorating.

I was really lucky to have a lot of those moments that I thought that that's what writing was.

And it made it really hard to have the discipline to keep writing when I didn't have pure inspiration.

I think that's part of the reason I stopped writing and performing. (slow, heavy music) Not only did it become kind of a chore and even a pressure to produce for other people, but I felt like I had run out of things to say and I had run out of new ways to say old things.

People would ask me to perform somewhere and I would wanna say no because I hadn't written a poem in three years.

(horn blaring) - So then, after months and months of waiting, we got the call.

And so our people, we packed up our bags, we stepped away from our jobs because the TMT was gonna start construction, again, on Mauna Kea and we decided that we weren't gonna let them.

So to block the transport of construction equipment, a group of us chained ourselves to the cattle guard on the Mauna Kea access road.

We've been here since about 3:30 this morning, locked in, and they're about to dispatch the police officers to come forcibly remove us. (distant, overlapping chatter) This is an invitation to share this message to come down and bring your mele and your aloha and your kapu aloha to come malama kia aina.

Malama kia aina.

(chanting) - It's already happening, massive civil disobedience, we cannot allow this to happen.

TMT must go away, TMT must leave Hawai'i.

(chanting in support) - My brothers, where's you hearts?

Let them be.

You choose money over us, kanaka ma ole.

How can you do that?

Look what we have to do, you guys make us do this!

Leave them alone, leave them alone.

(sullen, resonant music) (music drowns out voices) - Do a poem. - Do a poem?

Right here?

- Yeah. - Right now.

- Right now?

- Yeah. - Yeah, let's go.

- A poem?

- Yeah. - Drop it, girl.

- I got a long one.

- Yes. - Yeah.

- We got a long time. (overlapping chatter) (surreal acoustic music) - It's 1876 and David Kalakoa, not yet crowned, not yet anointed or kinged pens a song at the request of Kamehameha V.

(speaks foreign language) A new national Anthem, a new symbol of strength, a new promise to the kanaka maui of Kalakoa's generation that like those before, they will stand and fight for the right to noho au puni.

Today, we call this resistance.

- Woo! - Back then, we just called it pono. (heavy, dramatic music) Being there, I had voice again, I had something new to say.

I've written a lot of poems for the mauna this week.

I might just read them.

Ask me about the mauna and I will tell you the mo'olelo of eight kanaka chained to a cattle grate and the kokua that sat beside us.

Aunty says she sees hope in me, and I watch her overflow.

Says she dreamed of this day. (calm, tense music) When you write a poem or a song in Hawaiian, it's no longer yours, you don't have ownership over it.

It belongs to the person you write it to.

That's kinda the beauty in all of this, all the poems I'm writing, they belong to Mauna Kea.

To me, in many ways, they're all just the same poem.

Mauna Kea and are getting to know each other, you know?

It's like falling in love.

This morning, all I have is the magic of a mauna.

Caught in the sight of the sun as we are teased by the treachery of time, all I have is the honesty of this weight.

Weighing minutes stretching across the hardening curve of my spine, all my words caught in the cracks of my breath, hands curling into their own heat.

This morning, I have nothing here to hold you with and you still as constant as the summit with all your magic rising beside me, holding out your hands to catch everything I am, am and not quite yet. (resonant, heartfelt music)

Netflix. Her directorial debut, the feature-length documentary OUT OF STATE, premiered at the 2017 LA Film Festival and later won Best Documentary Feature Film at the Cayman International Film Festival. Recently, Lacy produced a short documentary film about a violinist’s hopes for reconciliation for North and South Korea entitled 9 at 38, which premiered at Tribeca in 2018. Lacy is the inaugural Sundance Institute Merata Mita Fellow as well as part of the inaugural class of NATIVe Fellows at the European Film Market. She has also benefited from fellowships with the Sundance Institute and Time Warner Foundation, Firelight Media’s Documentary Lab, the Sundance Institute’s NativeLab, Tribeca All Access, the Princess Grace Foundation, the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, and the Independent Film Project (IFP). Lacy holds a B.A. from Yale University, and is a lecturer at the University of Hawaii West Oahu in its Academy for Creative Media. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Netflix. Her directorial debut, the feature-length documentary OUT OF STATE, premiered at the 2017 LA Film Festival and later won Best Documentary Feature Film at the Cayman International Film Festival. Recently, Lacy produced a short documentary film about a violinist’s hopes for reconciliation for North and South Korea entitled 9 at 38, which premiered at Tribeca in 2018. Lacy is the inaugural Sundance Institute Merata Mita Fellow as well as part of the inaugural class of NATIVe Fellows at the European Film Market. She has also benefited from fellowships with the Sundance Institute and Time Warner Foundation, Firelight Media’s Documentary Lab, the Sundance Institute’s NativeLab, Tribeca All Access, the Princess Grace Foundation, the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, and the Independent Film Project (IFP). Lacy holds a B.A. from Yale University, and is a lecturer at the University of Hawaii West Oahu in its Academy for Creative Media. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.